The Maori, originally Polynesians, who settled in New Zealand around the time between 11th and 13th century, are known for their distinctive warrior’s culture. Still existing today, the Maori people from the past were divided into fierce tribal groups, defined by their unique weaponry and fighting style. Throughout history, the Maori warfare tradition won them a reputation as some of the most dangerous warriors in the South Sea.

Mirror of the past – The Maori Warrior Traditions

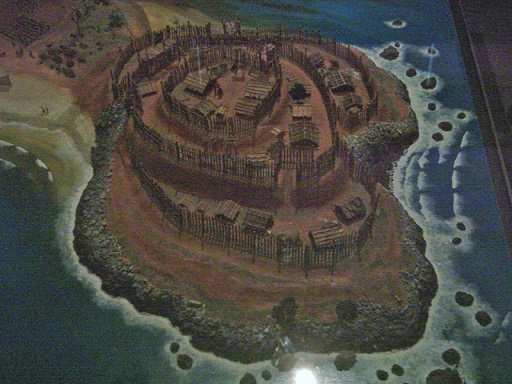

Among the deadliest warriors the British met during their expansions were the Maori. They had strict fighting code and lifelong tradition of war. Brave and fierce warriors, they were trained in the arts of war from an early age, in the usage of several unique weapons, fighting techniques and the now famous Haka dance. The Maori also built defensive fortifications (Pa) on strategic positions to defend their tribes.

The tribal wars of the Maori were always fought at the same time every year, following a strict code. The time between November and April was a time of war. During these months, the prime goal of every Maori warrior was to defeat the strongest enemy from the rival tribe in order to gain as much spiritual power called mana as possible.

The guerilla warfare of the Maori tribes was a tradition of dedication to the battle and something common for the New Zealand tribes. As the war season started, warriors were dispatched in units known as hapus. The number of warriors in a Hapu varied between 100 and 140. The war party of the Maori was not necessarily only from men since women were also trained in the arts of war. A Hapu was under the command of a war chief, who’s main priority was to motivate his men to fight. A Hapu’s war chief was expected to fight alongside the others and, if he died, the war party retreated.

I will kill you and I will eat you

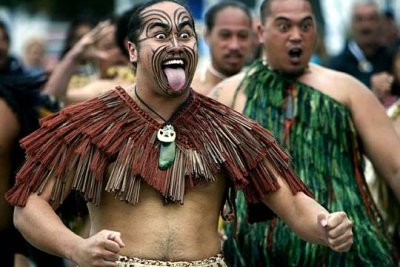

Before going to war all the warriors in the Hapu performed the Haka dance, during which they would wave their weapons, stick out their tongues, make frightening combat poses and noises bulging out their eyes. Combined with their unique tattoos the Haka dance was a warning to the enemy, which sends a clear message and inspired fear. The tradition of the Haka dance was important for the Maori, since if the performance was not perfect, the elders of the village thought of it as a bad omen for the upcoming war.

When dispatched, in order to get to the battlefield, which was traditionally at a certain place and hour, the Maori warriors went there either on foot or using canoes. The Maori canoes were one of the biggest of their time, measuring 70 feet and had the capacity to carry at least 70 men.

The main tactic of the Maori was the attack by ambush at dawn. They silently moved towards their enemies and when close enough would launch the attack catching the opponents off guard. Whoever survived the instant battle and was not from the winning side was killed, only those who managed to escape beforehand had any chance to live to fight another day and plot their revenge.

Those who were killed did not end up simply as a body on the ground. The protruded tongue of the Haka dance had a terrifying meaning – it warned an enemy warrior that he could turn into food for his opponent if he died. Maori ate those who they killed to consume their strength, using their bodily parts to craft weapons and tools. The Maori warriors were armed with spears and clubs of different sizes, deadly weapons made of wood, stone and bone.

Battle of Hingakaka

The largest battle ever fought in New Zealand was the Battle of Hingakaka in the late 18 century, between the two Maori armies of the southern alliance and those of the Tainui alliance. Up to 10,000 men under the leadership of chief Pikauterangi from Ngāti Toa fought to restore their honor near lake Ngarato.

Background

Three years earlier they were insulted over the fish harvest, which on their opinion was not distributed fairly among the districts. After they attacked the Ngato Apakura, who were the ones responsible for the fish feast, the latter were completely massacred for the insolence, and their bodies were cooked and eaten from the Ngāti Toa .

In the light of these events, Pikauterangi went on to gather the forces of the neighboring districts so he could initiate a war against the Tainui alliance.

Before the battle, the Tainui army realized they were vastly outnumbered. With a force smaller than 2,000 they stood no chance against the attackers. They couldn’t let the enemy find out their numbers were so small, and thus the allied forces decided to mislead them. Overnight they built several thousand more men – fake soldiers made of grass, wearing the traditional feathers on their heads. They were put in the back rows and even had assigned war chiefs. With the imaginary warriors on their side, the Tainui army appeared far more impressive.

The Battle

The leader of the Waikato tribe federation, part of the Tainui, Te Rauangaanga, prepared his men for the defense, placing them on the higher ground. He deployed them in three groups, waiting for the invaders to attack, and so they did. The Tainui enveloped them and broke their lines, creating a chaos in the midst of the invaders.

Pikauterangi’s army was confused and the defenders used this to their advantage attacking it from the flanks. At last, Pikauterangi was taken down and his men, following the long lasting tradition, tried to flee the battle, since their war chief had fallen. The Tanui’s other forces pushed the fleeing defenders into the marshlands next to the ridge where the battle was fought. Many of the warriors lost their lives to the marsh itself, and those who managed to cross it were welcomed by the rest of the Tanui alliance and killed on the other side.

The fight was far from over. Hingakaka was the cause of ever more bloodshed and tribal wars. Many more would die for revenge and honor.