Charles Edward Stuart landed on a tiny island off the north-west coast of Scotland with seven others in July of the year 1745. He was met by a small group from the Clan MacDonald and began to move south and east.

He rallied the clans to his banner as he traveled. By September, he had occupied Edinburgh and was preparing to march south at the head of an ever-growing army.

His grievance was an old one. It had been his father’s grievance, and his father’s before him. In Charles’ eyes, the crown of Scotland, England, and Ireland (as it was then) was his birthright, in a long line from father to son for hundreds of years. His father had fought to reclaim this crown, and so, when his time came, would he. He saw himself and his father as kings in exile. Religion and politics had been used to depose his grandfather, and he must have felt, as so many often do, that his cause – the Jacobite cause – was both Godly and just.

There was loyalty still in the Scottish Clans both to the ancient House of Stuart and to the religion of the old kings. Many Clansmen felt Charles’ grievance and willingly threw their weight behind him. By September of ’45 Charles was in command of an army at least two thousand strong, made up of men from seven different Highland clans.

They occupied Edinburgh on September 16th, after the man in charge of the Government forces, General Sir John Cope, had retreated with his disorganized and inexperienced troops. Sir John was in something of a tight spot, most of the Royal Army being in France at the time, and he was initially unwilling to face the Highlanders in battle. Sir John and Charles played cat and mouse for some days, until finally, they met at Prestonpans, west of Edinburgh and near the sea, on the 21st of September.

It was wholly dark. Below them, the Jacobites could see the fires burning along the front of General Cope’s army. Young Sir John was no fool. He feared a surprise attack in the night, so he had set fires and placed many men out in front of his army to warn of any advance from the Jacobite side. He had added to his army, and his force now outnumbered Charles’ by some few hundred men. There were carbine-armed dragoons on his left and right flanks. His main line of battle was made up of four musket armed regiments of foot, with the few poorly-manned artillery pieces he had been able to gather reinforcing the center.

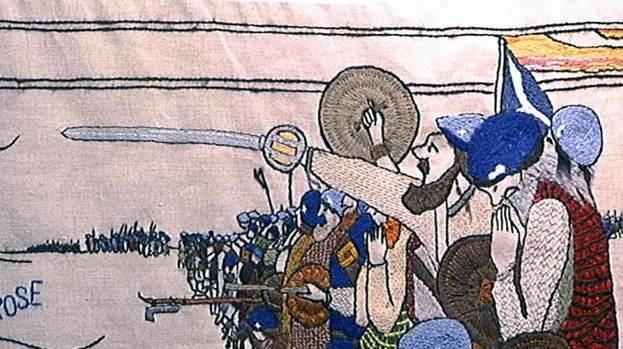

By this time in history, the cannon and the musket had long made their mark upon warfare. The power of artillery pieces and musket fire rendered the body armor of the old world almost useless, and in many cases, the bayonet had replaced the sword as the principal weapon for infantry. This was certainly the case for the government troops in 1745, but the Jacobites were still armed in an older style.

They had muskets and pistols aplenty, of course, but the signature weapon of the Highlander was still a fine, straight, one-handed sword with a basket hilt, accompanied by a round, studded light shield of wood and leather. They wore little armor, except perhaps some leather on the torso, and they went to battle bare-legged, with heavy woolen kilts around their hips. They were quiet and fast moving, hardy, fierce and proud.

Charles had arrayed them in two lines. He held the high ground, but his officers offered him little hope if he chose to send his sword armed troops in a frontal charge against Cope’s line. There was a wide ditch to cross, and marshland wet, deep and cold. Losses would be heavy. On the other hand, Charles was loath to allow the possibility of Cope’s forces giving him the slip in the night and was determined to give battle before that could happen.

There was a young fellow among his officers, a local man, the son of a farmer. He knew the area well and spoke convincingly of a pass through the marsh that could be used to bring Charles’ army round close to Cope’s right flank. Scouts were sent to investigate, and soon returned bearing the news that the path was unguarded.

Without delay, 500 men were dispatched to guard Cope’s only line of escape, the deserted high road west of the battlefield. Then the army began to move. A damp sea mist had started to creep across the low ground, and it was very cold. The Jacobite army positioned itself on the right flank of the Government troops, who, thinking they were to be attacked directly, managed a half wheel toward their enemy. But Charles did not give the order to attack.

His Clansmen were in high spirits, and keen to engage, but he was wary of the dark. The Highlanders might rout their enemies with a ferocious charge, but could he rely on them to maintain order after the engagement? He thought not, and if, in the darkness and confusion, Sir John Cope rallied his troops and attacked, in turn, the results for Charles could be disastrous.

A messenger arrived. It seemed that the group that had been sent to guard Sir John’s escape route had rejoined the main force, leaving the high road unguarded. Charles was chagrined at this and feared his enemy’s escape back to Edinburgh, but he gave the order to lie quiet and wait.

He remained in high spirits, lying quietly on the sodden ground with his officers, around half a kilometer from the government troops. The two armies waited.

In the dark hour before dawn, Charles began his secret advance. Under the cover of darkness, silence and the gathering early fog, the Jacobite army moved forward in three columns along the path that the young local officer had drawn to their attention. They passed the deep marshland without incident, and the first two columns found themselves lying hidden, not fifty yards from the enemy. Dawn began to break in the clear sky, and they immediately began to move.

The left and right columns of the Highlanders marched forward quickly. The center hurried up behind. The government troops attempted a turn. The right-hand column charged with a roar toward the artillery, whose crews fled in terror at the sight of them. The officers in charge of the cannon pieces held their ground and let off a deafening salvo. The stink of powder filled the early morning air as the dragoons and line infantry on the right fired through the mist into the terrifying charge.

The Highland onslaught slowed long enough to return fire to the Dragoons, and then they threw away their muskets as they gathered speed. There was a ring and clatter, and the steel of their swords flashed through the haze of mist and smoke. Sir John Cope’s right flank began to collapse. The Dragoons turned and fled. The Highlanders let out a great cry, and the government infantry swayed with the impact of the charge, wavered, then broke.

The line crumpled. The Dragoons and infantry on Sir John’s left flank fired prematurely, then turned and fled before Charles’ second column could reach them. The rout became total, and Sir John watched in horror as the Highlanders mopped up the remainder of his troops in the gathering morning light. General Cope himself stood firm with a small number of his Officers around him.

By this time, all order had collapsed in the Jacobite ranks, and the Highlanders ran hither and thither, slaying at will. They made a short stand by a thorn tree within view of the road but gave it up after losing two of their small group to a volley of pistol shots from a knot of the enemy. Back on the road, Cope rallied some 200 of his routed men around him and would have turned and fought to the last, but the remnant of his shattered force refused point blank to fight. Sir John Cope turned his few remaining men and made swiftly away.

Of more than 2300 men deployed on the Government side, only 170 survived the fury of the Highlanders. The Jacobites reported less than 200 casualties. It is a testament to their ferocity, and to the tactical ability of Charles’ officers, that the actual engagement was over in less than a quarter of an hour. The victory was so complete that when the Jacobites came upon the Government army’s baggage camp, its guards surrendered immediately, and Charles took a valuable prize of weapons, ammunition, food and sundries, and £5000 in gold.

The battle was a great boost to the Jacobite cause, and Charles’ army continued to grow and advance for some months until the disastrous engagement at Culloden in April the next year. At Culloden, as is well known, Charles Edward Stuart’s army was utterly defeated, and the rebellion was over. He went on to live a colorful life in exile in France, and then in Rome, where he died in 1788.

His remains are today interred in the Crypt of St. Peter’s Basilica in the Vatican.