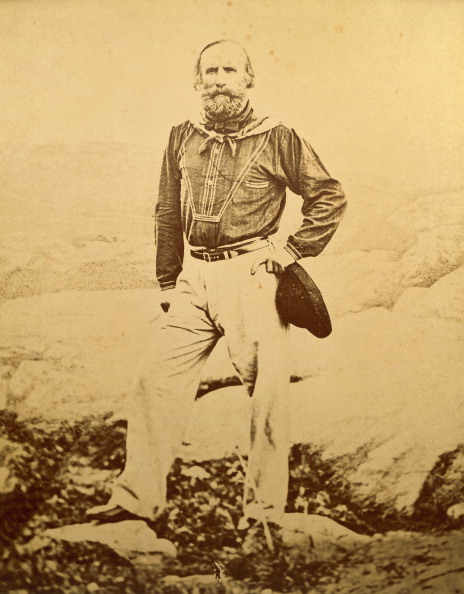

Giuseppe Garibaldi is one of the most outlandish figures of 19th-century history. A passionate Italian nationalist, he was constantly at odds with the politicians who could make his dreams real. With style and daring, he led guerrilla fighters in campaigns which resulted in the unification of a nation; only for politicians to swoop in and compromise his dreams.

Italy in the 19th Century

When Garibaldi was born in 1807, Italy had not been united since the days of the Roman Empire. Long dominated by outside forces, it was a collection of fractured kingdoms and principalities, with some of its territory controlled by the Austrian Habsburg Empire.

The idea of an Italian nation was on the rise. Nationalism was becoming popular all over Europe, as people sought to overthrow ruling empires. Garibaldi’s contemporary Giuseppe Mazzini gave shape to the movement for a united Italy. However, none of the rulers wanted to give up their power easily.

A Man of Action

Garibaldi was drawn to those ideas, but it was outside Italy that he first earned fame. After spending ten years on merchant vessels in the Black Sea and Mediterranean, he was involved in a mutiny in Piedmont, one of the Italian states. Wanted for sedition, he fled eventually reaching Latin America.

There he fought in the wars of independence that shaped that continent. Physically commanding and skilled in guerrilla warfare, he became well known as a general. During fighting in Uruguay in the 1840s, he adopted red shirts as the uniform for his troops, chosen because they were cheaply and plentifully available.

Rome

By 1848, Garibaldi had become tired of corrupt American politics. As he was returning to his native Nice, revolts broke out across Europe. Seeing a chance for his dream of a united Italy, he raised troops and fought in the Alps, to little effect.

A revolt broke out in Rome, headed by Mazzini. Garibaldi brought his volunteers and helped to defeat Neapolitan forces which had gone to restore the old order. Then the French intervened, and through a combination of trickery and military strength, forced the rebels out of the city.

Garibaldi tried to keep his army together. Harassed by Austrians and with few places of safety, the army fell apart.

Having also lost his lover Anita on the march, Garibaldi retired and tried to become a farmer.

Return to Action

He returned to action in 1859, at the invitation of the Piedmontese Prime Minister Count Cavour.

Cavour wanted to drive the Austrians out of Italy. He saw Garibaldi’s charismatic leadership and popularity with the public as useful tools. After maneuvering Austria into starting a war, he brought Garibaldi in as a Piedmontese commander.

Garibaldi had several successes in the battle. Meanwhile, the armies of France and Piedmont fought the Austrians in bloody battles that led to a treaty. The Austrians abandoned Lombardy, but little more was achieved.

Then news leaked of Cavour’s deal with the French, ceding them the city of Nice in return for their support. Garibaldi, a native of Nice, was outraged.

Garibaldi and the Thousand

Garibaldi gathered a thousand volunteers and headed out on his most successful guerrilla campaign.

Sailing to Sicily, the Thousand fought fierce battles against Neapolitan troops holding the island. At the start of the campaign, 25,000 professional soldiers occupied Sicily for the Kingdom of Naples. Against the odds, Garibaldi and his patriots beat those forces one group at a time. As they did so, their ranks were swollen by Sicilians eager to join their side. Foreign volunteers rushed to their idealistic cause.

Along the way, Garibaldi witnessed the terrible brutality of the Neapolitans against Sicilian rebels and the equally brutal reprisals against Neapolitan troops.

Milazzo

The final action in Sicily came at the small port of Milazzo. There, Garibaldi advanced his army in three columns following a bombardment of the town. Leading from the front as he so often did, he risked his life and inspired his troops.

The fall of Milazzo struck fear into the Neapolitans. Despite having a much larger force at Messina, they sought a truce.

Meanwhile, Cavour was politicking behind the scenes. He wanted Piedmont to gain control of Naples but not as a gift from the republican Garibaldi. While King Victor Emmanuel of Piedmont wrote in friendly terms to Garibaldi, Cavour stirred concerns about him elsewhere.

March on Naples

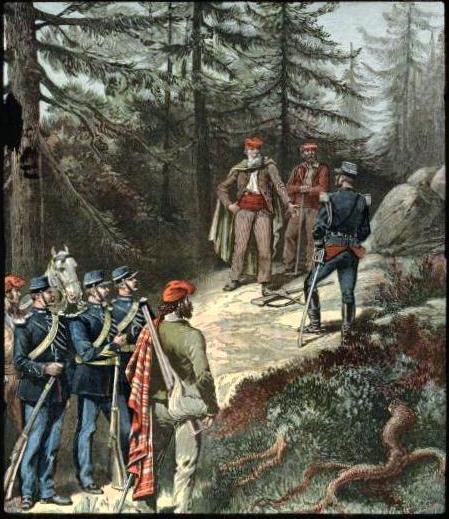

In August 1860, Garibaldi crossed to mainland Italy. His army of volunteers seized the town of Reggio and began a march through the Kingdom of Naples.

King Ferdinand of Naples was corrupt and unpopular with his people. Everywhere Garibaldi went he was welcomed as a savior. Locals provided him with information and the supplies he needed.

After Ferdinand had fled the city of Naples, his Prime Minister invited Garibaldi in. Traveling by train with a handful of men, Garibaldi arrived and was greeted by cheering crowds.

Volturno and the Vote

On October 1, Garibaldi fought the Neapolitans for the last time at the Battle of Volturno. It was a tough fight, Garibaldi having to take the defensive for once, but he won the day.

Cavour now took control of the situation. He announced a public vote, asking people if they wanted a united Italy under King Victor Emmanuel of Piedmont. The popularity of the nationalist cause allowed him to sever it from Mazzini and Garibaldi’s republicanism. Much of Italy was now united.

Last Gasps

Politically betrayed and in increasingly ill health, Garibaldi returned to farming. Over the next ten years, he came back for a series of ill-conceived attempts to seize Rome and Venetia. In the end, it was Prussia’s wars against Austria and France that enabled the Italians to take those regions.

In 1870, Garibaldi’s dream of a united Italy was complete. It would not have been possible without him, but the politicians had used him. Popular and famous around the world, he lived on in ill-health and obscurity until his death in 1882.

Source:

David Rooney (1999), Military Mavericks: Extraordinary Men of Battle.