In 1988, a US warship shot down an Iranian commercial plane, killing all onboard. The American captain and his crew were hailed as heroes, Scotland suffered, Libyans were punished, and we are still living with the effects today.

It began when Iraq invaded Iran on September 22, 1980. America sided with Iraq, and by the time it ended on August 20, 1988, about a million people lay dead. What ended the war, however, was an event that took place in the Strait of Hormuz.

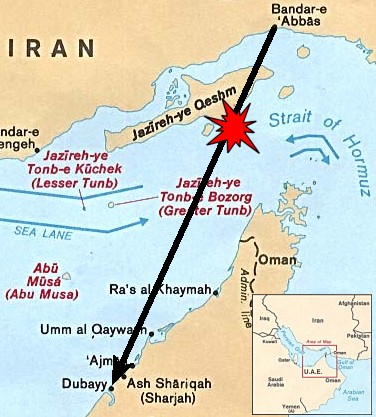

As the world gets 20% of its oil through this maritime route, the Iraq-Iran War extended to this vital Strait with disastrous consequences. On May 17, 1987, the USS Stark was hit by two Iraqi missiles – killing 37 US Navy men and wounding another 21. It was an accident, of course.

Despite this and other such incidents, commerce, fishing, and civilian transport continued using the Strait. To ensure they were able to, the US sent in its navy to protect them, as well as to enforce trade sanctions against Iran.

Iran responded by harassing ships – not just those from Iraq, but also those from neighboring countries. They also planted sea mines around their waters, one of which damaged the USS Samuel B. Roberts on April 14, 1988.

Four days later, the US retaliated with Operation Praying Mantis and attacked Iranian oil rigs in Iranian waters. The next day, they sank the Iranian frigate Sahand.

Non-Iranian merchant vessels and oil tankers paid the price. Many were harassed by Iranian Boghammar High-Speed Patrol Boats (HSPB), even in international waters.

On the evening of July 2, the Corona Maris merchant ship issued a distress call that began a tragic countdown. It was passing through the Strait when it was attacked by about 12 to 15 Boghammars. The USS Elmer Montgomery went to their rescue and escorted the ship out to the Arabian Sea.

The next morning, US Navy ships detected loud explosions. The USS Vincennes rushed to the Dhaulagiri, a German merchant ship, but they were not under attack.

It then went to help the Montgomery, and in doing so, crossed into Omani waters. That angered Oman, and the Vincennes was ordered to leave, so it did.

Captain Richard McKenna, Surface Warfare Commander in the Persian Gulf, was furious with Captain William C. Rogers III of the Vincennes. He was a hothead who had already stepped on many toes.

US military presence in the Persian Gulf was already a sensitive issue, and Rogers had no authorization to join the Montgomery which did not need any help. Hoping to de-escalate the situation, McKenna told Rogers to stay put and to send a chopper to investigate the explosions.

The helicopter pilot reported coming under fire by Iranian speedboats further north, so Rogers violated McKenna’s orders and entered Iranian waters.

Iran Air Flight 655 was an Airbus A300B2. On the morning of July 3, it was Captained by Mohsen Rezalan – a veteran pilot who was on his second leg of the day, and unhappy. He was 27 minutes late for his 28-minute flight from Teheran’s Bandar Abbas Airport to Dubai.

At 10:17 AM Iranian time (UTC +3:30), 655 finally took off and headed back the way it had come along commercial air corridor Amber 59 – a 20-mile wide lane which stretched directly over the Vincennes.

Down below, Rogers was having the time of his life blasting Boghammers when his men detected Flight 655. They contacted the plane but got no response. Switching to civilian channels, they ordered the “F-14” to change course.

If Rezalan received it, he ignored it. He was not the only commercial plane in the vicinity, nor was he flying an F-14 fighter jet.

Remembering the Stark and the Samuel B. Roberts while in the midst of a skirmish with Boghammars and other armed speed boats, Rogers gave the order to fire. There was a media crew onboard, that day, which recorded the jubilation on the bridge as they confirmed a direct hit on the plane.

Minutes later, the mood changed when they received radio broadcasts in both English and Farsi. The voices were desperate, pleading anyone in the vicinity to head for the crashed plane.

As they were already in Iranian waters, the Vincennes was the first to arrive. In the sea were 290 dead bodies – 66 of whom were children. There was no more cheering after that, not even from Rogers.

America denied having any ships in Iranian waters and blamed Iran for the incident. They also claimed that 655 was descending as if in attack mode.

They gave Rogers the Legion of Merit for his performance and the rest of the crew a hero’s welcome in San Diego. They would change their stories years later, but for others, it would be too late.

The day after the shooting, Iran’s Charge d’Affaires in Britain, Mohammad Basti, gave a press conference vowing revenge. He did not specify what Iran would do, only that it would be commensurate to the downing of Flight 655.

Iran was convinced the shooting was no accident – signaling America’s intent to enter the war. Exhausted, demoralized, and reeling from sanctions, they opened peace talks and formally ended the war in August.

Months later on December 21, Pan Am Flight 103 took off from London’s Heathrow Airport on the way to New York. Aboard were 243 passengers and 16 crew. As it flew over Scotland’s residential Lockerbie district, it blew up, killing everyone plus 11 on the ground.

Given Basti’s earlier threat, suspicion fell on Iran. The next day, a group calling itself the Guardians of the Islamic Revolution claimed responsibility – as did many others, including one calling itself the “Ulster Defence League.”

Blame eventually shifted to Libya. Buckling under the pressure, Muammar Gaddafi admitted responsibility for Pan Am 103, handed over the men allegedly responsible, and paid compensation to the victims’ families.

Despite many in the US Navy condemning Rogers, and revelations that initial reports about the incident were false, the US refused to apologize or admit legal liability for Flight 655. Although it did pay compensation to the victims’ families in 1996.

Iran has not forgotten, still convinced it was no accident. That is the mindset they take to the ongoing nuclear talks with America.