War is a lot of things. Heroic. Interesting. World-changing and life-altering. Many things move us, anger us, and frustrate us when we reflect on war.

However, most of all war is most often tragically sad. Lives are lost, many of them young ones that never really had a chance to live.

The men who fought WWI and the veterans who survived felt this tragedy keenly, particularly when they realized that millions of lives had essentially been lost for nothing. Because, despite that loss of life, nothing really changed.

Sure, borders did, but that just brought resentment for later wars. Economics got better for a time, but the seeds of the Great Depression were sown in WWI. Communism and its misery were also born out of WWI. The list goes on.

2018 marks the 100th anniversary of the Armistice that ended “The War to End All Wars.” In America, the event was folded into Veteran’s Day in 1954, but for most of Europe, November 11 marks the day when the First World War ended.

The United States came into the war late, with a determined President Woodrow Wilson attempting to keep the nation out of the conflict. Eventually, the Lusitania Incident and the Zimmermann Note pushed the USA to join the desperate Western Allies.

Almost overnight, millions of German immigrants, whether they were citizens or not, suddenly found their patriotism questioned. Rumors of German Fifth Columnists were rife, and even those of German descent whose families had been in the country for years or decades were suddenly looked at with suspicion.

The previously non-political frankfurter had its German name changed and became the “hot dog.” The hamburger became the very British “Salisbury Steak.” The popular German Shepherd suddenly became the “Alsatian” in honor of the Franco-German province that many in America wanted to see back in French hands.

In everyday life, places like Yorktown in New York and other enclaves of German immigrant families in cities around America became the subjects of police interest. Previously friendly neighbors became suddenly hostile.

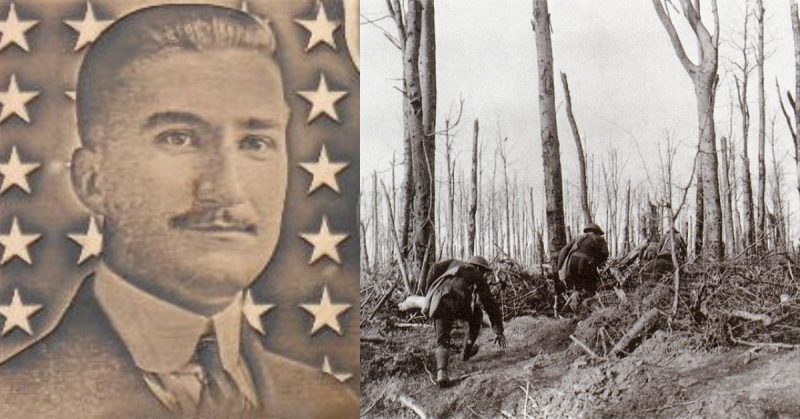

Henry Nicholas Gunther was descended from German grandparents who came to America in the 1800s. Both his father and mother were of German descent. All spoke perfect English. Henry’s given name was “Henry” not “Heinrich.” Still, Gunther was a German name, and it did attract some attention.

When war was declared, Gunther did not immediately enlist. He had doubts about fighting against his ancestral homeland but was eventually drafted in September 1917. He joined a local unit, the 313th Infantry Regiment “Baltimore’s Own,” part of the 157th Brigade of the 79th Infantry Division.

Because of his intelligence and experience as a bank officer, Gunther was swiftly promoted to supply sergeant, and was in that position when he arrived in France ten months after his enlistment.

While in France, he wrote a letter home which was intercepted by the censor. In it, he encouraged a friend back home to avoid the draft as much as he could – the conditions were miserable. This caused Gunther to be knocked down to private.

From September 12, 1918, to the very day the war ended, Gunther’s unit was involved in the fighting taking place in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, the first offensive with a sizable American presence.

Most of the American casualties of the war came during this operation. Like many of the British and Frenchmen who fought on either side of the American units, the Yanks soon learned that the war was not the walk-over they were told it would be.

Although the Germans gave ground and were on their last legs, they fought hard and were backed up by years of experience. Incessant shelling, gas, mud, and the beginnings of a flu epidemic that would take millions of lives worldwide filled the days and nights of the American “doughboys” with utter misery.

Most believe that Henry Gunther took the following action because he wanted to earn back the rank he had lost and its commensurate pay. But others believe that he also felt that some questioned his will to fight against his German “brethren” across no man’s land.

Whatever the case, on the morning of November 11, 1918, Gunther and the men around him knew the ceasefire was to begin at the 11th hour.

Though there are many reports of fighting raging on until the clock struck 11, in Gunther’s section of the line, all was quiet. He and his squad-mates were patrolling near the village of Chaumont-devant-Damvillers, close to the Meuse River.

They approached a German roadblock, manned by men who were ready, but quite clearly not eager, for a fight. Gunther and the rest of the squad took cover, to determine the intentions of the Germans.

Suddenly, Gunther stood up. His sergeant — and friend — Ernest Powell ordered him back down, but Gunther ignored the order. Instead, Gunther charged the German position with fixed bayonet and at full speed.

The Germans in the machine gun position tried to wave him off, knowing the war would be over in just hours, but Gunther kept coming, firing a shot or two at full gallop as he approached the German position.

The Germans had no choice, and they opened fire, killing Gunther instantly.

In the last “Order of the Day” issued by General Pershing written during wartime, Gunther is mentioned as the last American death of the war.

Gunther did get what he wanted – posthumously he was given sergeant’s rank, and his family got a pension. He was awarded the Divisional Citation for Gallantry and the Distinguished Service Cross.

No matter what conclusion we draw about Gunther’s actions – whether he was foolish, brave, or whatever – he lay down his life in the service of his country.

On November 11, 2010, the German Society of America laid a memorial plaque at his grave.