Warriors need a reason to fight. Sometimes self-interest is enough, men and women fighting for pay or self-defence. But more often than not, ideology plays a part. Certain ideologies have proved particularly important in the history of war.

Religion

Whatever your beliefs, there is no denying that religion is a powerful motivator. The certainty of being right, combined with the promise of eternal reward, drives men to great and terrible things.

The cult of Mars, god of war, was important in the Roman army, where “Mars Triumphant” was among the battle cries. As Rome moved away from its old gods, the army stayed wedded to religion. The Emperor Constantine’s conversion to Christianity came on the eve of the Battle of the Milvian Bridge (312), where his troops carried Christian symbols into battle.

The most famous example of Christian religious war is the crusades. Initially launched against Muslims in the Holy Land, but also taking place in Spain and Eastern Europe, men travelled from all over Europe to save their souls by fighting in these wars. Their religious fervour and battle lust led to combinations of victory and atrocity such as the fall of Jerusalem.

Chaplains still feature in most armies, and while the Islam of Daesh/ISIS may not be that of most Muslims, religion is important in motivating their fighters.

Chivalry

Christianity gave the knights of medieval Europe little guidance on how to behave once they were caught up in a war – or at least little guidance that they liked. So a new ideology was born, combining aristocratic status, religious dedication and martial prowess.

Chivalry encouraged both courage and clemency. Rules limited who could be harmed, and how. Though it took some measures to protect civilians, its main purpose was to protect the aristocratic knights, so that they could live to fight another day. Men were to face each other honourably in battle, accept surrenders, and take part in formalised combats where everyone knew the stakes.

The glamour of the ideal warrior played a large part in defining chivalry. He should be pious, cultured and well presented, as well as a great warrior. Knights such as Geoffroi de Charny dedicated entire books to the rules of chivalry, even though they were loosely defined and much debated.

One thing remained a constant for chivalry – it was an ideology for the elite, unlike the mass appeal of religion.

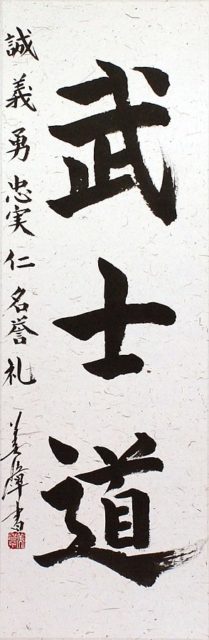

Bushido

The ideologies of chivalry and bushido are a classic example of the parallel evolution of ideas. On opposite sides of the globe, European knights and Japanese samurai were developing similar sets of military moral values. Societies with warrior elites, common throughout history, felt a need for rules to restrain them.

Though Japanese ideals of how a warrior should behave existed from at least the 11th century, it was not until the 17th century that the term bushido emerged and a specific ideology formed around it. Refined over the centuries, it gained its most widely recognised form in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with a growing emphasis on loyalty and self-sacrifice. Useful to Japan’s rulers, this form of bushido was influenced by Japan’s encounters, both peaceful and violent, with the wider world.

Bushido placed more emphasis on respect and self-restraint than chivalry. It also focused more intensely on honour – a sense of worthiness both internally and in reputation. Samurai who failed to live up to the high standards of bushido, for example through an embarrassing failure in war, would sometimes commit seppuku. This suicide by disembowelling was seen as an honourable death, helping to redeem past failures.

For the samurai, far more than the knight, honour was critical.

Nationalism

We now take national identity as a given. Patriotism is a prime motivator of soldiers in many modern states. But it was not always this way.

A sense of loyalty to a local community has existed since the dawn of history, with ancient warriors such as the Spartans going to great lengths to protect their homes. But the word “patriot” did not appear in the English language until the 16th century, and it was only in the 19th century that nationalism came to the fore.

In the 18th century, greater integration and better communications started to create a shared sense of national community in countries such as England, with its long standing and well defined borders. France and America developed strong national spirit through fighting outsiders during their revolutionary wars. The fire of nationalism had been lit.

In the Victorian era, nationalists started to see cultural units as natural countries, whether or not they were politically united. This led to wars inspired by nationalism, such as the unification of Italy, led by Guiseppe Garibaldi and completed in 1871.

With borders stable and centralised states the norm, nationalism became the default ideology driving war in the 20th century, taken to its terrible extreme in Nazism.

Socialism

The other great ideology to emerge from the 19th century and shape the 20th was socialism. The Russian Revolution was driven by the ideals of socialist reform, in its extreme form as Marxism. Revolutionaries throughout the world, from Peru to Vietnam, have taken up its egalitarian ideals to drive warriors into battle.

The Spanish Civil war shows political motivation at its purest. Idealists travelled from all over the world to fight on both sides of the war. Most fought in the International Brigades of the Republican side, hoping to forge a country that lived up to socialist, democratic ideals.

The failure of Communism and fall of the Soviet Union took much of the sheen off socialism, and in particular its hard line, revolutionary and militarised form. For now at least, it is receding into the history of war, along with chivalry and bushido. But with religion still motivating men thousands of years on, who knows what ideals will hold sway in the future.