Beginning in the later part of what historians know as the “Nordic Iron Age,” the pagan Danes built massive lines of fortifications along their border with what is now Germany. These are known as the “Dane-works” in English, the “Danewerke” in German, and the “Dannevirke” in Danish.

The purpose of these earthworks was to keep out invaders from the south, beginning with the Franks under Charlemagne, and later the assorted kingdoms and governments of the Germans. The last times the forts were used was in 1864, when the Danes and the Germans fought the Second War of Schleswig during the wars of German unification. Today, the remains of the fortress system are in Germany – that tells you who won in 1864.

There are a lot of myths and misinformation about Scandinavia during and immediately before the Viking Age (c. 790-1100). One of them is that the Northmen were isolated from the rest of Europe until they decided to burst out of their harbors to raid the rest of the Continent. Actually, the cultures of Scandinavia had pretty much always been in contact with the people to the south of them. They had traded, warred, inter-married, etc.

During the Roman Era, the tribes of the north, including the Germans and the Danes, had been in various kinds of contact with the Empire. When they were not killing each other, they were trading with one another. Goods from the areas of the Baltic States and modern Poland have been found in Rome.

However, during the last years of Rome and into the early Middle Ages, the lands of the former Roman Empire changed radically – they became Christian.

For a century or two before the Viking Age (c. 790-1100 AD) the super-power of Europe was the Carolingian Empire of Charlemagne (742-814). One of the emperor’s primary goals during his long reign was the spread of the Christian religion.

Charlemagne conquered the tribes of Germany, into Austria, and made vassals of the kingdoms on today’s eastern German border. In all of these wars, those tribes who were not Christian were given a choice: convert, or die. Historians estimate the death toll of the Saxon tribes in the tens of thousands or more.

The Danes were not Christian, and did not want to be. Their kings were also quite eager to hold onto their rich farm lands and strategic location between the North and Baltic Seas at the top of Europe.

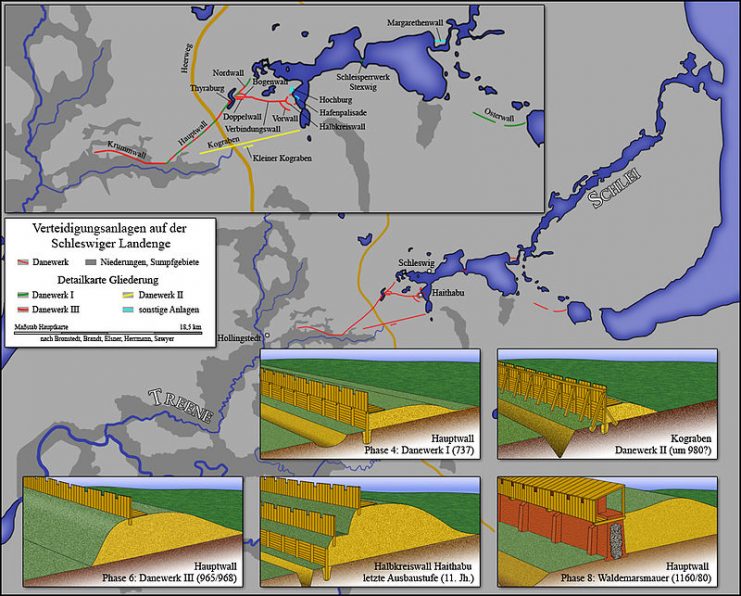

With the fall of the Roman Empire, and then in order to keep out the Franks under Charlemagne and his descendants, as well as the later German kings, the Danes began to build the Dannevirke in the years prior to 500 AD. The barriers were built in stages, with four main groups of fortresses built from the sixth century to the late 1100’s, by which time the Danes were Christian.

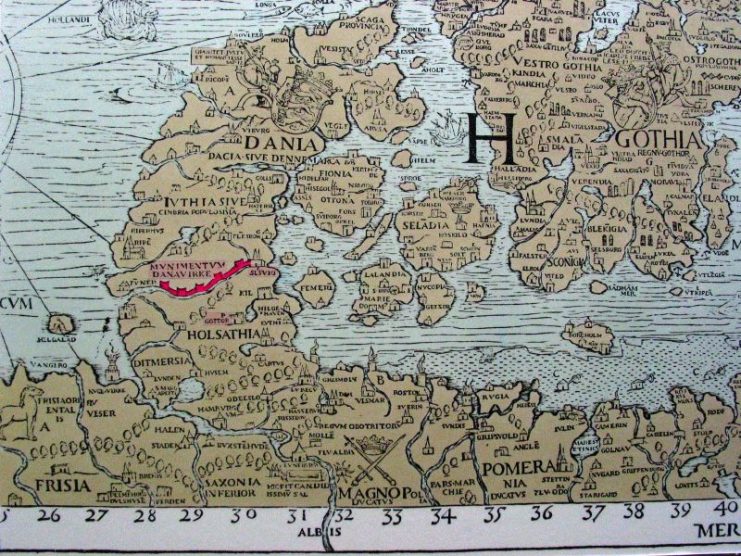

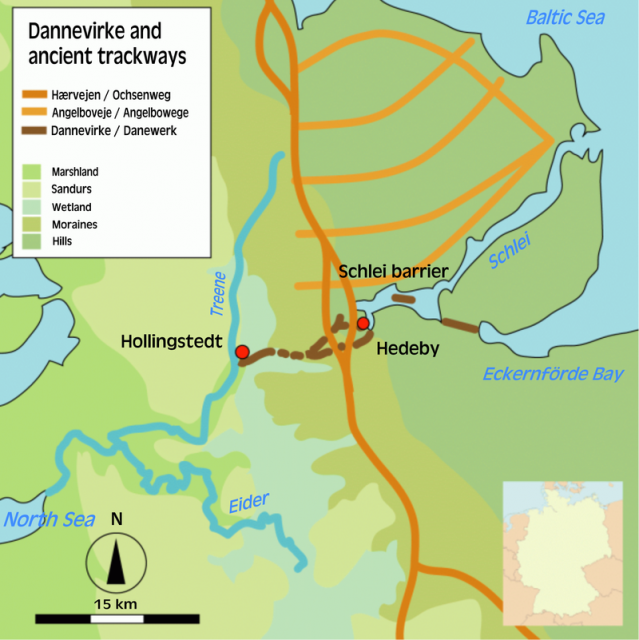

Located across the neck of Denmark, the Dannevirke are made up of several thick walls and trenches. Moving from west to east, the works end in the area of what is known as the “Schlei Barrier,” a long bay which an army can only cross by boat.

The western anchor of the works are the Eider and Treene Rivers, which formed a formidable natural barrier in the Middle Ages. The works were designed to defend an area of southeastern Denmark that is relatively open and easily traveled.

The barriers are about nineteen miles long, and the walls range in height from twelve to twenty feet. In recent years, archaeologists have determined that forward of the main walls were two other parallel sets of embankments.

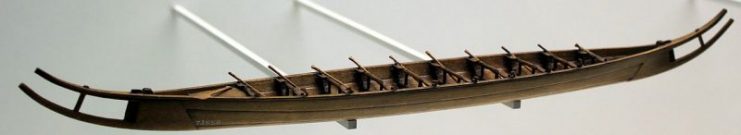

Between these two embankments was a canal, which allowed craft from the west to travel to the Baltic. Previously, historians believed that any shipping not going by sea around the Danish peninsula, which was not always possible, was dragged across the land on rollers.

Initially, the Dannevirke were only high earth-works, but by the mid-700’s the walls had been reinforced by massive wooden fronts, along with towers and, in some places, a stone wall. At times during the Middle Ages, places along the works were topped by palisades and finely worked masonry.

The naval forces of the Danes and the strength of the Dannevirke were effective in keeping out the Franks and other invaders from the south of Denmark for centuries. Though most people today believe that the height of Danish power was during the Viking Age, this is incorrect.

Between 1397-1814, the Danes either ruled or took part in two great empires – the Kalmar Union (1397-1523) of Denmark, Norway and Sweden, and the Danish dominated Kingdom of Denmark/Norway (1524-1814). During the latter part of great Danish power, and into the later 1800’s, the Dannevirke became a symbol of Danish strength and an object of national pride. The general public believed the works to be impenetrable, although in reality they were not. The Danish government encouraged this illusion to maintain a nationalistic spirit.

However, much like the French Maginot Line in 1940, the Dannevirke had become obsolete by the mid-1800’s. As tensions with Prussia, the most dominant German state and the impetus behind German unification, increased in the late 1850’s and early 1860’s, the Danes began to refortify part of the Dannevirke. Modern guns and barracks were placed along the length of the earthworks, and in some places the defenses were modernized.

However, when war broke out in 1864, the Prussian Army threatened to outflank the Dannevirke in the west, crossing the Eider and Treene Rivers rapidly to threaten the Danish rear and demonstrating how war had changed since the 1100’s.

Read more articles from us – 2000 Year Old “Barbarian” Battlefield in Denmark Yields New Evidence

Before the Germans could completely cut them off, the Danish forces manning the Dannevirke retreated northward to defend Copenhagen, the Danish capital. When the war ended, Denmark ceded a significant part of the southern portion of their country to Prussia/Germany, and today the Dannevirke lay completely within the German Republic.