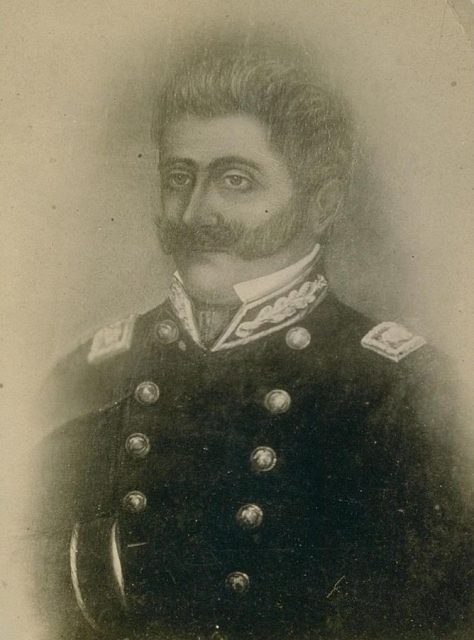

Far removed from Mexico City, the territory of California lived in near autonomy from its nominal government leadership, be that of the Governor of New Spain or the Mexican President. When the United States and Mexico went to war in 1846, obtaining California was a major goal for land-hungry US President James K. Polk.

American emigrants in the region harbored ideas of freedom. Some desired to join the Union. Others fielded greater ambitions of a free California Republic.

John C. Frémont, explorer and future politician, was partaking in a survey expedition of the future American west, known at the time as Mexico, when a runner with letters intercepted him en route. On May 8, 1846, Frémont, already in California, learned of the impending war and received permission to engage in “aggressive actions” against the Mexican locals.

Having already tried to rouse the locals of California into revolt against Mexico, Frémont received these orders and continued west. Having laid the groundwork through his previous efforts, Frémont and his group of less than a hundred men started gathering strength to take the Mexican military base of Sonoma.

Similar to what had happened in Texas, Americans started moving into Mexican California, ever in search of farmland. Many of these Americans settled around Sonoma, earning the ire of the local Mexican governor, Jose Castro. With tensions high on both sides, word reached the local Americans that Mexican General Mariano Vallejo was readying military support for the Governor to aid him against the American incursion and that a large amount of horses was being delivered to Vallejo to ride against the American settlers.

In response, the Americans, having organized in preparation of hostile Mexican or native assault, set out to intercept the horses. While all this was happening Frémont remained supportive but distant, lest he unduly involved the American government before it decided to involve itself.

Leading the raid against the Mexicans was Ezekiel “Stuttering Zeke” Merritt, who was said to be “a brawny, stern man of forty years age; he is hard-featured, has bloodshot eyes and a peculiar stuttering speech. His whole appearance and manner was that of a man moved by some revengeful intoxicating passion.”

Joined by William B. Ide and several others, on the morning of June 9, the party of roughly ten men set out to claim the herd of government horses for themselves.

Succeeding in their daring raid and taking the herd’s guard completely by surprise, the men brought the horses to Frémont’s camp. Horses secured, Merritt and Ide set about gathering recruits. By June 13, they had succeeded in swelling their ranks to over thirty armed insurgents intent on Californian independence.

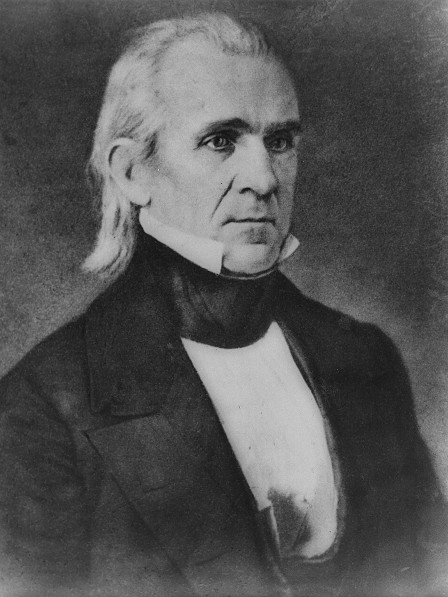

Upon starting a revolt, the insurgents now debated their next course of action. With the Bear Flag flying, many advocated immediate action against the Mexican government. Others, noting their limited numbers and lack of official US support, argued they should gather their forces and organize themselves into something besides a group of discontented emigrants.

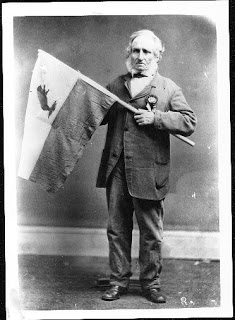

Ide took command of the operation, serving as a “Jackson-like” commander-in-chief to, in his words, “assume the responsibility” of leading the revolt. Thus declared, he issued a proclamation to the people of Sonoma, declaring the beginnings of a revolution. The Bear Flag Revolt had begun.

Ide then prepared a letter to Commodore Stockton, US Navy, whose arrival in San Francisco was expected to be merely a matter of time. In the letter, he wrote of a people forced to take up arms against oppression, hearkening to the Texas and American Revolutions in order to appeal to the American people and government.

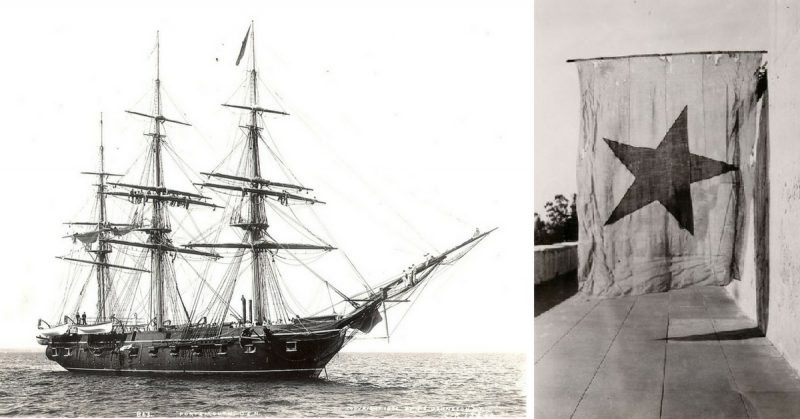

A man named William Todd, in addition to designing the Bear Flag, was appointed the new republic’s ambassador and tasked with delivering the letter to the Americans. John B. Montgomery, Captain of USS Portsmouth, the naval vessel en route to San Francisco, declared that while the United States would not directly support the independence movement, they would supply them with arms and ammunition should war between the US and Mexico break out.

With war clearly on the horizon, the heartened Bear Flag revolution spread its word of independence beyond Sonoma. Before long, the Sonoma rebels joined hands with the American emigrants residing north of San Francisco.

Few in number, and with Mexican forces thin on the ground, the revolutionaries main opponents were native Californians. Already used to a near autonomous way of life thanks to their remoteness from Mexico City, the locals loyally and ably defended their lands, both against the Bear Flaggers and the later American Army. As early as June 19, the two factions came to blows, when two Bear Flaggers running black powder were captured and brutally mutilated and killed by a Californian raiding party.

On June 23, Todd himself was captured by the locals, but a raiding party of revolutionaries succeeded in rescuing him. A man named William Ford led a party of nineteen men against nearly ninety Californians, in a daring raid made successful by Ford’s experience, aided by the element of surprise and a bit of luck.

The revolution was now completely out of Frémont’s hands and stood firm against the California guerrillas and limited Mexican forces. With the Mexicans on the move, Frémont, encouraged by confidential letters expressing little confidence in Ide’s leadership, gathered his following of seventy-odd mounted rifleman to join with the rebels at Sonoma before Governor Castro’s forces arrived. Departing on June 23, the intrepid surveyor arrived at Sonoma on June 25. After a turbulent meeting, the two men’s forces united to take the offensive.

While Governor Castro approached, the rebels decided to take the fight to California guerillas. Now numbering over two hundred armed rebels, Frémont led his men to observe the rebel force, under Ford, to assault the guerrillas. At roughly the same time, a Mexican captain named Joaquin de la Torre joined with the Californians to organize and move them to San Rafael. Ford’s forces followed them, engaging in skirmishes the entire way.

Castro, meanwhile, readied to move on Sonoma itself. Panicking at the revelation, Ide prepared his defenses as best he could, but fortunately Frémont, having circled back to join Ide, reached Sonoma before Castro’s assault. Castro and the Californians, however, outnumbered and outmaneuvered, decided against engaging the rebels, who, once they realized the enemy had withdrawn, returned to Sonoma as well.

On July 1, Ide advocated sending arms and men to San Francisco to arm Americans on the south side of the bay, spreading the Bear Flag Revolution across California. Frémont and others opposed the idea, and Ide, despite his insistence on being commander-in-chief, came to slowly realize he held no actual power over the revolution. Ide believed in an independent Bear Flag Republic. Unfortunately for him, Ide’s dream was his and his alone.

By that point, the United States Navy had arrived in California, and the Mexican-American War was entering the next phase of the campaign. Though local Californians would prove a formidable opponent, the region would eventually fall to the Stars and Stripes, ending Ide’s dream of a Bear Flag Republic and leading to America increasing in size and stretching from sea to shining sea.