The Crimean War holds a strange place in history. Remembered for a failed cavalry charge and a woman of mercy, the war paved the way for a united Italy, British Army reform, and military correspondence.

It was also a war witnessed by foreign observers, one of them a young American who would become infamous in the next war the United Stated found itself engaging.

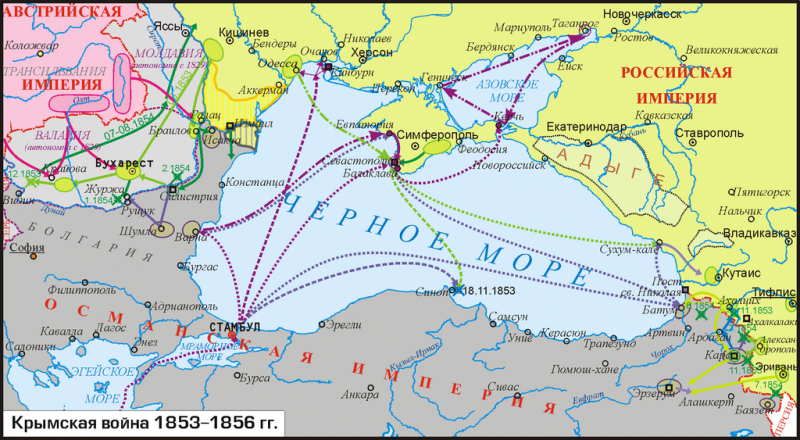

Fought from 1853-1856 between the Russian Empire and Ottoman Empire, over, as was so often the case, the Balkans, the matter of religious protection of the Ottoman’s Catholic population drew in France under Napoleon III, and the British followed suit following a threatening Russian naval action in the Mediterranean. Looking ahead to a united Italy, Sardinia threw their hat in with the British, French, and Ottoman’s against the Russian Bear.

As per the customs of the time, foreign officers observed the two sides wage their war, taking notes and reporting back to their homelands with observations and ideas about new tactics and the potential threat of the various participating factions.

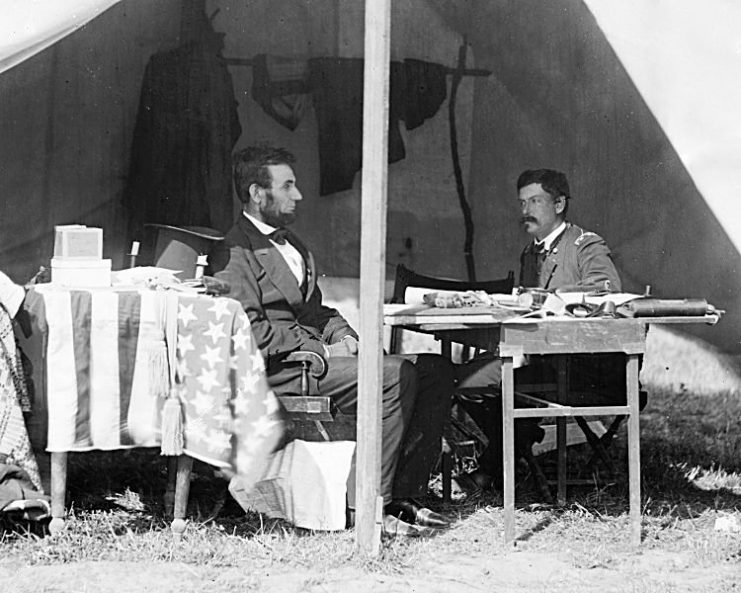

Among those military observers was a young American officer by the name of George B. McClellan. Before he gained his fame and infamy in the American Civil War, McClellan observed as the Old World once more went to war.

With the escalation of the war in 1855, United States Secretary of War Jefferson Davis, seeking to keep the United States military up to date, received Presidential approval to send a three-man team on a tour of Europe’s militaries and observe The Crimean War.

A young Captain not even thirty years old, McClellan joined the team along with two Majors; Richard Delafield and Alfred Mordecai. Though incredibly flattered by the choice that may well have made his future career, privately he complained of being sent to Europe with, as he put it, “those d–d old fogies!!”

The British quickly agreed to let the American observers witness their Army’s actions at the siege of Sevastopol, headquarters of the Russian Black Sea Fleet.

The French, however, balked, only agreeing to allow the Americans to observe the French forces if they agreed not to observe the enemy Russians as well. The French, for whatever reason, feared the Americans would reveal military secrets to the forces of the Czar. The three Americans refused and moved to petition the Russians.

Reaching St. Petersburg in mid-June, the three Americans quickly discovered their petition, easily granted by the Czar, lost within the primitive yet ponderously complex bureaucracy of the archaic autocracy. Not wanting to waste time, the American observers darted around northern Europe collecting material on Russian and Prussian military installations.

Russia finally responded to the three’s request in mid-August. Similar to the French, the Russians refused to let the Americans observe their forces if they intended to do the same with their enemies.

As by that time Sevastopol had already fallen, the three exasperated commissioners rejected the Russian conditions, accepted the French terms, and contented themselves that observing the abandoned Russian defensive works would have to be good enough for their reports.

On October 8, 1855, the three reached Balaclava, linking up with the British as they got to work once again. Though McClellan focused the bulk of his report on European militaries, he devoted the opening of his research on the war’s progress in Crimea.

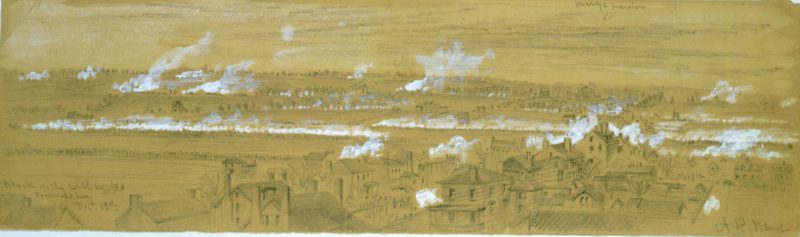

Though the city fell, the Russians still made their presence known, their artillery echoing in the distance. McClellan was grateful for the chance to be under fire, no matter how distant it might have been.

McClellan’s report included detailed postulations on the Battle of the Alma, an early step in the allied effort to reach Sevestopol. Of the Russian’s efforts at the battle, the young Captain wrote “Instead of offering battle at the Alma, two other plans were open for the consideration of the Russian.”

McClellan wrote that Russian strategy should have been to destroy the surrounding, smaller harbors to deny them to the enemy, leaving a defensive garrison in Sevastopol and using the rest of their forces “to operate on the left flank of the allies, in which case his superior knowledge of the ground ought to have enabled him at least to delay them many days in a precarious position.”

The Second potential plan, as McClellan saw it, was to “remain in the vicinity of the city, occupy the plateau to the south of it, and allow the allies to plunge as deeply as they chose into the cul de sac thus opened to them.” Both plans demonstrated a daring and tactical depth McClellan admitted partially born of hindsight.

Though Russian forces were forced to give up the harbor fort, the young Captain could not help but admire their stalwart defense, writing “They were attacked as field works never were before, and were defended as field works never had been defended.”

On the allies’ effort at the Alma, McClellan wrote that the combined forces should have “cut off the Russian army from Sebastopol, and following the battle by a rapid advance upon the city, to enter it, at all hazards, over the bodies of its weak garrison, effect (sic) their purposes, and either retire to the fleet or hold the town.”

The second thing they should have done, according to McClellan, was “cut off the Russian army of operations from all external succor on the part of troops coming from the direction of Simpheropol (sic), to drive them into the city, and enter at their heels.”

Черное Море = Black Sea, Российская Империя = Russian Empire (yellow), Австрийская Империя = Austrian Empire (pink), Османская Империя = Ottoman Empire (dark grey) I, Koryakov Yuri CC BY 2.5

Of the defensive works themselves, he observed “that the siege of Sebastopol proved the superiority of temporary (earthen) fortifications over those of a permanent nature. It is easy to show that it proved nothing of the kind, but that it only proved that temporary works in the hands of a brave and skilful garrison are susceptible of a longer defence (sic) than was generally supposed.”

Summarizing his section on Crimea, McClellan concluded that the United States should maintain its coastal defenses, improve the drilling and organization of its military, and maintain a small, disciplined defensive force. Looking to invasion rather than offense, McClellan noted the effect of artillery in support of defensive fortifications.

In McClellan’s reports we see the future battles of the American Civil War; the flanking efforts of Rebel generals making use of their knowledge of Southern terrain and the future earthworks of Vicksburg are echoed in the rapid movement of the allies and stalwart defense of Sevastopol by the Russians.

Further ahead, the use of artillery in support of defensive trench works foretells the bloody stalemate of the Western Front. Though McClellan did not lead Union forces long enough to see their full echoing in the actions in Crimea, the future of warfare is clear in his report, and, had he foreseen the lessons on which he wrote, his own campaigns in Virginia may have ended very differently.

Cited Sources:

McClellan, George B., Report of the Secretary of War: Communicating the Report of Captain George B. McClellan, (First Regiment United States Cavalry,) One of the Officers Sent to the Seat of War in Europe, in 1855 and 1856, AOP Nicholson, 1857.

Sears, Stephens W., George B. McClellan: The Young Napoleon, De Capo Press, 1999.