Hostilities in the Nigerian civil war commenced on the 6th day of June 1967; it is one of the sourest conflicts ever to (dis)grace the record books of African history. Spanning a gruesome thirty months of cascading bloodletting, massive starvation, and disease outbreaks, memories of those days still haunt those who survived.

“I will take these memories to my grave,” says Mr. Kanayo, who lost a leg during a shell attack on a gloomy night while he was hiding in the forests taking a brief rest after running all day.

The declaration of ‘no victor, no vanquished’, and the ultimate cessation of gunfire between the secessionist state of Biafra and the Nigerian government brought forth a tremor of relief across the continent, particularly among the people from Biafra who had agreed to be called Nigerians again. Survivors walked to whatever was left of their home glad that it was finally over. They were willing to start over again, to build again, from the rubble and ashes of war.

What lessons have Nigerians learned from their tainted history since their independence celebrations in the 1960s?

A peek into the past should be enough for Nigeria’s younger generations to witness the rage of the storm that wrecked their country, how far they’ve come since then, and how much they need to do to keep their dear country from degenerating into a wasteland.

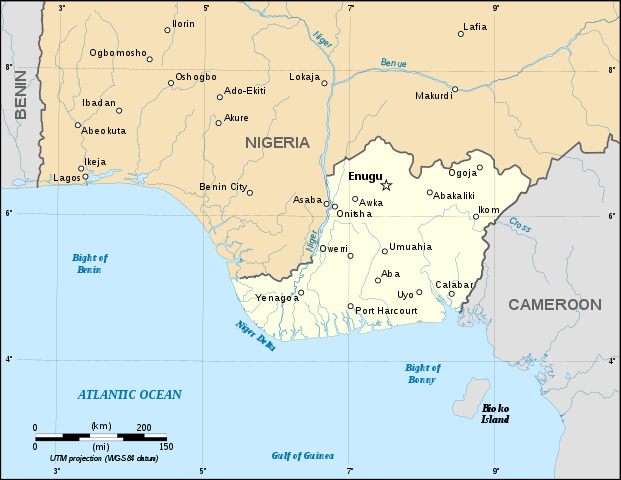

Nigeria is a country of more than 100 million citizens. Being crowned the largest black nation on the planet, she is made up of three major ethnic groups: the Igbos, who reside in the South Eastern part, the Hausas of the northern region, and the Yoruba group which resides in the southwest regions.

In between these groups are a number of minority tribes. After being merged into one by its British colonial masters, Nigeria was declared to be an independent, sovereign state. Unbeknownst to them, it was the start of unimaginable gloom.

After the independence of Nigeria, a series of crises began to surface due to the nepotism, tribalism, and corruption now rife in the young nation. These crises escalated dramatically after the military coup of January 15, 1966, which saw the installation of Major-General Aguiyi Ironsi from the Igbo group as Nigeria’s first Military head of state.

Ironsi appointed military governors over the Northern, Western, and Eastern Provinces, with the infamous Lt-Col. Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu appointed in charge of the Eastern Provinces.

During the coup d’état of January 15, 1966, Sir Ahmadu Bello, who then was the Sardauna of Sokoto State and Premier of the Northern Region, was murdered. Accompanying his death was the murder of Sir Abubakar Tafawa Balewa, who was the federal prime minister and a Northerner.

Four other Northern officers were killed as well as two Western and one Eastern officer. The ethnic distribution of these deaths brought about the allegation that the coup was plotted mainly to benefit the Igbos.

On 29th July 1966, a counter-coup occurred. This resulted in the death of Aguiyi Ironsi and thirty-three other officers who were from the Eastern Region. At the end of the coup, General Yakubu Gowon became the new head of state.

Closely following this event was a series of riots in the Northern Region in which thousands of Easterners in the north were murdered. Retaliation ensued in the east, killing scores of Northerners residing there. This string of incidents saw the return of about a million Eastern refugees from all corners of the federation and the expulsion of non-Easterners. This worsened as the massive movement polarized the crisis into an Eastern Region—Federal Government conflict.

In 1967, the Nigerian Supreme Council held a meeting at Aburi, Ghana. Some agreements were supposedly reached but chaos resumed when it was clear that both the Federal Government and the Eastern Region interpreted these agreements differently. Several other attempts at reconciliation failed.

The gloom would get gloomier on the 27th day of May when General Gowon publicized a decree dividing Nigeria into twelve states. On the 30th day of May, Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu declared the secession of the Eastern Region and the subsequent declaration of the Independent Republic of Biafra.

The Federal Government would not allow this, and Biafra was determined to break free. Then, on the 6th day of June 1966, the Nigerian Civil war began.

During the two and half years of the civil war that followed, sometimes known as The Biafran War, about 100,000 military casualties were recorded. About 2 million Biafran civilians (mostly children) died of starvation.

The civil war was argued by many to be genocide. One of the more prominent demonstrators of this claim was Bruce Mayrock, a student at Columbia University. He had set himself ablaze in front of the UN headquarters to protest the killing of Biafrans after claiming that all his appeals to the UN were being ignored.

On the 12th of January 1970, the war was finally declared over. Relative peace was slowly breezing in as days turned to years and years into decades until all that was left were haunting memories. The effect of the war is still evident everywhere. And just like Mr. Kanayo, so many Nigerians will take these memories to their graves.