For the inhabitants of the west coast of the United States, the first months of 1942 were filled with paranoia. The sudden and ruthless attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, unleashed a wave of panic among the population of San Francisco and Los Angeles because of the real risk of a Japanese invasion.

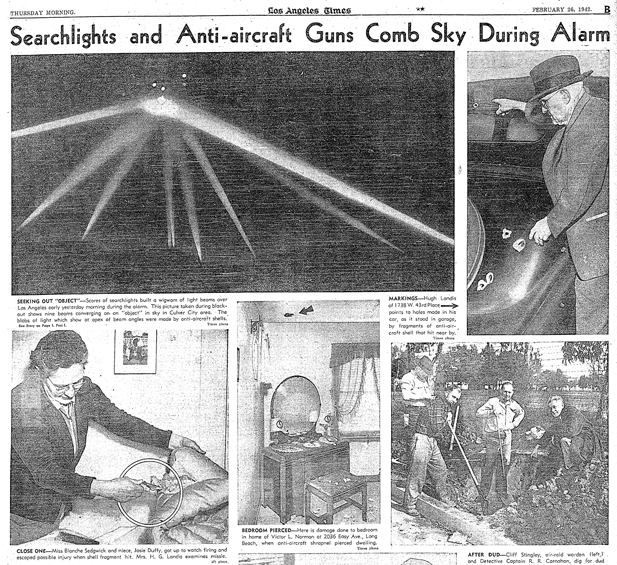

As if that were not enough, on February 24 and 25, 1942, the inhabitants of Los Angeles witnessed an event that even today continues to be surrounded by mystery: The Great Los Angeles Air Raid.

How to protect the west coast?

These events proved that the West Coast needed to be watched in anticipation of new attacks like Pearl Harbor. However, the west coast is 20,000 kilometers long, so protecting it properly would require a large number of ships and aircraft, as well as a phenomenal amount of fuel.

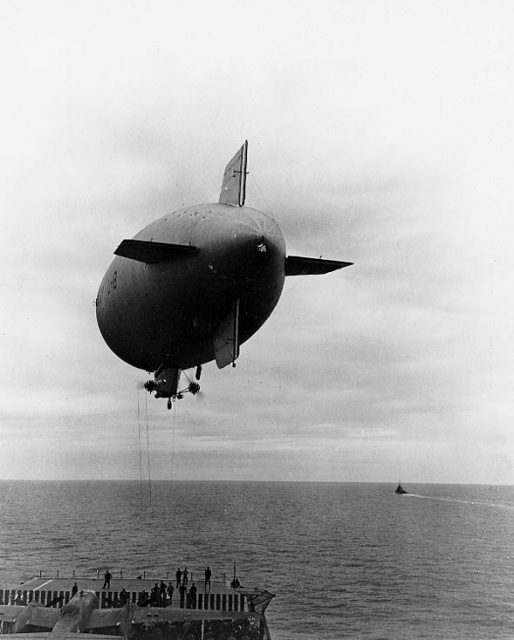

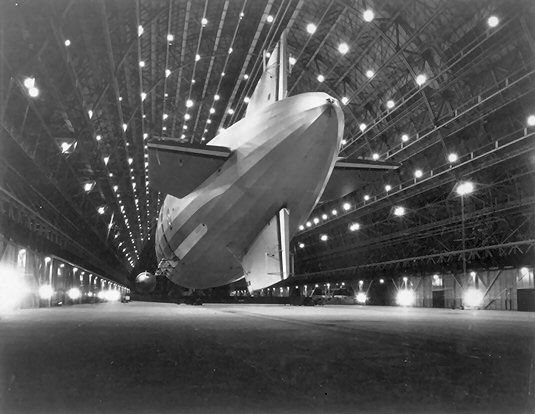

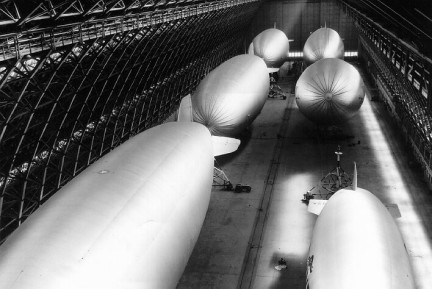

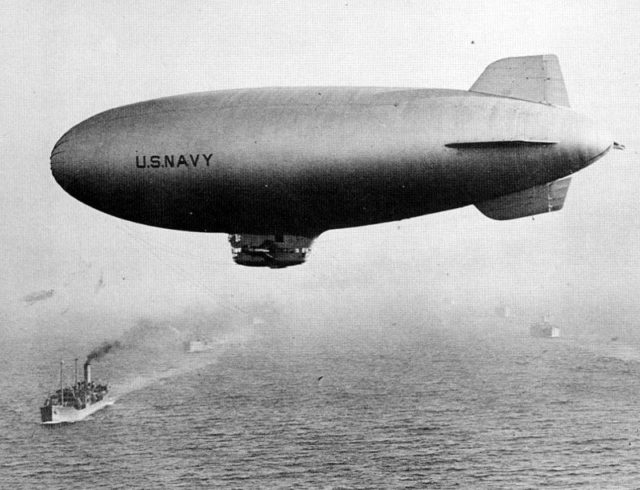

The United States Navy (U.S. Navy) quickly came up with a solution: dirigibles. Also known as “blimps,” these vessels were deemed best to carry out such observations.

The Best Choice: Dirigibles – Blimps

Due to the fate of the USS Akron, the USS Macon, and the Hindenburg, these magnificent but unfortunate airships had been relegated to being advertising mediums. However, thanks to their ability to remain in one spot for long periods, they were the perfect airships to search for Japanese submarines.

The contribution of the Goodyear Company

The U.S. Navy had few helium blimps at that time. Fortunately, the Goodyear Company assisted them by providing their blimps. The airships supplied by Goodyear included the protagonist of this mysterious story, an old class L advertising blimp, which was assigned to Squadron 32 (ZP-32) with headquarters in the base of Moffet Field, in California.

https://youtu.be/ROEON_LWebA

An easy mission

The L-8 blimp was given a routine anti-submarine patrol along the coast of California. The route it would follow was from Treasure Island to the Farallon Islands, then to Point Reyes, and finally to the south towards Montara. From there, it would proceed back to Treasure Island. The mission would last approximately four and a half hours.

On the morning of Sunday, August 16th, 1942, the L-8 took off from Treasure Island Airfield in the San Francisco Bay. The crew consisted of two men: the pilot was Lieutenant Ernest Dewitt Cody and he was accompanied by Ensign Charles Ellis Adams.

Everything was proceeding as normal

The L-8 left Treasure Island at six in the morning. At about 7:40 am, the crew made their last communication with the base, reporting that they were investigating an oil slick five miles east of the Farrallon Islands. For just over an hour, the airship explored the area in circles — something which was witnessed by the crews of two passing ships, namely a fishing vessel called Daisy Gray, and a Liberty-class armored freighter, the SS Albert Gallatin.

These crews thought that the L-8 was possibly looking for enemy submarines. It was flying low and, fearing that the L-8 would launch depth charges, the fishermen tried to gather up their nets and get away. However, the airship ascended without apparent incident.

The mystery begins

Around 10:30 am, the base tried to contact the airship, but without success. It was later sighted by planes and boats, neither of which noticed anything out of the ordinary. The last person to see it at 11:00 a.m. was an army pilot, who indicated that everything seemed normal. Shortly after that, the airship reappeared near the coastal highway between San Mateo and San Francisco, but now it was partially deflated.

Shortly after that, the airship began flying at very low altitude. It seemed to be aimlessly pushed by the wind. The L-8 came down at a nearby golf course (San Francisco’s exclusive Olympic Club). It hit the ground and bounced several times, causing damage and dropping a depth charge. Then a sudden gust of wind made it rise once more and enter the streets of Daly City, just 15 miles (about 24 kilometers) from San Francisco. After hitting several roofs and electrical wires, it ended up crashing on Bellevue Avenue.

Nobody on board

The first person to arrive at the scene of the accident was William Morris, a volunteer fireman who lived just opposite where the airship had crashed. He ran to help the crew and was surprised to see that the gondola door was open and nobody was in the cabin.

Immediately, the Daly City fire brigade, with the help of numerous spontaneous collaborators, began to look for the crew. They followed the path the L-8 had taken since it had come ashore and even ripped the balloon apart in case somehow the crew had been trapped inside.

Everything in order inside the gondola

Inside the gondola, everything seemed to be in order. The code and signs books were in place, as well as the parachutes, the emergency raft, the weapons, and the remaining depth charges. The radio equipment and the external speakers worked perfectly.

Even some classified documents that Cody had taken on board were still there. Only the lifejackets were missing, but it was common for the crew to wear them. The U.S. Navy withdrew the airship just hours later and organized a meticulous search for the crew along the coast, but without yielding any results.

The investigation

Two days later, a committee was formed to try and clarify the circumstances surrounding the disappearance of the two crew members. The following scenarios were considered.

There might have been a malfunction with the L-8. However, the maintenance staff stated that all the airship systems worked perfectly, including the radio. The crews of the ships who had seen the L-8 out on patrol declared that it had been flying normally and showed no signs of having problems.

Next bad weather was considered, but this idea was dismissed since the morning had been calm, with some fog, but no rain or strong winds.

The hypothesis was put forward that there had been a stowaway who had hidden inside the airship and killed the two men. This idea, too, was discarded quickly. Firstly, the stowaway would have had to overcome the security of the base, and secondly, his presence would have been evident due to the weight gain in the airship.

The work of a spy was considered, but the airship was a low-value target and didn’t appear to justify such action.

Perhaps there had been a fight between the two men, but Cody and Adams were friends, and there was no reason to think that they could hate each other enough to want to kill one another. Nevertheless, this hypothesis was analyzed, but nothing could be proved.

The hypothesis that they had fallen into the sea seemed most likely since the airship doors had been open. However, should one of them have accidentally fallen into the water while they were checking the oil slick in the Farallon, it did not make sense that his partner did not report this event to the base.

It was unlikely that they fell simultaneously and besides, neither of the two boats nearby had reported seeing anything or anyone falling from the ship. Furthermore, the blimp doors had a special locking system to prevent accidents.

Without results

The U.S. Navy concluded that both men had disappeared for unknown reasons. An accidental fall was seen as the most likely cause, even though there was not enough evidence to reach any definitive conclusion. Their names were included in the list of missing in combat, and a year later they were officially declared dead.

A long time has passed since this event, but the fate of Lieutenant Cody and Ensign Adams remains unknown. Perhaps they were kidnapped by the Japanese, abducted by UFOs, or maybe they did just fall into the sea.

Read another story from us: This Tragedy At Sea Still A Mystery

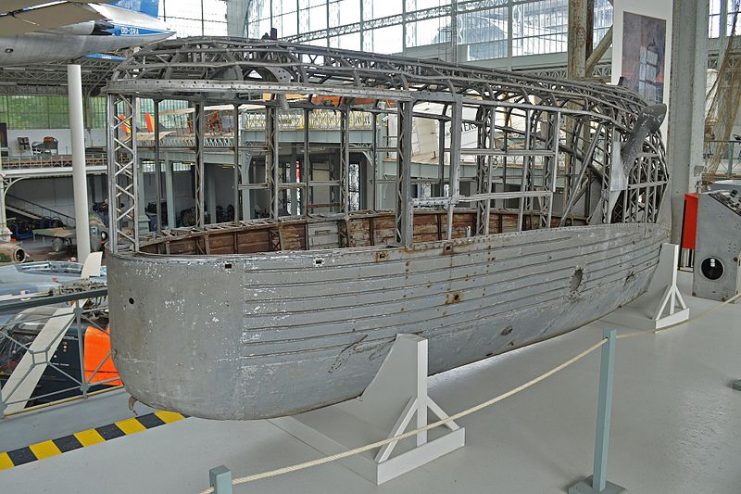

On the other hand, the L-8 had a better destiny. It was repaired and continued carrying out missions until the end of the war. Subsequently, the U.S. Navy returned it to Goodyear, which used it for sports broadcasts until 1982. Its gondola is currently exhibited at the National Museum of Naval Aviation in Pensacola, Florida.