The Bozeman Trail served as a gateway to the northern gold mines and forests of Montana allowing wagon-loads of settlers to traverse the heart of the Midwest in relative safety. That safety faltered as the natives whose land the trail blazed through grew increasingly resistant to settler inroads to their home.

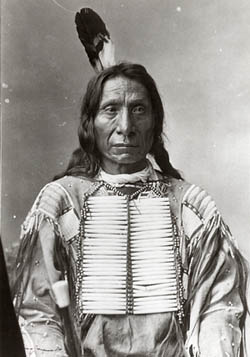

Rallying around a Lakota chief named Red Cloud from 1866-1868, the natives determined to free the Trail’s lands from white encroachments, and his followers went to war against the United States and their native allies.

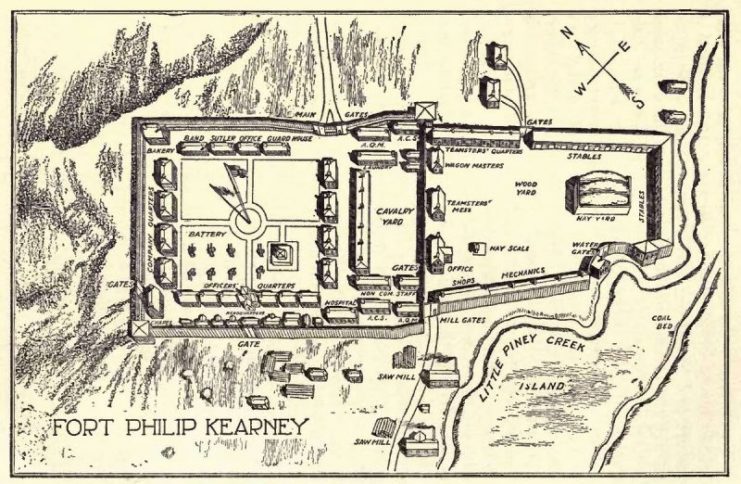

In typical native fashion, Red Cloud’s forces began a campaign of skirmishing and raiding along the Trail, attacking isolated wagons and military outposts. One such example of these tactics was the Wagon Box Fight of August 2, 1867. Taking place outside of Fort Phil Kearney, the battle exemplified such engagements between Indigenous Americans and United States soldiers.

The night before the battle, the local contractors formed a corral to protect their livestock about six miles west of the fort, using the wooden boxes from their wagons to form a primitive enclosure to secure the animals at night.

The corral, situated close by the woods and the contractor’s tents, held a large supply of ammunition so that, in the event of an attack, the workers could rally to the corral for defense. The day before, a skirmish occurred between the Army and the natives, and as a result, the soldiers kept a wary eye on the horizon as day turned to night.

Though the people saw nothing, one soldier present that day noticed the dogs repeatedly running down one of the hills and “barking and snapping furiously.” The dogs’ instincts, coupled with the soldier’s insight, suggested that within the darkness loomed the native forces, waiting. Not long after the soldier’s morning picket duty started, around 7:00 am, the natives announced their attack with a shout.

Finally confirming their suspicions, the soldiers on picket duty readied themselves for battle as seven mounted natives approached from the north in single file, chanting a war song along the way.

Having just been issued new Spencer carbines, and having yet to fire them in battle, the soldiers took care to adjust their sights and ready their weapons for battle. This was a fault with US Army training and supplies throughout the Indian Wars. After taking their shots, the pickets looked toward the camp, and saw “…to the foothills toward the north… more Indians than we had ever seen before.”

With no orders to move, the pickets decided to retreat to the corral utilizing a simple yet effective staggered volley fire as they headed for safety. It did not take long for the natives to bring their own weapons to bear, and the soldiers barely avoided the attack as they made their way to the corral.

The soldiers of the picket line ran, joining with one of the contractors in their retreat while the natives “increased in numbers at such an alarming rate that they seemed to rise out of the ground like a flock of birds.”

Though the natives rushed to cut the soldiers off from the corral, the small group got within firing distance of the defenses, and, thanks to one of the sergeants sallying out to provide covering fire, managed to reach the corral’s limited safety. Finding the escort company’s commander, the soldier, wheezing for breath, explained why he abandoned his picket station without orders –a crime normally punished by firing squad.

The captain lauded the man for his efforts, declaring “You’ll have to fight for your lives today!” Thus rallied, the soldiers and civilians prepared to fend off an unknown horde of natives, their only defense being the government issued wooden boxes in the same style and construction that served so well during the Civil War.

The natives came, and the soldiers opened fire as the attackers circled and galloped around them, firing bullets and arrows at the defenders. Despite increasing casualties the native’s attack continued, and the defenders kept up their fire until finally the natives gathered their dead and withdrew.

They returned not long after, however, utilizing the cover of the tents near the corral to block the soldier’s fire. Risking enemy fire, the defenders sallied from the corral to down the tents and open their field of fire.

The battle continued into the afternoon with water and ammunition running scarce and fire arrows threatening the corral. A massive assault of natives on foot threatened to end the fight in their favor, but the soldiers’ fire slowly whittled down the enemy forces during their approach.

The natives unused to western style fighting and preferring less costly skirmish combat, broke and fled. According to the soldier, Red Cloud himself observed the fight from “on top of a ridge due east of our little improvised fort” throughout the battle.

A large portion of the remaining soldiers opened fire on the observing war leader, but missed, hitting the warriors scattered below him instead. Finally, with the rallying blast of a howitzer from Fort Philip Kearney heralding reinforcements, the natives withdrew for good, having sustained heavy casualties while inflicting far fewer in number than received.

Though exact numbers are problematic and there is doubt that Red Cloud actually observed the battle, such skirmishes exemplified the hit and run tactics of the natives. The results of the Wagon Box Fight typified when those tactics collided with well trained, well armed American soldiers prepared to fend off such attacks.