One of the most intriguing mysteries of the First World War that remains unsolved to this day is what happened to the huge hoard of treasure that Romania entrusted to its Russian allies for safe keeping.

This remarkable national collection of treasure consisted of not only the bulk of Romania’s gold reserves, estimated to be in the region of 120 tons, but also a large collection of valuable paintings, jewels, other works of art, and significant ancient cultural objects.

Even today only a very small amount of the treasure has been returned despite negations which have been going on for almost a century.

Background to events

Romania did not enter the war until 1916 when it decided to give up its neutral status and joined the side of the Allies.It wasn’t long before it found itself under German occupation and made the strategic move of setting up its administrative center in Lasi in Moldavia following the capture of its capital, Bucharest.

As well as shifting their administration to Lasi, the government also decided to move the nation’s treasure, fearing that it could fall into the hands of the occupying forces.

But as the German occupation continued, the Romanian government decided that the safest option would be to get the treasure right out of the country. The best approach would seem to be to entrust it to one of its allies.

The most obvious choices in terms of safekeeping would have been the United States or the United Kingdom where it could be held in the vault of the Bank of England.

However, although there were various countries where the treasure would be safe, the real problem Romania faced was getting it there safely.

Arranging transportation for such cargo would entail a number of serious, possibly insurmountable obstacles. Anything being transported from central Europe at that time faced a real risk of being captured by the occupying German forces, particularly if it had to pass through northern Europe.

Instead, Romania opted to keep its treasure closer to home and send it to Russia. A deal was struck between the two countries and it was agreed that the Kremlin would hold the treasure for Romania for the duration of the war.

Transporting the treasure

In the early hours of December 15, 1916, this valuable freight was loaded onto a train which consisted of 25 carriages. Of these carriages, four were filled with guards while a further 21 carriages were packed with around 120 tons of gold in bars and coins.

That train had an estimated value at today’s prices of over $7 billion, and more treasure was to follow seven months later.As the possibility of a German victory began to look more and more likely, Romania decided to send more wealth to Russia for safekeeping.

This time the cargo consisted of not only the nation’s wealth in the form of the deposits held in the national banks, but it also contained the most valuable antiques and works of art in the country.

Such items included paintings and rare manuscripts dating back to the Middle Ages. There were icons and treasures from the monasteries valued not only for their historical significance but also for the gold and precious metals used in constructing them.

Other things needed to be preserved as much for their cultural significance as their monetary values. These included important archeological finds dating back to ancient Dacia in the 4th century BC as well as the archive collection of the Romanian Academy.

In addition to all that, there were also large quantities of jewelry including that belonging to the Romanian royal family.

Because of the nature of the treasure, it is practically impossible to estimate its value but some suggest that the value of the second load could have been even higher than the first in financial terms alone, even before taking account of any historical and cultural significance.

Attempts to have the treasure returned

At the end of the war, following the Russian Revolution and the Romanian army’s intervention in Bessarabia, the relationship between Romania and Russia deteriorated.

When the new Soviet government took over, all diplomatic ties with Romania were cut and the treasure was confiscated by the Soviet state.Over the years, Romania has made repeated attempts to have the treasure restored but with little success. Although a few small concessions have been made, only a very small proportion of the treasure has been returned.

The first attempt, made in 1922, failed to bring any significant results. A second attempt in 1935 was a little better, and Romania regained some of the material from its National Archives.

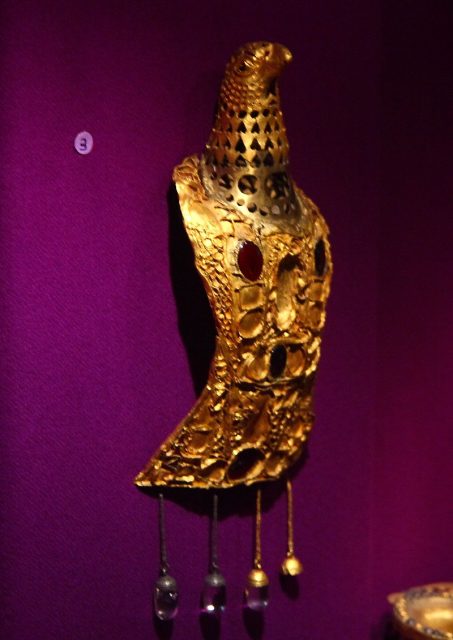

There was another, more successful attempt in 1956 which resulted in the return of some of the paintings and ancient artifacts. The most important of these was the Pietrasele Treasure. This is a collection of solid gold objects, discovered in the Romanian town of Pietrasele in 1837, but dating back to the late 4th century.

Today the actual location of much of the treasure is unknown as it was moved later for a second time. It is thought that during WW2 the treasure was split up and sent from Moscow to different locations considered to be safer.

However, while being transported from Moscow the containers were not sealed as requested and many objects may well have gone missing. The evidence for this was seen when some of the materials were returned. The crates had been broken open, and documents and other items were missing.

More recent Negotiations

Throughout the rest of the 20th and 21st century, Romanian governments have made further unsuccessful attempts to have the rest of the treasure restored.

The situation did not improve following the breakup of the Soviet Union, and successive Russian leaders have been unwilling to negotiate with Romania about the return of the treasure.

Read another story from us: Romania Narrowly Avoided Getting Bombed by the Soviets

Today, discussions on the subject are still active and are taking place within the “Romanian-Russian Committee on the issue of Treasure” who meet periodically to re-open the dialogue and attempt to move forward negotiations as well as conducting research to help identify what is missing.

Nevertheless, at present, the situation remains one of stalemate. The process is held up to some extent by the lack of knowledge of the exact whereabouts of many of the articles and the almost impossible task of estimating the actual value of the missing treasure.