However hard they are trained, all armies face some problems with discipline. Anything from shirking tedious duties to running on a bloodthirsty rampage can undermine the good order on which successful armies are built. Modern armies mostly deal with this through the withdrawal of rank or privilege, and occasionally with imprisonment. Some armies went to more violent extremes.

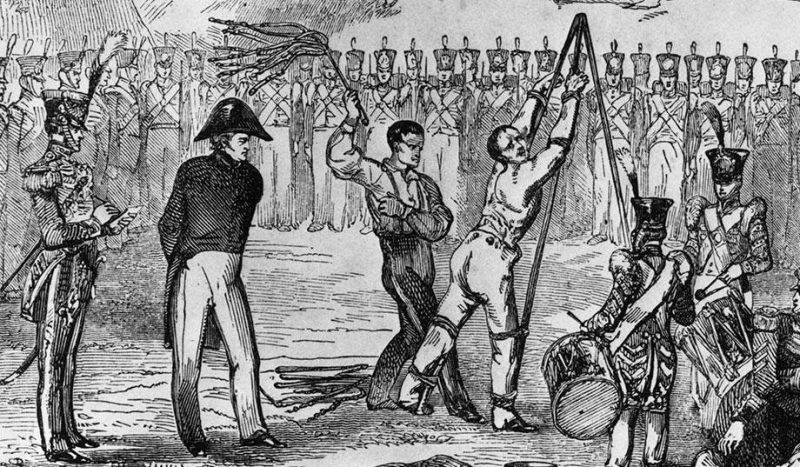

Beatings

Painful but non-lethal violence has been a feature of military discipline since the dawn of war. What is surprising is the number of ways armies have found to hurt their own men.

From the early days of Rome, discipline was strictly enforced within its armies. This became stronger as the military became more professional during the late republic and the empire. The use of caning is reported in 14 AD and was clearly no novelty then.

The Romans’ Byzantine successors adopted their violent tendencies and recorded them in a military manual called the Strategikon. During drills, officers walked along the back of the ranks carrying long staffs with which to hit anyone who spoke or who left his place. Centurions carried cane vines called vitis, which left scars on the backs of the undisciplined.

These scars were matched by those of the whips used in 18th-century European fleets. Many sea shanties record the pain of such discipline, and the British navy was famous motivated by rum and the lash.

The Death Penalty

Like beatings, military executions have taken many forms down the years. Roman sentries found asleep at their posts were clubbed to death by their comrades. This acted as a form of discipline for the whole unit. By taking part in killing their comrade, the remaining soldiers were reminded of what was at stake for them, and of the fact that their lives had been put at risk by his failure.

Punishment for fleeing a battle was more imaginatively terrible. To make clear the importance of their failing, legionaries found guilty of this cowardice received punishments normally reserved for the lowest classes of criminals – being thrown to wild beasts or crucified. Public display again ensured that the message reached far and wide.

Execution remained a common punishment long after Rome had fallen. Sometimes this punishment took place after a court-marshal, but at other times, such as during the rule of Soviet political commissars, it could take place in the heat of the action. At Canterbury in 1755, James Wolfe ordered his officers to immediately execute any man who quit his position, saying that “a soldier does not deserve to live who won’t fight for his king and country.”

The British army executed 346 of its own soldiers during the First World War, many of them men whose minds had been broken by their experiences and who had fled suffering what we would now regard as mental illnesses. But following the war, support for the death penalty for desertion waned, and it was abolished in Britain in 1930. The United States executed one man for desertion in World War Two, the unfortunate Private Eddie D. Slovik. More brutal regimes in Germany and Russia commonly used such punishments throughout the war.

Decimation

The Romans were unusual in using the death penalty not just to punish individuals, but to punish whole units. The word “decimation” originally referred to their punishment for units that shamed themselves by fleeing the battlefield. Lots were drawn within the unit, selecting one soldier in ten to be executed.

The rest were forced to sleep outside the army camp, where they would not receive the protection of its walls, and where their shame would be visible to the rest of the soldiers. Even their food rations were worsened, with barley replacing wheat.

Flaying

We usually think of military discipline as something inflicted on one’s own troops, but during rebellions and civil wars, the line between disobedience and being on the other side is a blurry one. Rebels are often treated brutally, none more so than the victims of Assyrian King Ashurnasirpal II.

Fighting to suppress revolts around the Euphrates, Ashurnasirpal indulged in frequent brutality to prevent future rebellions. Men who had failed him faced hideous punishment alongside rebel leaders. Their skins were flayed from their bodies and publically displayed, hanging from walls or decorating pillars erected specially for the occasion outside the gates of cities. Disobedient chieftains and royal officers faced equally terrible mutilation, with their genitals being chopped off.

Prussian Extremes

Though less consistently hideous than King Ashurnasirpal II, Frederick the Great of Prussia was perhaps the greatest example of a commander both obsessed with discipline and imaginative in the ways he executed it. He believed that the only way to ensure a well-run army was that “the common soldier must fear his officer more than the enemy”, and set up a regime designed to this end.

Some Prussian punishments were the same as those used elsewhere in the world, including death by hanging or firing squad. There were also beatings though these were made more unusual by the form they took. Two ranks of soldiers were assembled and the offender was made to walk between them, being lashed by each man as he passed.

A more modern-looking punishment was to sentence soldiers to exhausting exercise. This was taken to extremes, with the offenders having to complete 36 runs in three days, a hardship which killed most of them.

Strangest was “riding the wooden horse”. A wooden horse with a sharply pointed back was set up, and the offender was forced to sit upon it. Weights were sometimes tied to his legs, pulling delicate parts of his body down hard on the sharp, unyielding frame.