The Philippine Revolution against over three centuries of Spanish domination began with Andrés Bonifacio, leader of the Katipunan, a liberalist movement that sought independence for the Philippines from Spanish colonial rule.

The Katipunan was an offshoot from José Rizal’s La Liga Filipina, a movement that sought to bring about political reform in the colonial government of the Spanish. Rizal had been deported just after his organization was formed with their first meeting.

After a few years had passed with virtually no changes in the constitution, Bonifacio and others lost all hope of any peaceful reform being brought about by La Liga Filipina. Abandoning the organization altogether, they concentrated their efforts into the Katipunan to bring about a revolution with the use of violence and arms. The organization consisted of both male and female supporters, including Bonifacio’s wife, who led the female faction.

Bonifacio recognized the strategic importance of the city of Manila and resolved to take control of it, convinced that once he did the residents, being fed up with Spanish rule, would support his cause. However, this plan was foiled before it got off the ground as a result of a conflict between two Katipuneros, one of whom spilled the beans about the plot to the Spanish friars.

The traitor was one Mariano Gil who, along with other friars, had previously been trying to get the Spanish Governor to take action regarding his suspicions of a revolution.

Without concrete proof, the Governor merely saw their suggestions as accusations and could do nothing about it. The parish priest of Tondo reported his findings to the owner of the Diary de Manila, the printing press where the two Katipuneros worked, and on searching the place they found the paraphernalia used in printing Katipunan documents and other items proving the existence of the Katipunan, it was August 19, 1896.

A series of arrests of Katipuneros in Manila followed and several Filipinos were jailed or imprisoned. Amongst them were some wealthy and prominent Filipinos, some of whom were innocent.

Jose Rizal was tried and executed later at the old Bagumbayan field on December 30. With the hunt for Katipunan members still ongoing, Manila had become a dangerous place for them. As many as five hundred arrests had been made and many fled the city for fear of been captured, tortured or killed.

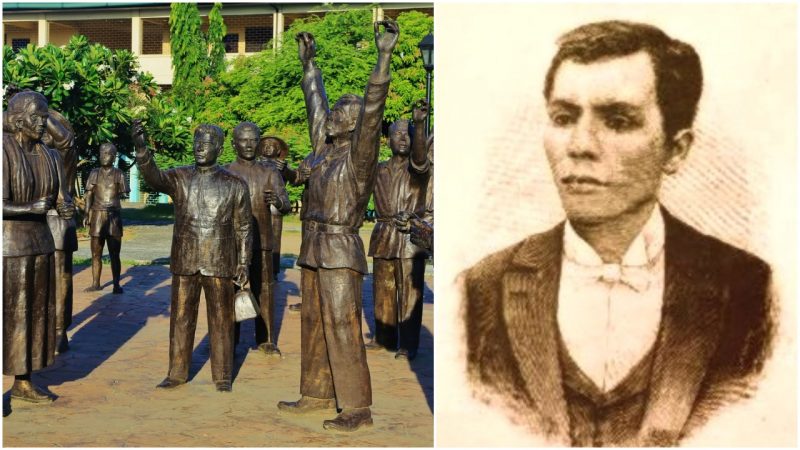

Bonifacio was not amongst those captured, however. He and many others had escaped to Pugadlawin, and in a meeting at the house of Juan Ramos on 23 August 1896, Bonifacio urged his followers to tear into pieces their Cédulas (residence certificates) as a sign of revolt against the Spanish government.

The men, highly motivated by the killings and arrest of their members in Manila, tore up the documents and let out the cry “Long live the Philippines,” which is known as the Cry of Pugadlawin in Philippine history.

It was decided that all their supporters in the surrounding towns be alerted of the impending strike on Manila which would take place on 29 August. To this effect, Bonifacio released a manifesto on the 28th:

“This manifesto is for all of you. It is absolutely necessary for us to stop at the earliest possible time the nameless oppressions being perpetrated on the sons of the people who are now suffering the brutal punishment and tortures in jails, and because of this please let all the brethren know that on Saturday, the revolution shall commence according to our agreement.

For this purpose, it is necessary for all towns to rise simultaneously and attack Manila at the same time. Anybody who obstructs this sacred ideal of the people will be considered a traitor and an enemy, except if he is ill or is not physically fit, in which case he shall be tried according to the regulation we have put in force.”

The first battle of the Philippine Revolution took place on 30 August 1896 at San Juan del Monte with a thousand men behind Andrés Bonifacio. On the eve of the 29th, they attacked civil guards present at San Felipe Neri, a city located east of Manila, who on seeing the mob surrendered their weapons and were taken captive.

The Katipuneros had little in the way of ammunition; generally equipped with bolo knives, they also had a few guns with them. By the early hours of the morning of the next day, Bonafacio’s army had been joined with two fresh groups of Katipuneros, about four hundred in number.

After gathering the weapons obtained from two successful encounters with civil guards, Bonifacio and his men began their attack on El Polvorin, a Spanish depot located in San Juan del Monte where they were met by Spanish Infantry and gunmen armed with German Mauser rifles.

However well armed this Spanish contingent was, they suffered the loss of two of their soldiers, one of whom was the commander in charge. This and the intimidating number of Katipuneros behind Bonifacio, who it seemed was always able to evade capture, caused them to retreat to the Manila Water Works Deposit office that was situated nearby while they awaited reinforcements.

The Kaptipuneros advanced towards the building in hopes of eliminating what was left of the Spanish resistance and claiming victory over San Juan Del Monte. It wasn’t long before shots of the 73rd Jolo regiment of Spanish cavalry, led by General Bernado Echaluce y Jauregui, struck the bodies of the Filipino comrades, leaving over a hundred dead and two hundred captured.

Bonifacio and his army was no match for the Remington Rolling Block Rifle wielders that swarmed the terrain. The bodies of Kaptipuneros littered the streets, some in gutters and others on the road.

Bonifacio once again evaded capture and retreated with other survivors to the Pasig River. Even though defeated, his actions triggered a series of rebellious uprisings against Spanish rule around the country.

The seeds of a revolution that had been sown deep into the hearts of the Filipinos brought about new leadership under the person of Emilio Aguinaldo in the Cavite region, who led more successful campaigns against the Spanish.

However untrained, the revolutionaries showed real bravery and courage in their fight for freedom. Every last Sunday of the month of August is celebrated every year in the Philippines to mark the Cry of Pugadlawin and the birth of the Philippine Revolution.