The First Sino-Japanese War was a culmination of Japan’s modernization. Having updated its military and industry, it faced cultural and political divisions that many in the modernizing country believed only war could solve.

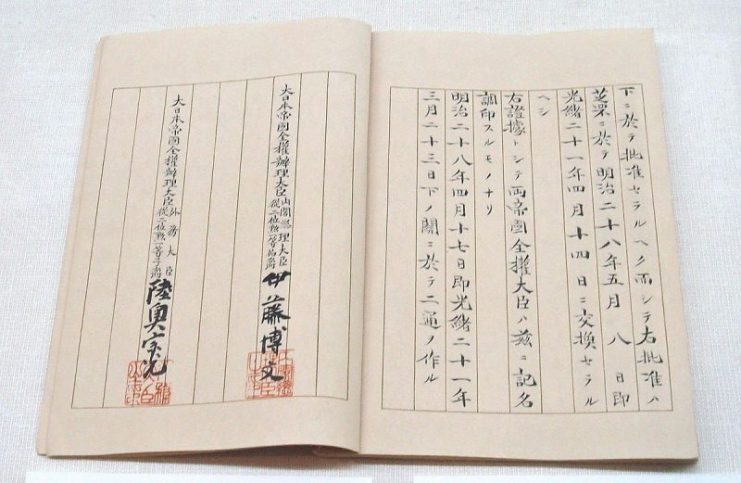

Eager to battle China over Korea, Japan took the first opportunity to do so, and, in 1894, Japan went to war against the floundering Qing Dynasty.

It did not take long for the war’s goals to shift. Nominally declared to secure Korean independence or at least Korean subservience to Japan over China, the war aims quickly escalated to include a strike into China’s heartland.

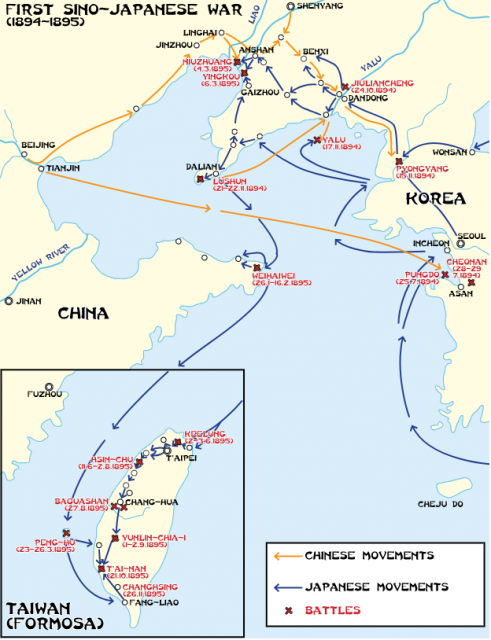

What the Japanese military planned was no more or less than the removal of China’s dominance in the region as the primary power, and Japan’s ascendance to that position. To do this, the military planned a joint naval-army strategy.

The Navy would secure the Yellow Sea and Gulf of Chihli, allowing Japanese troops and matériel to travel freely from Japan into Korea. The Army, meanwhile, would march through China until it capitulated. As a prelude to this, the land war would begin in Korea. It would not be the last time the peninsula nation found itself as a beachhead for other nations at war.

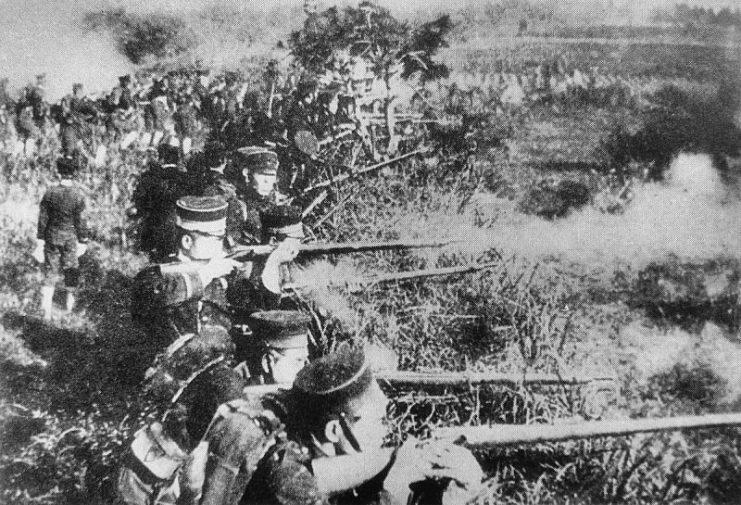

Despite the declaration of war not occurring until August 1st, the first battle of the war took place at Songhwan two days earlier. Forty thousand Japanese troops, having secured the Korean capital of Seoul, faced off against a similar number of Chinese soldiers.

The Chinese, entrenched to defend against the Japanese assault, faced a flanking maneuver from the Japanese and, after less than three hours of intense fighting, fled the battlefield, surrendering Seoul to Japan for the remainder of the war.

For the first three weeks of the war, Japanese troops slowly coalesced around Seoul. Poor roads and logistical support, combined with disease, took their toll on the Army, but the Chinese, demoralized from the loss at Songwhan and still recovering, failed to take advantage of the enemy’s thin lines and weakened state.

Once finally amassed, Japan’s Army prepared to strike at the next major Chinese base in the peninsula, Pyongyang. The hasty move northward was due both to the strategy of Japan for a rapid advance and also a need to strike before the Chinese forces properly organized their superior numbers.

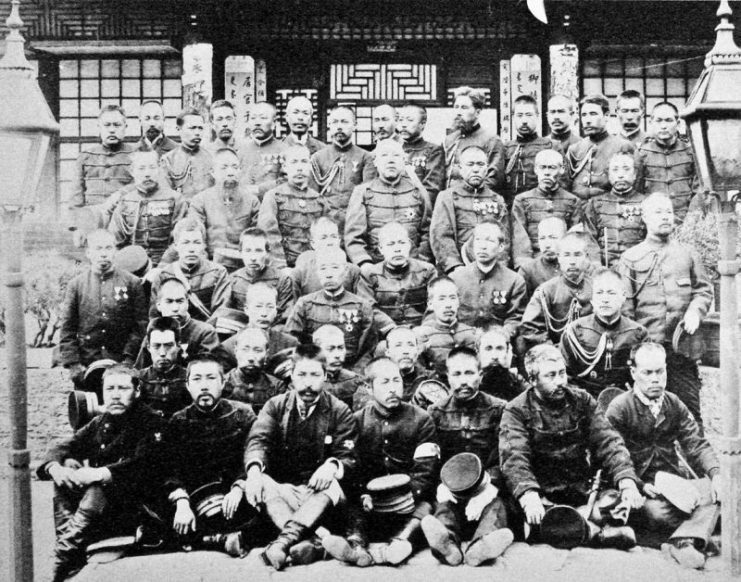

The Battle of Pyongyang, fought on September 15th, was a brief but harsh battle. Forts along the nearby Taedong River, as well as earthworks and hills, provided the town with ample protection. What’s more, the bulk of the Chinese Army in Korea was there, and the majority of them had received Western military training, and some even carried Western rifles.

The battle would be a true test of Chinese efforts at limited modernization versus Japan’s more ambitious efforts.

In their reports, the numerous war correspondents covering the war give a detailed account of the battle. “As I arrived,” one correspondent wrote, “our artillery had set up a gun emplacement about six or seven hundred yards to my rear and battle commenced between their guns and ours.”

While Japanese artillery flew “only ten yards above my head” Chinese return fire “passed no more than twenty to thirty yards above and occasionally landed around me.”

Ducking for cover in a Korean cemetery, the correspondent noted, “Whether they could see our artillerymen or not, the enemy turned all their guns on our emplacement, and the shells flew over like pouring rain….”

Eventually, thanks to the Wonsan detachment pushed to the right flank of the Sakunei detachment, “the Sakunei detachment finally seized the forward high ground and I used this as my opportunity to get away from the cemetery, going up to just behind the advance units.”

Elsewhere in the battle “the men under Colonel Sato had already turned on the enemy’s left wing fort, those under Major Yamaguchi the right wing fort. Our guns were placed as before and concentrated their fire on the central fortress.”

With the defending fortresses taken, Pyongyang, like Songwhan before, fell before the advancing Japanese. Despite China’s greater size, the two forces were relatively even; Japan amassed roughly around twelve thousand soldiers, while the Chinese had anywhere from fifteen to twenty thousand, depending on the source.

The Japanese out-gunned the Chinese with 44 guns to China’s 28, and the casualties reflect that; the Japanese officially suffered 108 dead, 506 wounded, twelve missing. It is thought the Chinese suffered over 2,000 dead and 600 captured.

The previous statistics hide the true difficulty the Japanese had; they were exhausted, underfed, dehydrated, and nearly out of ammo, and yet ordered to assault and force back their entrenched enemy.

Time and again the Chinese repulsed the Japanese advances, and it was only by flanking the Chinese rear that the Japanese Army prevailed. Despite these setbacks, Japan continued to advance through Korea, while the Chinese military withdrew to the Yalu River. At the border between Korea and China, the Chinese Army would make another stand against the upstart empire.