The Empire of Japan cut a bloody swath through the Pacific, committing horrendous atrocities in its desperate bid for resources, prestige, and racial superiority. The Empire’s success would not have been possible without the massive modernization efforts of its military.

Indeed, it was this advancement, undertaken in prelude to the first Sino-Japanese War, that shattered China and paved the way for Japan’s regional supremacy.

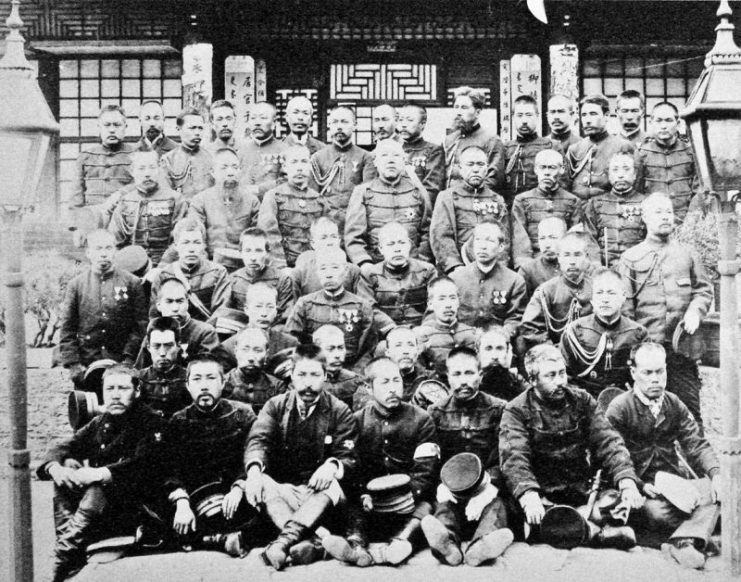

To modernize its military, Japan first needed a modern Army. To facilitate this, in 1873 Japan passed a universal male conscription act, a move that undermined the samurai class from their lofty position in Japanese society. Despite this, their respected position of nobility remained ingrained in the culture despite the earlier dismantling of the feudal structure of Japan during the Meiji Restoration.

Those same samurai families found the conscription decision unpopular as did many rural families, and many young men utilized a variety of methods to avoid military service, some going as far as hiding in secluded Hokkaido in the north. Ironically, the conscription law, advocated by future general Yamagata Aritomo, based on a French model at the time, held several exemptions for service.

Worded as it was, the bulk of military duty fell on the second and younger sons of agrarian families, as firstborn sons were one of the main exemptions of the law.

In 1883 the conscription system was revised to reduce exemptions and incorporate a three-level structure, sorted into three years of active service, four years in the first reserve, and five years in the second reserve, a change based on the increasing prominence of German military advisers.

The ease for the wealthy to reduce their service time, however, remained, and discontent festered due to the unequal nature of the Army. What followed, despite later reform efforts in 1889, was an army of poor farmer’s children led by the leftover elites of a society who looked down on the soldiers with disdain.

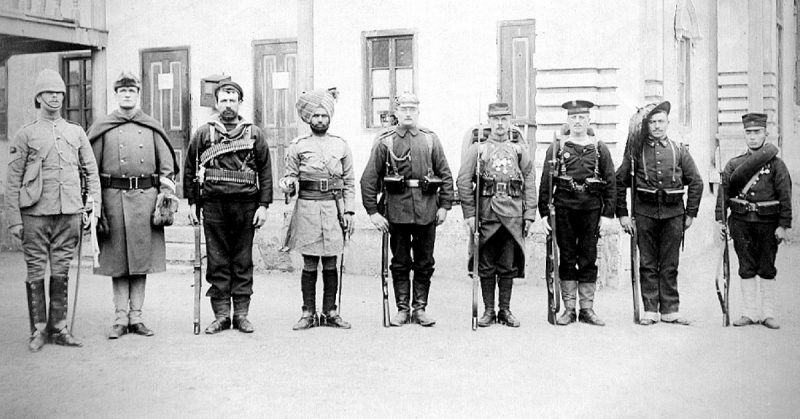

The sort of large-scale armies conscription created required a modernized military framework to muster, document, train, and station those troops and keep tabs on the reservists should they need to answer a call to arms. Japan relied on foreign advisors to aid the transition from a feudal society to a modern one.

During the Meiji Restoration itself, French advisors were some of the most prominent, and that prominence remained as Japan continued to modernize. However, the French defeat in 1871 by the newly formed German Empire brought a new set of advisors and military model to prominence.

German educated Katsura Taro advocated a German-based military system in the wake of Japan’s military failings in Taiwan and Korea under the French model. With the help of German advisors, Japan’s army rebuilt itself from a domestically military model similar to a police force, into a modern divisional army prepared to fight on foreign soil. The changes to the conscription to reflect reservist tiers, noted previously, stand out as one such influence of the German advisors.

While the Army reformed and reorganized, the Navy also modernized. Unfortunately, with Japanese industry not quite up to par, Japan was heavily dependent on the purchase of foreign built ships, or at the very least ships paid for and built in foreign yards.

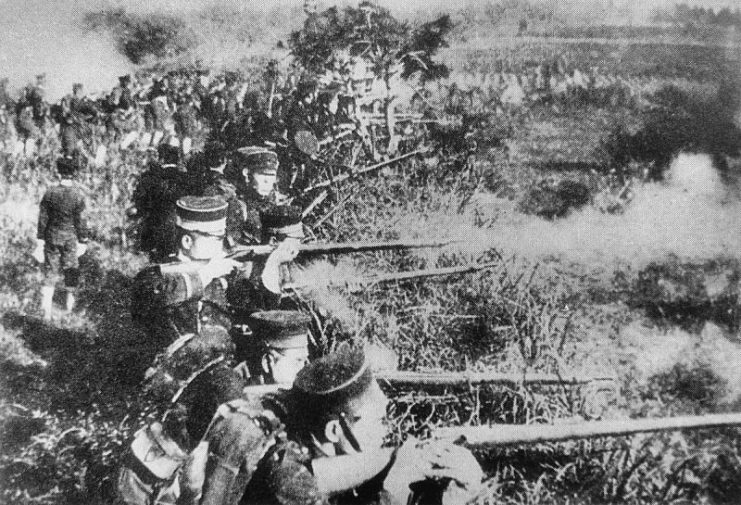

As both branches of the military reformed, they started working together during war drills to form a cohesive military force capable of complex combined arms tactics. How effective such a force would be until tested in the fires of war remained to be seen.

Facing political and military turmoil and the angst of cultural changes ,combined with modernization, many in the Japanese government and military believed only war could unite the people. Japan’s representative in London received word in March of 1894 that

“If we don’t have something to distract the people’s attention, we won’t be able to quiete this ferment….”

For the first time in Japan’s history, public and international opinion mattered; a modern nation, especially an upstart one considered racially inferior by the world powers in Europe, could not start a war without pretext, thin as it might be.

For better or worse, those pretexts would arrive in enough time. Russia, expanding eastward, faced a weakened China in its efforts to build a railroad connecting its massive nation. China, meanwhile, faced an ever weakening hold on its protectorate, Korea.

It would not be long before the newly modernized Japanese military would test itself against the oldest, seemingly most influential and powerful Asian nation: China. Not even a decade later, Japan would once again test itself, this time against a much more formidable foe, the Russians. Both times Japan would win, and both times the Pacific would never be the same.

____________________________________________________________________

BIO:

Christopher Charles Hoitash earned his Master of Arts studying history at Eastern Michigan University. His main fields of historical study are nineteenth century US and European history. He is also fond of studying eras outside of his fields, including Japanese and ancient history.