Seeing the success and growth of the communists, Chiang Kai-shek and his allies began an all-out war with them.

In England in 1215, King John was forced to sign the Magna Carta, which began the slow process of limiting the power of the English monarchy. In 1776, the delegates to the Continental Congress in America signed the Declaration of Independence.

In 1789, French crowds, tired of the oppression of the upper classes and the King of France, seized a symbol of that oppression, the Bastille, and the French Revolution began.

The People’s Republic of China has its “founding myth” as well, though, like the events mentioned above, the events in China in the 1930s really happened. In 1931, the communist Red Army began a 4,000-mile march for survival against its nationalist foes. Even committed enemies of the communist state are forced to admit that “The Long March” was one of the most amazing feats of modern military history.

The enmity between the Nationalist government of Chiang Kai-shek and regional warlords ostensibly under his control, and the Communists, went back a long time and was in many ways just another offshoot of the many uprisings and peasant wars that had been fought between the upper and lower classes in China.

In 1911, the Nationalists under Sun Yat-sen had overthrown the last imperial dynasty of China, the Qing, and established what Sun hoped to be a more fair and equitable form of government. Though some real changes did take place, most Chinese people – and the bulk of the population were peasants in the countryside – did not see any real improvement in their lives.

Their lives were brutally hard: subsistence farmers were subjected not only to great natural catastrophes, but also widespread abuse by the landlord class and the warlords which had divided China into their own private fiefdoms to be squeezed dry.

Enter the Communist Party, which had been formed in 1921, just a few years after the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia.

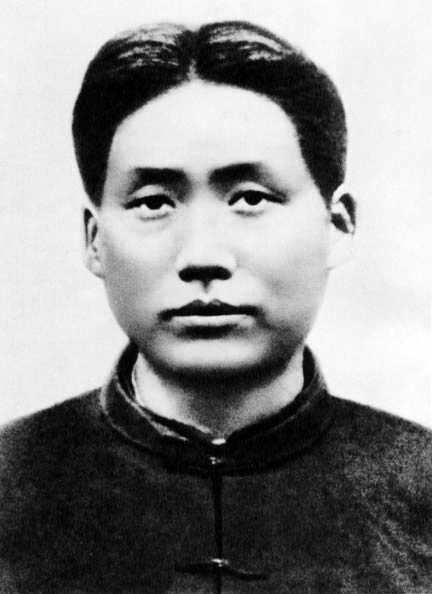

Though at the time, he was just a young revolutionary, one of the bright stars of the party was Mao Zedong, who had initially been a member of the Kuomintang, the Nationalists, but had become rapidly disillusioned with the slow pace of change in China and the corruption that seemed to be passed down from ruler to ruler from the mists of time.

https://youtu.be/k0l1RTiSnaU

Mao joined the Communist Party early – but he was not its founder. He did set up a branch in Hunan province, where he was from, and made a name for himself as the head of a revolutionary bookstore, which spread communist ideals and propaganda throughout the large region.

He was also one of the original delegates to the first National Congress of the Communist Party in 1921, and soon became party secretary for Hunan. Don’t let later events and terms fool you – “Party Secretary” back then meant not much more than a title.

Soon, people were flocking to the communist banner, because between the corruption of the Nationalists, the abuses of landlords and the local upper class, and the division of coastal China into “concessions” for foreign powers, many Chinese felt as if communism was the only way out of their nation’s many predicaments.

By 1927, the Communists had not only grown by leaps and bounds, but in the hinterland of the country, away from the slightly more modern and industrial eastern coast of China, they had begun to form an army, and establish revolutionary cells throughout the nation.

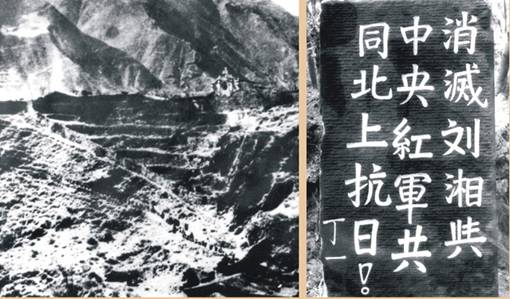

Seeing the success and growth of the communists, Chiang Kai-shek and his allies began an all-out war with them.

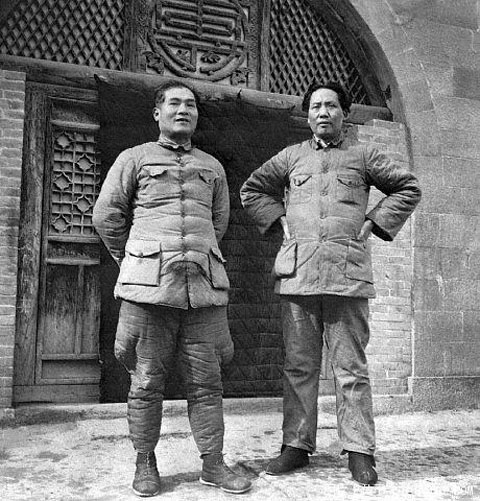

By this time, Mao had established his credentials as a revolutionary thinker and had some intriguing ideas on guerrilla warfare, which he was to build on throughout the war.

Also by this time, the Communists felt strong enough to declare their own republic in Jiangxi province, in the nations’ southeast. Mao was elected Chairman of the new republic, and while he had amassed quite a bit of power, still had to confer and sometimes defer to other committees and individuals.

Between 1930 and 1934, Mao and his generals developed successful guerrilla tactics and frustrated Chiang’s army at almost every turn. Still, they were essentially limited to Jiangxi, though the Communist Party did have cells and organizations throughout the country.

Coming close to catching and trapping the main Communist force many times, but never being quite able to do it, Chiang amassed 700,000 men at the borders of the province in 1934, with the idea of squeezing his enemy into a smaller and smaller space.

The first part of this siege was a disaster for the Communists in general and Mao in particular. Chinese peasants caught in the middle suffered most, as always – hundreds of thousands died of starvation and disease when Chiang cut off the province and many of its most productive areas. Mao was removed as chairman for not being able to develop a strategy to break Chiang’s siege.

The siege consisted of essentially “walling in” the communist forces by erecting fortifications and strong-points around their areas of control. Unable to destroy these fortifications, the communists faced not only defeat but annihilation.

Luckily for Mao, the men that replaced him in charge of the Revolutionary Army were not up to the job and replaced Mao’s guerrilla tactics with conventional ones.

While Chiang’s army was not the most motivated in the world, many of its officers and some of its noncoms had been trained by ex-German Army officers, who went to China to continue their military careers after defeat in WWI, and to collect handsome paychecks.

In conventional battles, the better equipped and trained Nationalists won almost every time, and the Red Army was decimated.

The Communists knew they would lose if they stayed in Jiangxi, so they elected to try to break out of the encirclement at its weakest points. In the evening of October 16th, 1934, they began to move.

Jiangxi is a large province with much rugged terrain, and at the time, few roads. It took several weeks for the Nationalists to realize that the bulk of the Communist forces had fled, due to rear-guards having kept up a steady volume of small-scale attacks.

The Red Army force was made up of about 86,000 troops, and 15,000 other personnel. Horse-drawn carts and the backs of the men made up its transport.

The line of marchers extended 50 miles. The legend of Communist Chinese troops being good night-fighters began during the Long March when most of their movements took place under cover of darkness.

One of the first memorable moments of the Long March was a disaster. The Nationalists had recovered and blocked the Communists’ route along the Hsiang River, erecting strong-points along the way. More than half of the Red Army was killed, wounded or captured in the battle crossing the Hsiang.

After this debacle, Mao slowly began to regain his position, pushing for more guerrilla tactics, which he felts suited an outnumbered army on the run.

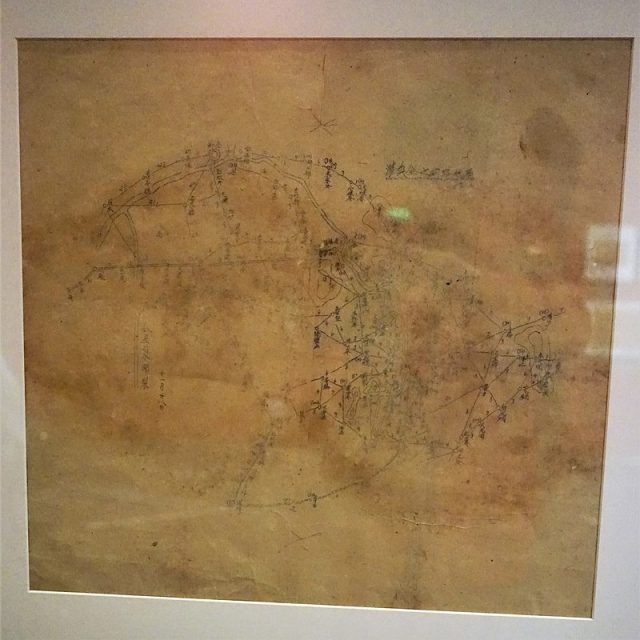

Taking a pause in the captured city of Tsuni, Mao re-established his power during a meeting of Party leaders. Instead of one long column engaging the enemy in conventional battles, the Communists would break up into smaller groups and take different routes to their new destination – Shaanxi Province in the far northwest of the country – a remote area that would perhaps allow the Communists to reform, reorganize, and rebuild in relative peace.

Over the course of the next months, the Communists would cover over 4,000 miles in an epic twisting, turning route, evading encirclement and defeat by the much larger Nationalist Army. They crossed 24 rivers, and 18 mountain ranges of varying size.

The number of troops making it to Shaanxi was only 4,000 – most of the rest had died along the way, but a core of an experienced and battle-hardened army was made.

Small Communist contingents from other parts of the country made it to Shaanxi as well, which the Communists did use as a base, fighting both the Nationalists and the Japanese and setting up a communist government with all of its trappings – both positive and negative.

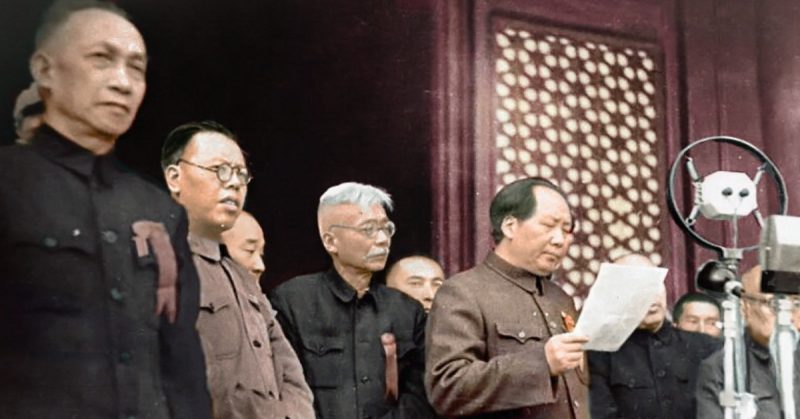

The Long March established Mao as the preeminent personality of the Chinese Communists, which he was to enjoy, except for one brief spell, until his death in 1976. Long March veterans were treated almost as gods within Communist China for years, many of them settling into positions of power and esteem.