The city of Paris, in early October 1789, was a like a smoldering fire, just waiting for the gust of wind which would kindle it into a blaze. For over a thousand years, the reign of the French royal house of Bourbon had continued uninterrupted. For as long as anybody could remember, the power of the crown had been absolute.

The symbol of the power of the kings the great Royal Palace at Versailles, some fifteen miles from Paris.

The building had been begun by Louis IX, called the Sun King, and continued by his heirs and descendants. At first, it had been just a lavish hunting lodge, but over the decades of his long reign, and of those who came after him, it had grown into a megalithic complex of buildings. Barracks, residences, banqueting halls and offices, streets, courtyards and breathtaking gardens, and all designed with the most staggering opulence in mind.

But all was not well for the lords of the Ancient Regime.

In Paris in 1789, the mask was beginning to slip. It was an age of new ideas and new politics, and the population was becoming more politically aware, more active and more educated. Across the Atlantic, the newly formed United States of America had elected its first president, and was setting up its first young and hopeful democratic assembly.

Helped in no small part by the Kingdom of France, they had thrown off the yoke of British rule after a long and bloody armed struggle. Their struggle and their victory had proved that a people could govern themselves, without having always to submit to the dictatorship of a monarchy. After all, what was the rule of the monarchy but the rule of hoarded wealth, backed up by a complicit, sycophantic church and an ever-present threat of violence?

Things happened quickly that year, and politics was on everyone’s lips. In early summer, the National Assembly of the people was declared, its stated purpose to represent the interests of the common people instead of the wealthy clergy and nobility.

Elements of the military had rebelled, and a new revolutionary militia had been formed. In July, the Parisian fortress-prison of the Bastille was stormed and taken. In August, the National Assembly declared the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, and, also in August, the Assembly declared the abolition of Feudalism. In less than a year, the rule of the king had been seriously undermined.

In a market square in Paris, on the fifth of October, the women who spent their mornings buying and selling food and other wares were passionately discussing the political and economic situation in France. Taxes were high, bread was scarce, and the story of the banquet held last night at Versailles spread throughout the city.

It was said that the soldiers and officers there had, during an orgy of drunkenness and gluttony, trampled on and burned the tricolor flag of the new people’s Assembly. There were many market squares near to each other, and the rumor and buzz of anger leaped from stall to stall. An idea was formed. They would travel to Versailles, now, on foot, en masse, and take up their argument with the king himself.

A young woman, dressed in clean but ragged clothes, picked up a drum and began to beat a rousing tattoo. The sound caught at the hearts of all who heard it. A young man, Stanislas Maillard, who was popular and well known among the market women, began to shout; “à Versailles!” The cry was taken up throughout the streets, and the people poured forward to join the march.

It took around six hours to reach the palace. By this time, the crowd was many thousands strong, and though there were many men here too, the march was still very much dominated by the furious and hungry women of the market. By the time they reached the palace almost everyone present was armed. Exhausted, they made for the headquarters of the national assembly, which they occupied in force. As night began to fall the marchers had surrounded the palace.

The president of the National Assembly took a deputation of the market women to speak to the king. He, seeing the impossibility of his position, agreed without protest that food from the royal stores should be distributed immediately, and that further action should be taken in the coming days to counter the fear of famine in the city.

Meanwhile, two National Guard regiments which had been dispatched from Paris to control the crowd arrived, and their commander, Lafayette, left them to speak to the king. In his absence, they dispersed into the crowd, and in did not take long for them to realize which side they were on. Within hours, most of the soldiers had joined the cause of the market women.

It was about six in the morning when things began to get out of control. After the deputation to the king, some of the marchers felt their goals had been achieved, but the great majority remained unconvinced. They wanted to compel the king to return with them to Paris, and when they found an unguarded entrance to the palace they began to stream inside in greater and greater numbers. There were few guards in the palace, but one of them unwisely fired his musket into the crowd. What had up till now been a peaceful protest quickly boiled into violence. Guards who resisted the crowd were beaten and killed and several were beheaded. A great roar and cry filled the comfortable corridors if the palace as the furious people hunted for the bedchamber of the king and queen.

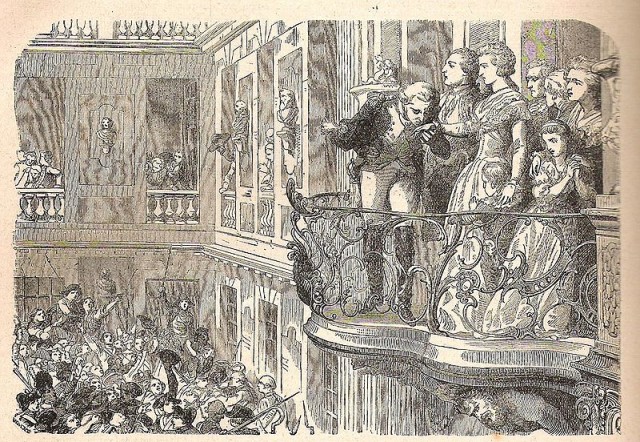

Most of the soldiers present were either already on the side of the revolution or were unwilling to fire on the people. It is very possible that the royal family would have died that night at the hands of the people if it had not been for the intervention of Lafayette’s National Guard. They were able to communicate with the Royal Guards in the palace and establish a swift truce. Lafayette himself came to the king and convinced him to speak to the people. The invading crowd, bloody and buoyed by victory in the palace, withdrew to the grounds and called for the king.

They were able to communicate with the Royal Guards in the palace and establish a swift truce. Lafayette himself came to the king and convinced him to speak to the people. The invading crowd, bloody and buoyed by victory in the palace, withdrew to the grounds and called for the king.

Louis XVI, appeared on the balcony, flanked first by Lafayette and then, in response to the demands of the crowd, by his deeply unpopular queen. Having no choice, he acquiesced to the crowd’s demand that he and his family should return with them to Paris. So it came that, three days after that first drumbeat in the Paris market, the women’s march escorted the Monarch, his queen, his family and most of his court, back to the city.

The march of the Market Women to Versailles was one of the most significant events at the beginning of the French Revolution. The power of the King was irreversibly curtailed, and he never again dwelt at Versailles. Some years later he attempted to flee Paris but was again dragged back by a crowd of citizens. He was guillotined three years later, marking the final end of the long unbroken rule of the kings of France.