The Duke of Marlborough is widely regarded as one of the greatest military commanders in British history. Though he is famed for his battlefield successes, one of his greatest achievements happened away from the roar of the guns, yet proved as decisive as any clash of arms. This was the march to the Danube.

The Man and the War

John Churchill, the first Duke of Marlborough, transformed the image of the British army. From 1702 to 1711 he led that army – which after 1707 included Scottish as well as English and Welsh troops – in a series of stunning victories in continental Europe.

For the first time since the Middle Ages, the British went from a middling force on the fringes of European warfare to the most highly respected army on the continent.

The importance of Marlborough himself is demonstrated by the swift decline of this reputation after he was replaced as commander in 1712.

The conflict in which Marlborough played such a decisive part was the War of the Spanish Succession. Raging from 1701 to 1714, it engulfed all the major European powers in a single armed dispute, in a way that would not be replicated until the Napoleonic Wars nearly a century later.

As with that later war, there was a huge amount at stake, with armies tens of thousands strong marching across the Low Countries and western Germany.

A Challenging March

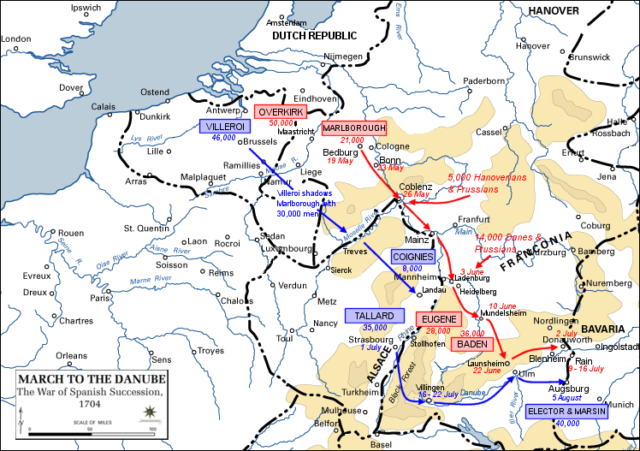

In the late spring of 1704, Britain and her allies were on the defensive. Their opponents, consisting of France, Bavaria and one faction among the divided Spanish, had gained the initiative. The Bavarians and French were marching on Vienna, threatening to knock out Austria, one of Britain’s allies.

To counter this, Marlborough decided to make a swift march into Germany to threaten the Bavarians. Starting on the 19th May, he marched his army from the Spanish Netherlands to the Danube, to meet up with Austrian forces.

Though the march would mostly be through friendly territory, it would face the constant threat of enemy action and the challenge of supplying thousands of men while maintaining a speedy march.

A Challenging Army

The material of which Marlborough’s army was made was challenging in itself. Neither England nor Scotland – the two countries were constitutionally separate until 1707 – had a standing professional army on anything like the scale required for this war.

As a result, the ranks were often filled with prisoners, from the most hardened felons to malnourished debtors, none of them particularly inclined to good military discipline.

The officer corps was little better. Commissions in the British armies were bought and sold rather than being awarded on the basis of merit. Though many officers were consummate professionals, just as many spent their time drinking, gambling, duelling and generally neglecting their duties.

This was the force that Marlborough whipped into shape and then marched across Europe.

Friendly Logistics

Marching through friendly territory had its advantages, but it also had a huge drawback, and that was the challenge of obtaining supplies.

Ever since the Middle Ages, British armies had an inglorious tradition when fighting in Europe of pillaging the lands they passed through, obtaining their supplies by stealing them off locals. This was fine when they were in enemy territory, or even disputed regions they wanted to bully into submission. But it could not be done in friendly areas.

Instead, Marlborough relied on winning cooperation from local people and using prearranged supply chains to buy and ship what he needed. Working from a base at Frankfurt, Solomon and Moses Medina combined local contractors and British gold to arrange for food and fodder to be ready, legally obtained and with transportation, ahead of the marching army.

To achieve this, supplies had to be ordered two weeks in advance, accepting prices that rose as food was eaten up and locals realised how urgently Marlborough needed their goods.

The Scarlet Caterpillar

The British army left Bedburg on 19 May and reached its Austrian allies at Launsheim on 22 June. 40,000 men, together with horses and support staff, marched east in their red coats, earning the column the nickname “the scarlet caterpillar”.

Every fourth or fifth day the troops stopped to rest and prepare for the next stage of the march. On those days, they set up their ovens and baked bread, as well as doing the repairs that would inevitably become necessary in an army on the move.

Not everything that made up the army travelled with the caterpillar. Spare leather goods in the forms of shoes and saddles lay ahead of them at Heidelberg. Much of the ammunition for the cannons travelled separately in guarded convoys.

As it advanced, the army forage across an area of 1,000 square miles, consuming 10% of all the local reserves of bread, meat, wine and beer.

It was a very hungry caterpillar.

Maintaining Order

Maintaining this march required rigorous organization and discipline. The army often set out at three in the morning, arriving at its next camping ground by nine.

Supplies were usually at the rest site in advance, so that all the soldiers had to do was pitch their tents, light their cooking fires and settle down to rest.

Leading an army in the age before general staff, Marlborough relied upon his personal staff and regimental officers to maintain order and communications. His ability to make good use of these men was one of the reasons he had such phenomenal success.

Marching to Victory

At the end of the march, Bavaria lay exposed before the British and Austrians. When the Bavarian leaders could not be convinced to abandon their French alliance, Marlborough and his allies forced them to battle. On the 13th of August, at the Battle of Blenheim, Marlborough achieved one of his most famous victories.

The Bavarian threat was neutralized, Vienna was saved, and the precarious Grand Alliance was preserved. He would go on to name his vast country house – the most spectacular non-royal residence in Britain – after the battle.

It was all possible thanks to the march on the Danube.