Google Maps makes it perfectly clear that you should take its directions with a grain of salt and a hefty dose of common sense. The problem is that some people ignore that caveat with disastrous consequences.

In 2007, for example, someone in Britain ignored road signs in favor of Google Maps – which is how they ended up in the River Sence. Two years later, Lauren Rosenberg made international headlines by being so determined to follow Google Maps to the letter that she walked directly into oncoming traffic and was hit. Rather than blame herself, however, she pointed a finger at Google.

The following year, Nicaragua took a page from Rosenberg and blamed Google Maps for its invasion of Costa Rica.

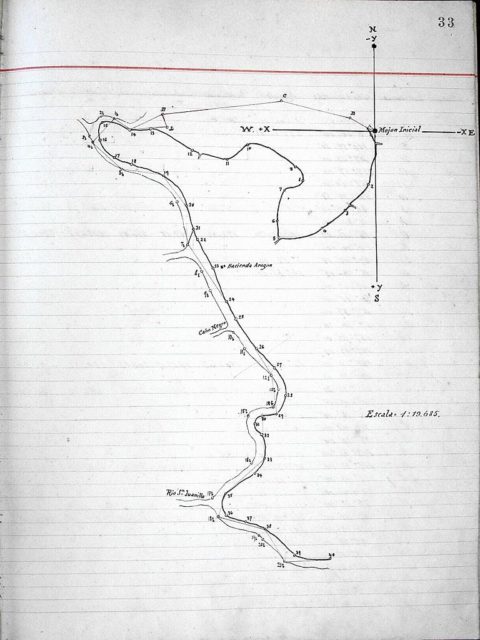

Nicaragua and Costa Rica were once part of the Spanish Empire. But when the latter declined and the two became independent, they clashed over territory. To end it, they tentatively agreed to make the Rio San Juan the dividing line between their east-west borders.

To settle the issue, US President Grover Cleveland reaffirmed the Cañas-Jerez Treaty of 1858. Further upheld by the Central American Court of Justice (CACJ) in 1916, the treaty gave the Rio San Juan to Nicaragua, but allowed Costa Rica to use it for trade without taxation.

In 1998, however, Nicaragua banned the Costa Rican police and military from using the river and imposed a US$25 tax on Costa Rican tourists. The International Court of Justice (ICJ) got involved the following year by supporting Nicaragua’s ban on its neighbor’s police and military, but not its tourist tax. It should have ended there, but it didn’t.

Enter Edén Atanacio Pastora Gómez (“Edén Pastora,” for short) – a member of the Sandinista National Liberation Front (SNLF). He later quit that group and ran for Nicaragua’s presidential elections in 2006.

Gómez lost to José Daniel Ortega Saavedra – who’s still Nicaragua’s president as of 2016. To keep him busy, President Ortega appointed Pastora to the position of Minister of Development of the Rio San Juan Basin. Given Pastora’s guerilla past, it was a recipe for disaster.

Because on October 8, 2010 Pastora led soldiers onto Isla Calero – a 1.86-mile long island that serves as a wetland ecological reserve with protected environmental status. But there was a problem.

Isla Calero belongs to Costa Rica. And to make sure that everyone knew it, the Costa Ricans had very graciously put their flag on it. Seeing it, Pastora very ungraciously took it down and replaced it with Nicaragua’s flag.

That done, he ordered the island’s trees removed to make way for dredging operations that would clear a channel to the Caribbean Sea. And where was the dredged material to go? Why, on the island, of course.

Costa Rica was understandably upset and complained to Nicaragua. Hoping to de-escalate the tension, Pastora and his men left the island, but Ortega had other ideas.

He denied the charges, but when confronted with the evidence, claimed there was no way Pastora could possibly have invaded Isla Calero. Why? Well, because the island was obviously Nicaraguan territory!

Costa Rica’s reply came on October 22 when they sent 70 police officers to the border. Nicaragua responded by sending over 50 soldiers to “their” island.

So how did Pastora justify his actions? Google Maps. In 2010, Google put the Nicaraguan border about a mile and a half into Costa Rican territory – effectively placing Isla Calero within Nicaraguan jurisdiction.

Google Latin America apologized profusely, but claimed that Google Maps was a work in progress meant to help people get from point A to B, as well as find their nearest taco joint. Period. It was never meant to justify invasion, or as Google more delicately put it – “to decide military actions between two countries.”

The company then updated the information and the correct border can still be seen on current maps. End of story, right?

Wrong. In response to the company’s statement and subsequent correction, Pastora changed his story. His new version claimed that he had never relied on Google Maps to begin with and accused the Nicaraguan press of misquoting him.

Pastora insisted that he had instead relied on the original text of the 1858 Cañas-Jerez Treaty. Except that the treaty’s original text supports Costa Rica’s claim to Isla Calero. Ditto with President Cleveland’s interpretation and the later one by the CACJ. Up till then, even Nicaraguan maps recognized the island to be Costa Rica’s.

Faced with that inconvenient tidbit, Ortega came up with an ingenious answer. Costa Rica’s border had been moving steadily north for centuries as the San Juan River delta slowly dried up – which is certainly true.

As such, Costa Rica had been slowly occupying Nicaraguan land. Pastora was therefore simply recovering territory based on how the San Juan River had once flowed… over 150 years ago, that is.

Costa Rica wasn’t buying it and demanded resolution from the Organization of American States (OAS). Nicaragua refused and wanted the ICJ to arbitrate. The OAS ordered both countries to remove their troops from the area while the issue was resolved.

Costa Rica agreed, but Ortega refused because he was hoping to get reelected on a patriotic vote. It worked. He was reelected and in February 2011, the Nicaraguan Institute of Territorial Studies published a new map placing Isla Calero within Nicaragua.

Tensions rose as Nicaragua built a fence on the island and cut channels into it. Costa Rica responded by building a highway next to the river on territory also recognized as protected wildland. Fortunately, despite increased militarization on both sides, no fighting actually broke out save for a few civilian skirmishes.

In the end, Costa Rica won. Well, sort of. The ICJ got involved, ruling against Nicaragua on December 16, 2015. Before it could rejoice, however, Costa Rica was also reprimanded for building their road.

On June 7, 2016 Costa Rica demanded US$6 million in compensation for its damaged island. The ICJ agreed, but there’s another problem – it has no power to make Nicaragua pay.

And since Ortega is up for another reelection… well, we know how that turned out the first time, don’t we?