War History online proudly presents this Guest Piece from Dean Smith

“At this moment of potential national emergency, Mao chose to smash the Chinese State and the Communist Party. He launched what he hoped would prove a final assault on the stubborn remnants of traditional Chinese culture – from the rubble of which he prophesized, would rise a new, ideologically pure generation better equipped to safeguard the revolutionary cause from its domestic and foreign foe. He propelled China into a decade-long ideological frenzy, vicious fanatical politics, and near civil war known as the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution.” – Henry Kissinger, On China

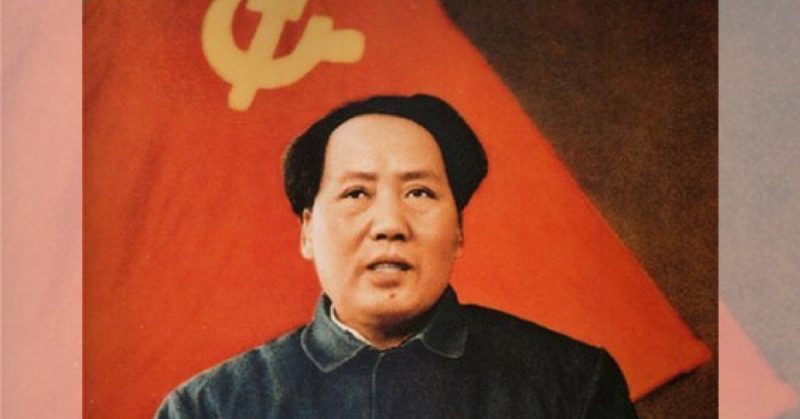

Following the disaster of the Great Leap Forward (1958-1962) and the resulting famine, the position of Chairman Mao and his revolutionary ideology were in jeopardy. Mao was forced to retire as the Head of State but still stayed on as the Chairman of the Communist Party.

Mao had an inherent desire to revive the revolutionary spirit that had prevailed during the communist revolution a generation earlier. This manifested itself in what was to be known as the Cultural Revolution (Dikötter, 2016).

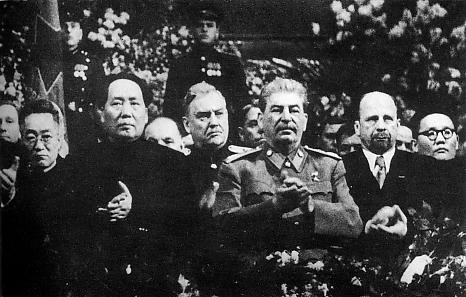

The exact causes of the Cultural Revolution are complex and multi-faceted. Aspects such as Mao’s purge of his enemies within the party, the desire to create an ideologically pure society, the socio-political fallout of the disastrous Great Leap Forward, China’s international position, and the deteriorating relationship between China and the USSR all played major roles (Kraus, 2012).

The events of the Cultural Revolution took place between 1966 and 1976. It was during this period that Mao attempted to reignite the revolutionary spirit of the Chinese population by attempting to vanquish the remnants of the old society.

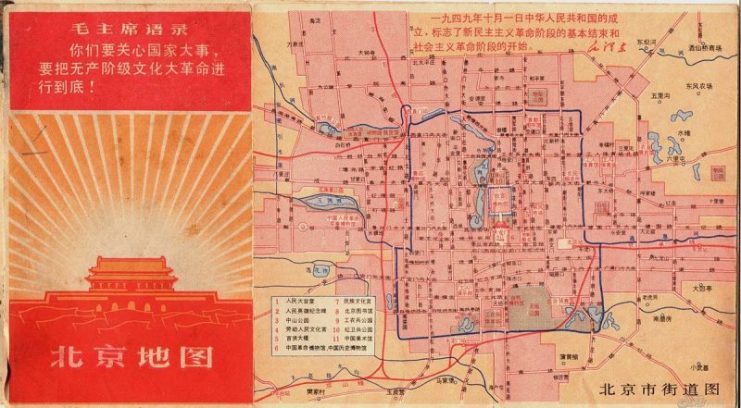

Even though the old bourgeois ruling class had been defeated, it was feared that the values that they represented were still entrenched within society and the psyche of the population. Mao singled out the four “Olds” that had to be vanquished, in order to create a new, ideologically pure, communist society (MacFarquhar, 2008).

These were:

- Old Ideas

- Old Culture

- Old Customs

- Old Habits

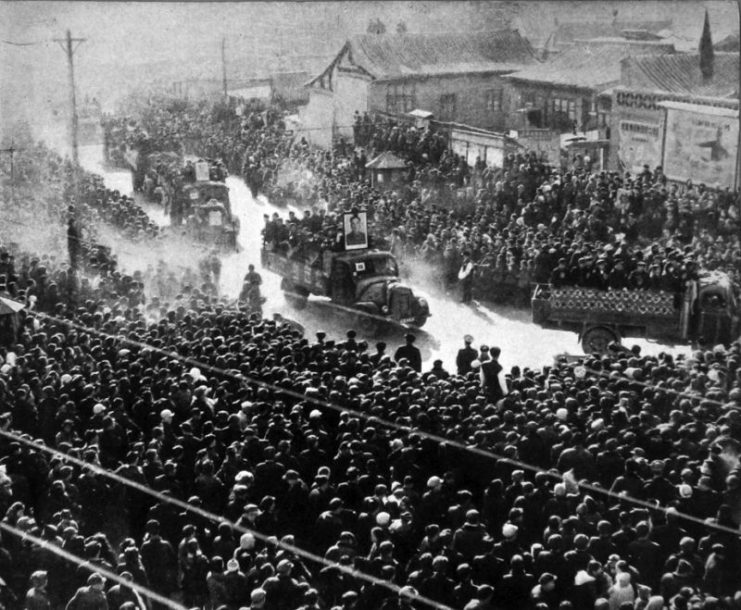

In order to regain control over the party and reassert a revolutionary spirit within the nation, Mao mobilized an arguably underutilized resource – students and young adults. These individuals formed themselves into grassroots revolutionary organizations that referred to themselves as the Red Guard.

This involved a quasi-military uniform of loose-fitting fatigues, a leather belt – which was often used as a weapon to beat opponents with – and a red armband with the insignia of the Red Guard on it, an item that became symbolic of the Cultural Revolution (Esherick, 2008).

Historian Frank Dikotter accurately summarises Mao’s logic in instigating the Red Guard and their activities.

“Mao went straight to the students, seeing in the young his most reliable allies. They were impressionable, easy to manipulate and eager to fight. Most of all, they craved a more active role” (Dikotter, 2016)

In a speech to the Red Guard in Tiananmen Square on August 18th, 1966, Mao whipped the Red Guard up into an ideological frenzy, stating that to rebel was justified and making clear that the “Four Olds” must be purged from Chinese society.

For a while, the Red Guard received a form of tacit support from the state, which turned a blind eye to the violence. Quotes from Mao’s “Little Red Book” were taken as inspiration for revolutionary violence. Furthermore, Mao openly wore the armband of the Red Guard during rallies, giving a symbolic indication of his support for their actions.

By 1967, Mao was forced to reel in the red guards due to the carnage they were unleashing upon the country. In less than a year China had plunged into a state of practical civil war, with the Red Guard carrying out horrendous acts of violence against anyone they perceived to be an enemy of the revolution. Infighting was also common, with different factions of the Guard carrying out attacks on one another for various ideological or personal reasons (Esherick, 2006).

With the Red Guard inflicting heavy tolls on both Mao’s enemies within the party, and anyone they perceived as being counter-revolutionary, the stage was set for Mao’s consolidation of power within the party.

“To Rebel is Justified” – Mao

The Red Guard inflicted systematic humiliation and terror upon anyone they perceived to be an enemy of the revolution. This included individuals who came from the wrong class background, remnants of the petty bourgeois, anyone who was classified as a “capitalist roader”, teachers, members of the party, local government officials, and sometimes even their own parents (Clark, 2008).

The violence inflicted by the Red Guard was initially intended to humiliate individuals who they perceived as embodying the old ways and thus enemies of the revolution. Individuals were often publicly beaten and shamed, whilst being forced to wear placards or “dunce hats” with their alleged crimes written on them.

As the revolution progressed the acts of violence rapidly became more intense, with individuals regularly being beaten to death and others opting to commit suicide rather than die at the hands of the Red Guard attackers.

Estimates of the death toll vary wildly. However, most put the loss of life somewhere between 400,000 and 3 million. This is due in part to the localized environment of many of the acts of violence and because the government actively tried to cover up and censor the reports of violence in later years.

For example, between August and September 1966, roughly 1772 people were murdered in Beijing alone. However, in the Wuhan district, the violence claimed only 32 lives yet resulted in 62 suicides. In certain parts of the country, the average daily death toll was in the hundreds.

Evidence suggests that the violence was heterogeneous, with the levels of violence differing between provinces. The violence carried out by the Red Guard was grassroots and self-propelling, it was not directed and controlled by the state authority.

Many of the individuals who became prominent in the Chinese government in the decades following the death of Mao were at one-point members of the Red Guard.

Furthermore, violence was not limited to personal attacks. Temples, shrines, statues, and symbols of the old cultural traditions were destroyed. This was most apparent in the desecration of the grave of Confucius, who, by the standards of the revolutionaries, embodied the old traditions of China.

It should also be noted that not all of the violence perpetrated during this period was inherently ideological in motivation. Many of the attacks were carried out against individuals who the attacking guard members had personal vendettas against.

It was not uncommon for roving bands of revolutionary Red Guards to single out and extract vengeance upon individuals or groups with whom they had a long-standing personal vendetta. It seems that personal motivations were inherently linked in with the political when it comes to acts of violence in revolutionary China.

According to interviews conducted with ex-members in later life by Frank Dikotter, it can be shown that the Red Guard were active participants in the Cultural Revolution. They chose to commit the acts they did, they were not simply swept up in the political machine of the state or a “culture of cruelty”. They were consciously active and willing participants.

Personal accounts of the cultural revolution

There are countless accounts of the brutality and terror that the Red Guard inflicted on the population.

Some anecdotes from survivors read as such:

“Several hundred villagers were also ordered by authorities to attend and to “struggle” with the “struggle target” or “class enemy” by verbally, and sometimes physically, abusing him or her.

“My father was labeled a ‘history counterrevolutionary’ and was required to have that title pinned to his clothes on a card at all times, in public and at home. The criticizing meetings were organized by a Cultural Revolution Leading Committee, a special governing agency of the Communist Party. During the meetings, my father had to kneel for over three hours while people berated him loudly and violently. People shouted over and over: “Beat down Liu Shibao! Beat down Liu Shibao!” Some people made up false stories about my father, making people hate him. Some people became very riled-up and out of control that they would spit at him and beat him.”

– Yukui Liu, A Memoir of China’s Cultural Revolution

“I remember the Chinese version of Kristallnacht in summer 1966 when waves of Red Guards from different factions repeatedly stormed my bourgeois neighborhood … terrorizing the innocent, ransacking homes and parading victims through the streets for the purpose of public humiliation.”

– Zehou Zhou, Manchester Township, Pa.

After the Red Guard were quelled and sent to the country for the purpose of re-education, the military took an active role in maintaining the state.

The violence associated with the cultural revolution later dissipated and the era finally ended in 1976 with the death of Mao and the arrest of his supporters.