Over one hundred people were crammed inside the small space inside a train carriage that would be better suited for transporting livestock. There was no water and food – there was hardly even enough air for the people to breathe in such a confined space. In the corner was a bucket with some stained sheets nearby – it was the single makeshift commode.

Thousands upon thousands of these trains crisscrossed the Third Reich from 1940 to the end of the Second World War, transporting so-called undesirables to concentration camps, of which there were many, as a part of the “Final Solution to the Jewish Question.” However, one such place is etched into our hearts and minds like the tattoos its residents received.

Many of the occupants inside the train wagon would never see the distinctive entrance consisting of a single square-shaped tower depicting the slogan “Arbeit macht frei,” or “Work sets you free.” For the rest, stone walls, barbed wire, and watchtowers surrounded the encampment.

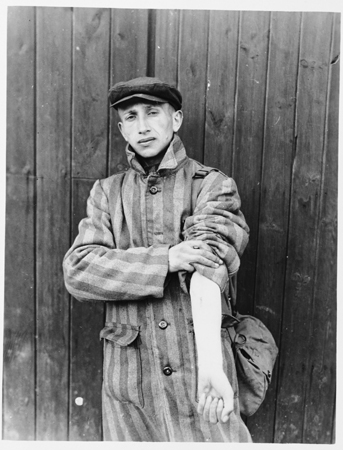

The train had reached its final destination. The often-shivering people inside had arrived at Auschwitz-Birkenau, the most infamous of Nazi extermination camps. It was the only place where the Jews would receive branding on their skin so that their Nazi jailors could better identify the corpses.

Upon disembarkation from the train, the occupants were herded together and examined by Nazi doctors to determine whether they were fit to work.

In some cases, twins or strong men were led away by the guards to be taken to the “Angel of Death,” Dr. Joseph Mengele. He was responsible for the deaths of hundreds of people as a result of his cruel experiments.

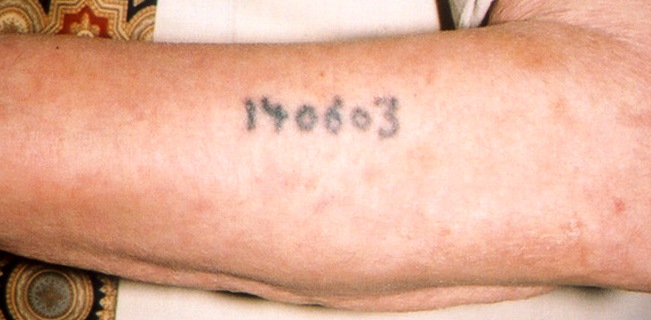

Those people who were too weak to work, children, the elderly, and pregnant women were led away to the showers where they would be killed by gassing. The remainder would receive a tattoo via a single-needle device, which pierced the outlines of a serial number into their skin.

It was a practice reminiscent of ancient Rome, when runaway slaves had the letters FGV for “fugitivus” burned onto their skin.

The system of tattooing was introduced at Auschwitz in the fall of 1941 and in neighboring Birkenau the following March, according to the encyclopedia of the American Holocaust Memorial Museum. Those were the only camps that used them.

How many millions of people were marked, either on the chest or the left forearm, remains unknown. Only those deemed fit to work were given a tattoo, so in some cases the numbers, although degrading, were even worn with pride, especially by those people with lower numbers indicating that they had survived several brutal winters in the camp.

“Everyone would treat the numbers from 30,000 to 80,000 with respect,” wrote Primo Levi, an Italian Jewish chemist, writer, and Holocaust survivor, in his memoir If This Is a Man? In it, he describes tattooing as part of the “dehumanization” process.

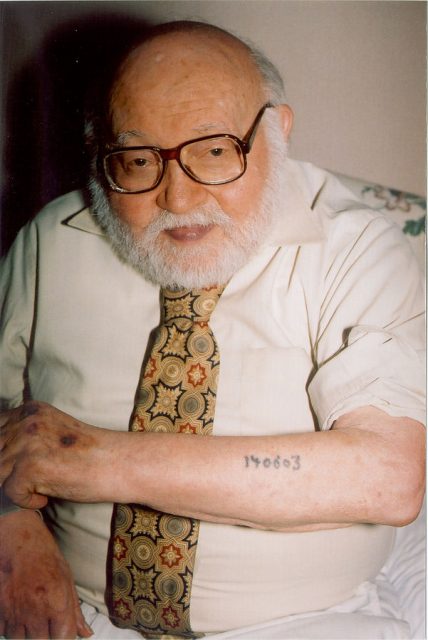

This pride and respect for the tattoo continued for many Holocaust survivors after the war. Eva Mozes Kor, a survivor who along with her twin sister was subjected to Dr. Josef Mengele’s experiments, said when asked about her tattoo that she would never remove it. She said that she was proud of her tattoo with the following words:

“By removing my tattoo, I would remove all the tragedy that happened to me? Unfortunately, the answer is no. So why should I submit myself to further pain so that I do not have to see that tattoo? It is kind of like my badge of courage. I actually like looking at it, even though it’s not very clear. That’s okay — I know why it’s not clear.”

Some people have even used their numbers in the lottery or as passwords.

However, on the other side of the coin, after the war many Auschwitz survivors quickly removed their tattoos or hid them under long-sleeved clothes.

For some people, the mere sight of that hateful ink on their skin was too much to bear, reminding them of the most degrading, fearful, and arduous period in their life. Other men and women removed the branding for religious reasons as the Torah forbids Jews from mutilating their body with ink.

Dana Doron, a 31-year-old doctor and daughter of a Holocaust survivor, interviewed about fifty tattooed former concentration camp inmates for the Israeli documentary Numbered, which she filmed with photojournalist Uriel Sinai.

When Doron asked the survivors whether lovers kissed the tattooed number like a sore spot, “some people looked at me with the question on their face ‘Are you crazy?’ and others said, ‘of course,’” she explained.

“For me, it’s a sore,” says Doron, who became interested in these numbers when she took blood from a tattooed arm during an emergency operation. “The fact that young people choose to be tattooed in this way is, in my view, a sign that we are still carrying around the wounds of the Holocaust.”

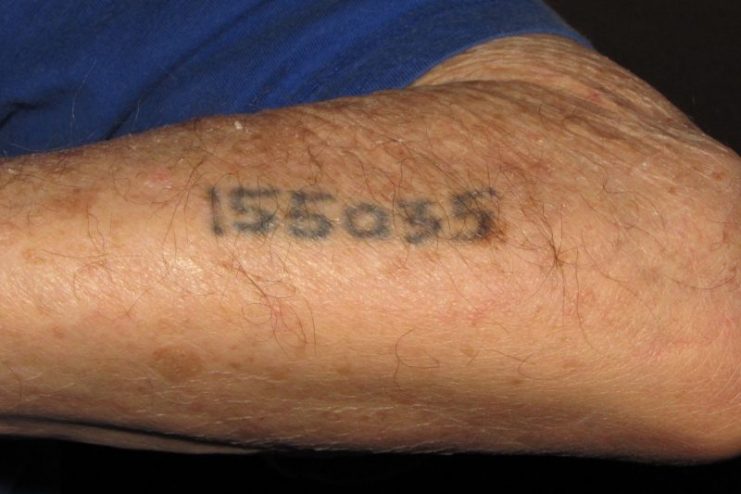

More and more, young Israelis are having their grandparents’ concentration camp numbers pierced onto their forearms. Not everyone can understand it. The reason is the desire of the younger generation to be forever connected with the Holocaust survivors.

Numbered also shows Hanna Rabinovitz, a middle-aged woman who had her father’s Auschwitz number tattooed onto her ankle after his death. The film also tells the story of Ayal Gelles, a 28-year-old programmer, and his grandfather Abraham Nachshon, 86, who both carry the same Nazi identification of A-15510 on their arms.

“This is something of an inheritance,” explained Gelles in the documentary. “In my view, it is provocative. Everyone is appalled, even shocked.” Gelles talks about a crucial experience in his own life: watching cattle being branded at a ranch in Argentina. That experience inspired him to get the tattoo and also become vegan. He did not tell his grandfather about his plans though.

“If I had known about it, I would have advised you not to do it,” said the grandfather to his grandson. Referring to his Holocaust experience, Nachshon added, “I dream about it every night.”

He spent several months in Birkenau, where his mother and sister died in the gas chambers. “Many times we ran away from the Germans. Sometimes I ran through the night. ‘Maybe they would not catch me this time’ was what I would think.”

“Every time I see the number, it reminds me to call him,” says Gelles. “I find it rather difficult to develop an understanding of people I do not know, places I have not been to, and of course the Holocaust. Now, I understand my grandfather better.”

It is the same for many other Holocaust survivors and their progeny. The main reason for keeping and getting the tattoo is that they want to be close and forever connected with their relatives who survived such a trying and gruesome time.

Also, they wish to follow the mantra of “never forgetting” in a form that continually provokes questions and discussions. Eli Sagir, who worked as a cashier in a small supermarket in Jerusalem, says people asked about the number at least ten times a day.

A policewoman once said to her, “God created forgetting so that we can forget,” recalls Sagir. “I responded by saying, ‘Because people like you want to forget that, we’ll have to relive it all over again.’”

When Eli Sagir showed her grandfather, Yosef Diamant, the new tattoo on her left forearm, he kissed her.

Sagir sported the very same number, 157622, that the Nazis gave Diamant at Auschwitz. Almost seventy years later, Eli Sagir went to a trendy tattoo shop after a trip to Poland with her school class. A week later, her mother and brother also had the six digits pierced onto their forearms.

“My entire generation knows nothing about the Holocaust,” explains Sagir, 27, who has had her tattoo for ten years now. “When you talk to people about it, they think that it’s like the Exodus from Egypt – from the Second Book of the Torah. That’s why I decided to remind my generation – I wanted to tell them the story of my grandfather and the history of the Holocaust.”

Diamant’s descendants belong to a small group of children and grandchildren of Auschwitz survivors who want to remember the blackest years of history with their own body. Since the number of survivors has dropped over time from 400,000 to 200,000, many individuals ask themselves how to keep the memory of the Holocaust alive.

The tattoo discussion ignites the question of whether this approach trivializes the symbols that have long been sacred. Regardless of the answer, the tattoo born in one of the most nightmarish places in human history has many an emotional and traumatic impact on the survivors and their offspring.

Some survivors want nothing more than to erase the memory forever, while others wear the symbol of subjugation and death with pride.

Ultimately, it’s personal. And Primo Levi is not the only one when he said: “My number is 174517; we have been baptized, we will carry the tattoo on our left arm until we die.”