Joseph Stalin once said: “The death of a man is a tragedy. The death of a million is a statistic.” Sadly, history seems to have proved the paranoid dictator correct.

Perhaps the statement has some truth to it because the average human mind is incapable of grasping the totality of a million or more deaths.

Of course, we are sad when we hear of a tragedy, either natural or man-made, but when we talk of the deaths of millions of people, the human soul perhaps has to steel itself against the horror of a million deaths, or else we could not function.

Joseph Stalin was a man who knew about death. He caused millions of them himself, and his nation suffered an estimated twenty million or more deaths during the war with Hitler’s Germany.

Though people in the West knew this, the Cold War somehow seemed to blunt the impact of this figure or move it to the background. Today, though the West and Russia are now locked in a new Cold War, the average informed person knows that the Soviet Union suffered more losses than any other nation in World War II.

However, it is interesting to note that many well-informed people are not aware that China’s conflict with Japan cost at least ten million lives, far more than any other nation except the USSR.

Shortly after WWII, the Chinese Communists took over, and China went from being a friend to the West to a mortal enemy. The monumental casualties sustained by that nation took a back page – in the West, at least.

Like those in the Soviet Union, the losses in China were mostly civilians. According to the Oxford Companion to WWII, Chinese Nationalist losses amounted to about two million.

But these estimates are based on official Nationalist figures and they are considered highly suspect: in the chaos of WWII China, any exact figures are hard to come by. The two million are likely to be those who were officially logged at the time – not including those MIA, etc.

Of course, the Chinese were fighting not only the Japanese but each other in a civil war which had been raging since the early 1930s.

Though temporary truces took place between the Nationalist forces of Chiang Kai-shek and the Communists under Mao Zedong, the death toll from the internecine Chinese fighting easily numbers over one million as well – likely far more.

Many different academic studies have been done surrounding the deaths in China. They are hampered by a number of things: the lack of or poorly recorded data due to the rural, decentralized, and somewhat backward nature of China at the time, political considerations and pressure, the chaos of war, and so on.

What we do know is that the war in China was unbelievably savage. Civil wars always are. But in addition, there were the Japanese.

The fascist military government of Japan and governments before that had sponsored the idea of Japanese cultural and ethnic superiority. Though this feeling of superiority extended to virtually all of Japan’s enemies, whether they were European or Asian, China was particularly singled out.

The reasons for this sentiment have taken up volumes. Such sentiment existed at a time when Japan, beginning in the 1870s, had built itself from a feudal pre-industrial society into a world power in the span of just decades.

In 1896, the Japanese inflicted a serious defeat on China. Since then, it occupied (along with many European nations and the United States) various territorial “concessions” given by the weak Chinese governments of the time.

In 1904-5, the Japanese defeated Russia and became the dominant power in northeast Asia.

The unreal success of the Japanese military and its incredible economic changes helped to encourage feelings of ethnic superiority that had existed for centuries.

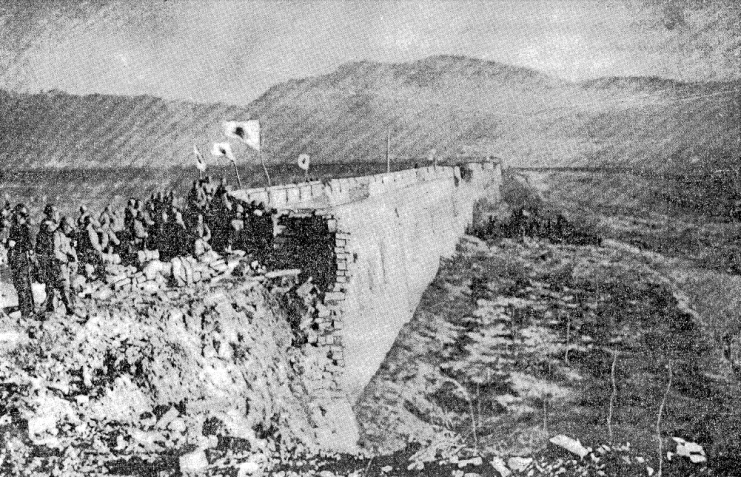

In 1931, the Japanese invaded the semi-autonomous Chinese territory of Manchuria against weak Chinese resistance, increasing the feeling of military and cultural superiority.

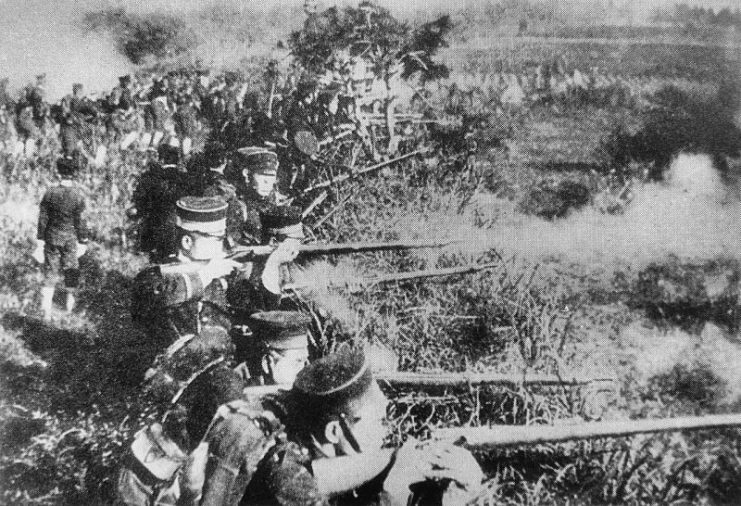

In 1937, the Japanese invaded China proper. Most War History Online readers will know of the “Rape of Nanjing,” which took place in the winter of 1937-38 and claimed an estimated 300,000 lives.

The story of Nanjing is a microcosm of what occurred all over western and coastal China during WWII. The event is named as it is because rape occurred on a mass scale. Those rapes were mostly followed by murder.

Horrible incidents including so-called “bayonet practice” on living people, the formation of mountains of bodies and skulls, officers “blooding” their samurai swords on dozens of men, women, and children a day… the list goes on in the most grisly way possible.

These types of things occurred throughout all parts of Japanese-occupied China. The tale of the Japanese occupation of China is in many ways less history and more horror movie.

And it gets worse. Official Japanese policy adhered to a grisly list known as “The Three Alls” which were: “Kill All, Burn All, Loot All.” This wasn’t a soldiers’ macabre saying – this was official Japanese military policy.

Though one is always hesitant to compare such monstrous crimes, the Germans tried to hide their genocide behind coded language and euphemism. The Japanese did not care – the Three Alls were orders to the military for all to see and hear.

Though the Japanese did not create killing centers such as those constructed by the Nazis, in many ways and in many instances murder became official Japanese policy.

Chemical weapons such as mustard gas and other agents were used by the Japanese in battle, and, even more atrociously, on human “guinea pigs” by a Japanese military command known as “Unit 516,” later known as “Unit 731.”

Unit 731 was the Japanese version of the horror show that went on in the so-called medical divisions of the Nazi death camps. Located near Harbin, in the north of China, Unit 731 deliberately spread plague, exposed people to gas and low temperatures, and performed medical experiments so evil and useless that they defy imagination.

Two examples among many will suffice: limbs were amputated and attached to other areas of the body, and animal blood was transfused into living human beings. Of course, the results of these experiments were an agonizing death.

Sadly, because the United States needed to ally with Japan as a bulwark in Asia against the threat posed by the Soviet Union, many of the worst criminals escaped justice.

When China became communist in 1949 and allied itself against the United States and its Japanese ally, the tragedy of WWII in China was pushed to the back pages in the history books – but not in China.

Anyone looking for a reason to explain the difficult relations between China and Japan today need only look back to 1931-45.