It began with the taking of eight British civilian hostages in a faraway country about which most people in Britain knew nothing and cared less.

By the time it was over, a king lay dead by his own hand. A multi-national force had marched an 800-mile round trip through the interior of Eastern Africa, dropped off from their home base in Bombay by an armada of ships numbering in the hundreds. The power of the British Empire to protect its people, and its interests, had been displayed loud and clear.

The Abyssinian Expedition of 1868 was unlike any military campaign before or since.

Today, the idea that an entire expeditionary force could be raised to invade a country on another continent and just to rescue eight people might seem unthinkable; however, that is what happened as a matter of course at the height of the Victorian age.

The scale of the British Empire in the 1800s is truly astounding. In 1851, the population of Great Britain and Ireland was numbered at 20,959,477 (a little less than a third of what it is today), or roughly 1.6% of the world’s population.

However, the British Empire at its peak included 11.5 million square miles of territory (home to fully 25% of the world’s population), not to mention the very real hegemony that it held over the world’s oceans. This control of the seas was made possible by the fact that the Royal Navy was maintained to be larger than the combined naval strength of any two other nations.

British banks had more assets and currency on deposit than all of the rest of the world’s banks put together, and two-thirds of the world’s shipping and one-third of all of its trade passed through the British economy.

In an age before oil became the main source of global energy, coal provided the fuel for industry and trade, and half of the world’s coal came from Britain, along with half of its iron also. It was a time of confidence and almost unlimited horizons, bred by economic dominance and cultural assuredness.

Though the Crimean War of the early 1850’s has been held to be a disaster for the British Army, the war ultimately ended with an Allied victory. The Empire of the middle 19th century still had the potential to project its power effectively on a global scale, to a degree that remains unprecedented, even with all of the technological achievements that have been made up to the present day.

Britain had recently defeated China in the Second Opium War, and the British Army occupied Beijing in 1860. In 1876, Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli was confident enough of British rule over the Indian sub-continent that he arranged to have Queen Victoria crowned the “Empress of India”.

From the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815 to the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, the Empire dealt with military threats all along its vast and expansive borders, from the mountains of Nepal and Tibet across to the Afghan border and all along the African coast and into the continent’s interior.

One of these actions, the 1896 conflict with Zanzibar, remains the shortest “official” war on record, as the Zanzibarian surrender came after just 38 minutes of fighting.

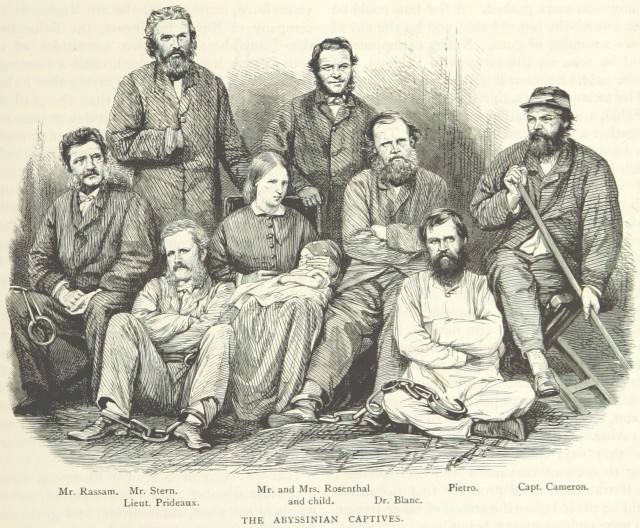

The initial steps of the conflict that would lead to the Abyssinian Expedition took place in 1867, when the King of Abyssinia (now Ethiopia), Tewodros II, imprisoned a British missionary named Henry Stern and his assistant, who went by the name of Rosenthal.

Both men were chained and beaten, and when the British Consul to the area and another party of missionaries attempted to have the men released, they were arrested in turn.

Two British diplomats were then dispatched to have these hostages released, but they were also imprisoned on the king’s orders.

The British Captives in Abyssinia.Tewodros had formerly been an ally of the British, and he had fostered friendly relations with all the major European nations during the early stages of his reign. He was proud of his status as the only Christian monarch in Africa, as well as the fact that Ethiopia alone among the African nations remained free from western colonization.

His early reign had been marked by consolidation, liberalism, and the rule of law; however, as time went by, Tewodros succumbed to megalomania and paranoia, and his subjects rebelled against him.

At the time he took the British subjects hostage, he had already declared himself the direct descendant of the biblical King Solomon and was prone to giving audiences on his throne while surrounded by lions.

It became apparent to the British that all avenues of negotiation were closed and that overt action would have to be taken. After a final written appeal to Tewodros by the Queen had been ignored, Victoria sent a message by the newly installed international telegraph system to the Lieutenant-General Sir Robert Napier in India. Her order was stark: “Break the chains.”

After a final written appeal to Tewodros by the Queen had been ignored, Victoria sent a message by the newly installed international telegraph system to the Lieutenant-General Sir Robert Napier in India. Her order was stark: “Break the chains.”

Napier, a veteran of the Indian Mutiny and the Chinese war, was unenthusiastic about the mission, but he was also stoic about his duty and the necessity not to yield to threats or force, “The expedition would be very expensive and troublesome… Still, if these poor people are murdered, or detained, I suppose we must do something,” he is quoted as saying.

When fighting in the North-West frontier of what is now Pakistan and Afghanistan, Napier had adopted as his troops’ motto the phrase, “Never Give Way to Barbarians”; now, he used the Latinized form of the Queen’s message as his watchwords, “Tu Fincula Frange” – break the chains.

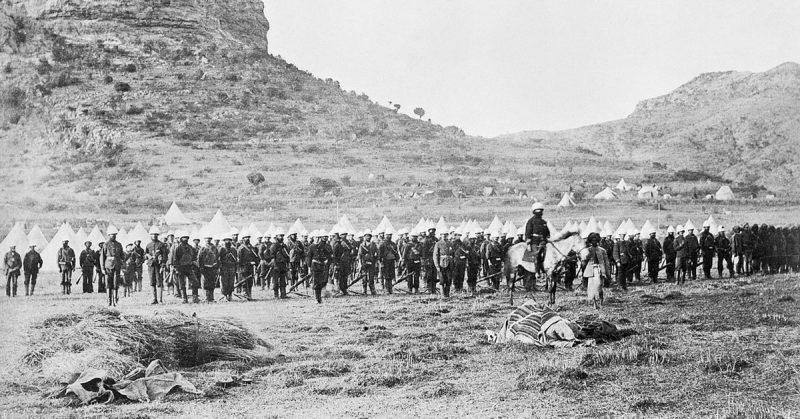

With a flotilla of 280 steam and sail ships, the Royal Navy ferried Napier’s army from Bombay to the port of Zula, about 25 miles south of Mosawah, on the Red Sea coast. The expeditionary force was a wonder of technological, military, and cultural proportions.

In addition to 7,000 camels and 13,000 mules and donkeys, the army marched with 44 Indian elephants and 7,000 bullocks. The ranks themselves were made up of five squadrons of cavalry, ten regiments of infantry, four batteries of field and horse artillery, six 5½ inch and two 8 inch mortars, all in all, 13,000 British and Indian soldiers and 26,000 logistical support staff.

To make sure that all of the necessary men and equipment were landed safely, Napier brought along an artificial harbor, as well as lighthouses and a mobile railway system.

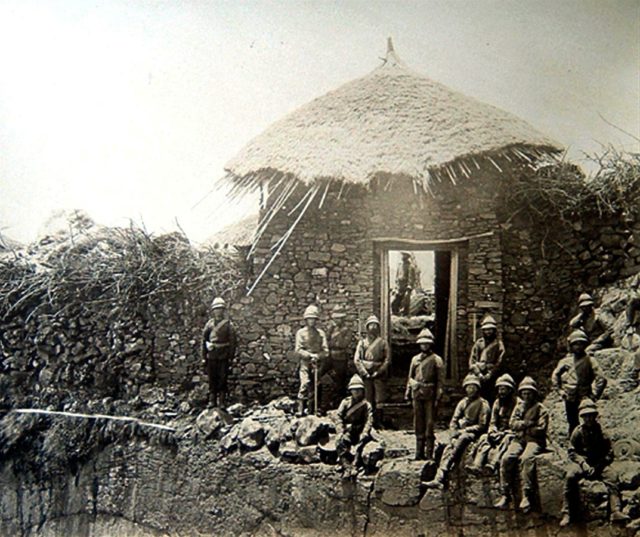

In the meantime, King Tewodros had heard about the approaching force and withdrawn with his hostages to a mountain fortress deep in the Ethiopian desert interior.

The fortress, Magdala, was a full 400 miles from Napier’s starting point at Zula. The British would not only have to contend with the climate and the possibility of attacks from native tribes, but they would also face the strain of crossing the arduous scrub and mountain passes, where pulleys and ropes would be necessary to move heavy equipment and animals.

Undeterred, Napier set off with his veritable military menagerie through the heat and humidity of the season. It was vital that they make good time on the march, or else they would be caught by the torrential downpours of the summer rains later in the year.

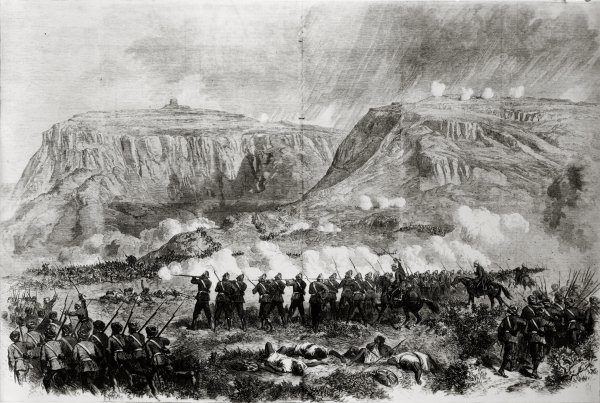

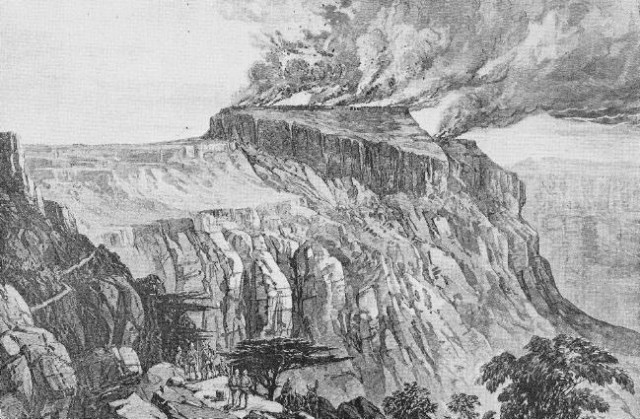

Three months later and with countless dead pack animals left behind, the British force emerged like a nightmarish mirage at the foot of Magdala and began deploying into battle formation. Immediately, the attack began with artillery, rocket and mortar fire, and the full force of both ancient and modern weaponry was put into effect.

The British carried modern breech-loading rifles with fixed bayonets. The enemy was outgunned by a large margin,

Nevertheless, the Ethiopians made the initial charge down the mountain. They were held off and pushed back by the 4th King’s Own Regiment. The Highland Scottish “Black Watch” Regiment (motto: “No one attacks me with impunity”) and the West Riding Regiment were the first up the hill to lead the counterattack and charge the Ethiopian forces in turn.

Alongside the braying of elephants, the screaming of mortars, and the din of regimental bagpipes, a seasonal thunderstorm swept over the combatants in the midst of the battle, drenching all and adding to the general apocalyptic mood.

By the battle’s end, all eight of the British captives were free, Magdala was burned, and Tewodros had shot himself in the head with a British made pistol that, legend has it, was, in happier times, a gift from Queen Victoria. Ethiopian dead were numbered at 700, with another 1,400 wounded, while the British losses were put at just two dead and 18 wounded.

Magdala was burned and razed, and Napier’s army turned and marched back once more to Zula, with their regimental bands playing all the way. They set sail from their pre-fabricated harbor on the return journey to Bombay.

Australian-born writer Alan Moorehead observed of the Abyssinian Expedition that “There has never been in modern times a colonial campaign quite like the British expedition to Ethiopia in 1868. It proceeds from first to last with the decorum and heavy inevitability of a Victorian state banquet, complete with ponderous speeches at the end. And yet it was a fearsome undertaking; for hundreds of years the country had never been invaded, and the savage nature of the terrain alone was enough to promote failure.”

The choice of Napier, an officer of the Royal Engineers rather than one of the corps more traditionally associated with offensive expeditions, was an inspired decision, as his steadfast leadership both of the initial landings and the grueling 400-mile march to Magdala was flawless. His army suffered none of the unnecessary deaths that the British Armies in the Crimea had suffered.

When news of the victory reached London, the reaction was jubilant, and there was a real sense of satisfaction that the national prestige and good name had been maintained in so professional and stalwart a manner. The Pall Mall Gazette published the following on July 4th, 1868 –

Sir Robert Napier returned to London today (Thursday) from his Abyssinian campaign, and there is no reason to fear that he will have cause to complain of any sort of deficiency in his reception. Personally: he deserves all that he will receive. It is long since any English general has met with such unqualified success or executed so thoroughly the task which was entrusted to him. He deserves all the congratulations and honors which are the appropriate reward of great skill, thoroughly sound judgment and that sort of good fortune which seldom, if ever, befalls those who do not deserve it. Something, moreover, may properly be given, not only to Sir Robert Napier personally but to the nation at large. There can be no doubt that, taken as a whole, the Abyssinian expedition has been creditable to England. It has given a clear demonstration of several facts which it is highly important for all persons whom they may concern to bear in mind. It has read a lesson to barbarous Powers as to the far-reaching and irresistible powers of civilization which they are not likely to forget, and it has shown that the English nation, in particular, is prepared, in case of need, to make great efforts for the punishment of an insult, or the protection of persons entitled to its protection.

It is probably true that we have made an investment in the way of prestige which is worth its cost, though such investments are certainly hazardous and uncertain; we have also performed a military exploit the importance of which our continental critics seem inclined to exaggerate, but which most assuredly proves to demonstration, if anybody is inclined to doubt it, that when the military spirit of this country is fairly roused and has time to produce its full effects, it is a very formidable power indeed, and can be supported by resources which are practically almost unlimited. These considerations are connected in a sufficiently obvious, but also in a perfectly legitimate, manner with Sir Robert Napier’s return to receive the well-merited honors which await his return.

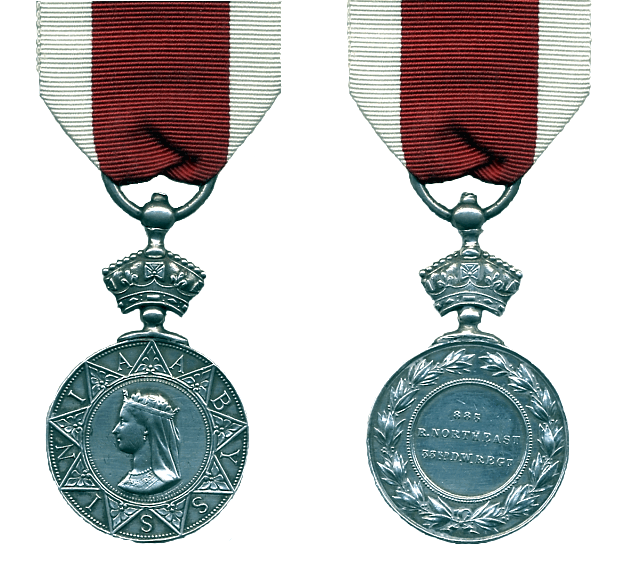

For his service, Napier was subsequently granted a peerage to become Robert Napier, 1st Baron Napier of Magdala, and his statue still stands in the Viceregal residence at Barrackpore.