Red Eagle was one of the most extraordinary figures of resistance to the advancing United States of America. A half-breed trader, he led the Red Stick Creek Indians in a war against the United States in 1813-14. Eventually defeated by Andrew Jackson, he went on to become friends with the seventh president of the USA.

The Making of a War Leader

The Creek region, which mostly lies in modern Alabama, was one of the most integrated areas of American settlement. Natives and whites lived alongside and traded with each other. They often inter-married.

Red Eagle, known to his white neighbours as William Weatherford, was the child of just such a marriage. His mother was a Creek Indian from a leading local family, his father a Scottish American. Together they settled down to set up a trading post. Around 1780, Red Eagle was born.

Red Eagle grew up into a handsome and athletic man. Though not interested in reading and writing, he learnt all the languages useful for trading in the region – that of the Creek natives, English, French, and Spanish. By the time of the War of 1812, he was a trader like his father before him and a leading member of the Creek community.

In 1812, war broke out between the British and the Americans. Encouraged by the British, many Creek warriors joined in the Red Stick rebellion triggered by the chief Tecumseh further north. From 1813-14, these rebels fought to throw the Americans off their land.

Red Eagle was among their leaders.

Red Eagle on the Offensive

From the start, Red Eagle led the Red Sticks to some of their greatest successes. This was a small war, with most battles fought between dozens or at most hundreds of warriors. Only in the largest encounters did the numbers reach a few thousand on each side.

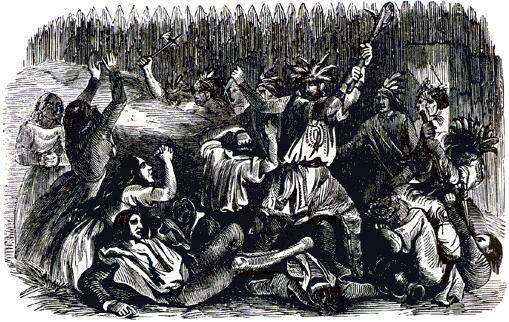

The first great success of the war came at Fort Mims. There, Red Eagle led a band of Red Sticks in a slow, creeping approach to the fort. Though its defences had been reinforced, the defenders were not disciplined or alert. The Creeks were almost at the gate before the sentries spotted them. They then charged, seizing the gateway before the defenders could shut it. Red Stick warriors poured into the American fort.

The fighting that followed was messy and brutal. Soldiers and civilians alike took up arms to defend the fort. But the Creeks had the advantage of surprise and better organisation, so victory was never in doubt.

Towards the end, Red Eagle lost control of his troops. In the heat of battle, they massacred most the inhabitants of Fort Mims. Though the battle was a victory, it galvanised Americans who had doubted the importance of the war.

Andrew Jackson on the Offensive

The man put in charge of driving back the Red Stick Creeks was Andrew Jackson. A lawyer, politician, and commander in the Tennessee militia, Jackson had not yet fought the battle that would make his name – the defence of New Orleans. But he was a capable leader holding a prominent local position, and so was given the task of defeating Red Eagle.

Prior to the arrival of Jackson and his men, the American forces had struggled to gain the upper hand. Now that changed. Despite discontent among his men and disobedience from one of his commanders, Jackson brought his superior weight of numbers and weaponry to bear. The Red Sticks, who had previously raided American settlements in small bands across the region, found themselves facing a far larger threat.

Driven to Defeat

Red Eagle’s attempt to restrain the massacre at Fort Mims had spent much of his political capital among the Red Sticks. They were not professional soldiers, used to obeying every command, and many had scattered to raid the Americans.

To counter the American advance, Red Eagle tried to consolidate his troops at a series of strong points. Each, in turn, was over-run. At the Holy Ground, the presence of prophets casting charms and predicting victory helped to rally a substantial force. But all the charms in the world could not protect them from defeat at Jackson’s hands.

Red Eagle was no coward. He had led the attack on Fort Mims. On another occasion, he escaped the Americans by jumping his horse off a bluff into a river. He was ready to fight, no matter the risk.

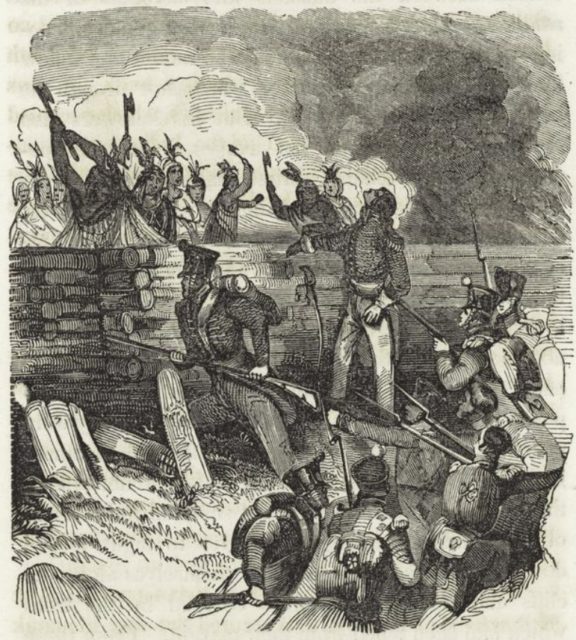

The last stand of the rebels came at Tohopeka or Horseshoe Bend. Here, they found a strong defensive position in the bend of the river and built a wooden palisade to defend.

On the 27th of March, 1814, the Americans attacked. After initial fighting, Jackson ordered a bayonet charge, while General Coffee crossed the river to surround the Red Sticks. Most refused to surrender, and the fighting went on for hours. But with superior numbers of well-equipped and trained soldiers, the Americans could not be beaten. The vast majority of the 1000 Creek warriors present were killed. The rebellion had been defeated

Enemies Become Friends

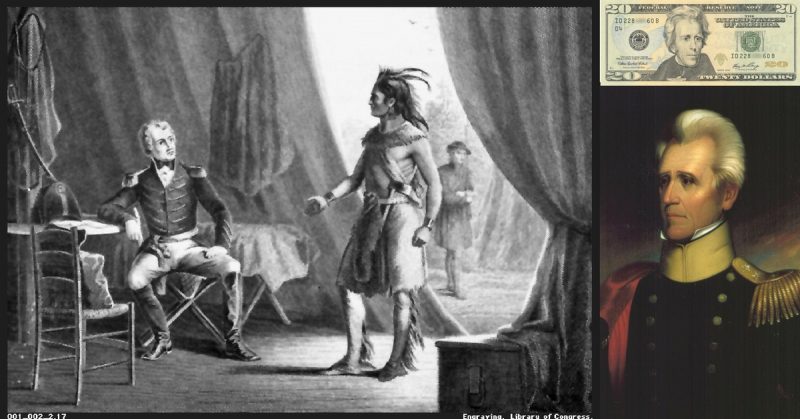

Jackson continued advancing into Creek lands, ensuring that all remaining resistance scattered. The leaders of the rebels sued for peace, but Jackson would only allow this on condition that Red Eagle, who was blamed for the Fort Mims massacre, be handed over.

Red Eagle took matters into his own hands. Risking execution for a crime he had tried to stop, he rode alone into Jackson’s camp and surrendered himself. Confronted by Jackson with the blame for Fort Mims, Red Eagle defended his part in the battle, winning Jackson around.

With the war between them over, these two men became unlikely friends. Once a new peace treaty had been signed, Jackson took Red Eagle with his as a guest to his home in Tennessee, away from the lingering threat of violence in Alabama. Red Eagle stayed with the politician for most a year before returning to become a planter and leader among the Creek people.

Red Eagle died on the 9th of March, 1824, while out hunting.

Source:

George Cary Eggleston (1878), Red Eagle and the Wars with the Creek Indians of Alabama.