The Haitian revolution is one of the most remarkable revolts in history. Unlike most revolutions, it was driven not by the middle classes but by oppressed slaves. It radically transformed the French colony of Saint-Domingue, turning it into the independent state of Haiti.

It was a radical moment; the only time slaves have freed themselves to take control of a country. With the resentment it unleashed, it became as cruel as it was inspiring.

Saint-Domingue in the 1780s

On the eve of the French Revolution, Saint-Domingue was the most profitable territory in the French Empire. Their Caribbean holding was filled with plantations. These produced mountains of sugar and coffee, luxury goods that sold for high prices in the growing European and American markets.

This achievement was built on huge inequality and oppression. Slaves lived lives of enforced labor and cruel treatment on the plantations. A legally enforced caste system gave whites massive privileges.

Most of the island’s people of color lived in chains; slaves outnumbering free people by ten to one.

Revolution in France

In 1789, revolution ripped through France. It was not a sudden, neat change from a monarchy to a republic. Many years of conflicting politics followed as ideas and factions vied for dominance.

The French Revolution was a middle-class affair. Men of growing wealth and education threw off the old ways to empower themselves. Few were dedicated to equality.

They adopted radical language which filtered through to Saint-Domingue, inspiring thoughts of freedom. It raised the question of whether slaves should be freed. Despite their ideals, many revolutionaries saw that it would undermine French economic power. They were loath to support such a change.

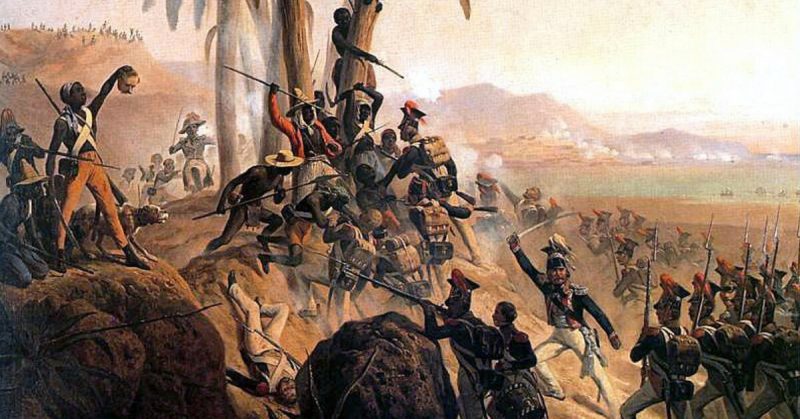

The Slave Revolt

In May 1791, the French government officially made people of color who were not slaves, Saint-Domingue citizens. This went against the existing caste laws. Whites on the island resisted. Fighting broke out between whites and the colored non-slave elite.

This turmoil inspired the slaves. On the night of August 21, 1791, a slave revolt broke out. Within weeks, they controlled the whole north of the island. 100,000 slaves rose in rebellion. 4,000 whites were murdered and their plantations burned down.

Foreign Intervention

Seeing an opportunity to take a French possession, both Britain and Spain got involved. They sent supplies to the rebels and military forces to the island. The British were mainly active at sea, the Spanish on land, although both used ships and soldiers.

France sent 6,000 troops, but nearly half of them succumbed to war and disease. Action was needed to prevent the island and its wealth falling to foreigners and royalists. Two French commissioners on the island declared all the slaves free, in the hope of winning colored support. This was backed up by the French government in February 1794.

Toussaint Louverture

By now, leaders had emerged among the slaves. Foremost was the smart, self-educated, and driven Toussaint Louverture. One of the slaves most successful military and political commanders, he initially sided with the Spanish. Having gained concessions from the French, he switched to their side and helped drive the English from the island.

Over the next few years, Louverture defeated internal rivals in a series of bitter conflicts. He occupied neighboring territory, freeing more slaves.

In 1801, Louverture declared an independent nation. In response, Napoleon sent a French army, supported by rivals of Louverture. In May 1802, he agreed to join his forces with the French Army in return for his freedom.

Despite promises, he was soon in a French jail, where he died.

Renewed Revolt

Even at the height of the uprising, there had not been true equality. Former slaves continued to toil on the plantations as cultivators, keeping Saint-Domingue’s economy running.

With the return of French power, it became clear that slavery was returning. Although he had risen to power on the back of radical change, Napoleon was willing to use whatever methods were needed to bring economic and military success.

In the summer of 1802, the cultivators rose in revolt.

Free at Last

The rebels had numbers and passion on their side, along with such capable commanders as Jean-Jacques Dessalines. The French had professional soldiers and the backing of a European state. What they lacked were enough troops and resources. Napoleon wanted to hold Saint-Domingue, but he was more interested in Europe. He would not spare soldiers from his wars there.

The British again intervened, blockading French ports on the island and giving their support to the rebels. For them, it was an extension of their war with France.

The last battle of the revolution was fought on November 18, 1803. It was a victory for Dessalines. The French expedition surrendered to the British rather than fall into the hands of vengeful ex-slaves.

On January 1, 1804, Dessalines declared Saint-Domingue to be independent, dropping its French name for an indigenous one; Haiti.

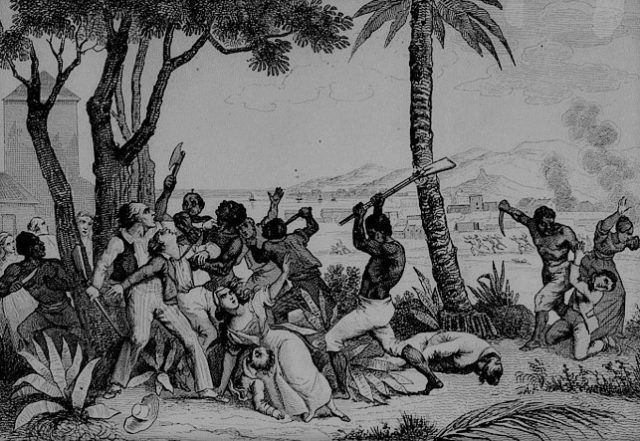

Reprisals

The war was over but the bloodshed was not. Led by Dessalines, the rebels inflicted brutal massacres on the whites. Dessalines justified this as vengeance for the atrocities committed by the white authorities. Those who died included many women and children. Polish soldiers who had defected from France, German colonists, and medical professionals were spared.

A True Revolution

Haiti was one of the few truly transformative revolutions. Most revolutions, from the English Civil War, through the American Revolution, to France’s long string of upheavals, have taken power from one group of wealthy men and handed it to another.

In Haiti, a slave class gained not just freedom but control of the government. A nation won its independence.

That freedom was gained through terrible struggle and cruelty. For the victors, 90% of the population who had lived in chains, it was worth the cost.