For centuries, samurai held a prestigious position in Japanese society. Emerging in the 12th century, they were the military elite, famously wielding swords when pressed into conflict. Their presence remained strong until the Meiji era, when Japan experienced massive reforms. While some supported the shift, others were against it, with these sentiments resulting in samurai staging the hard-fought Satsuma Rebellion against the Imperial Army.

Background of the Satsuma Rebellion

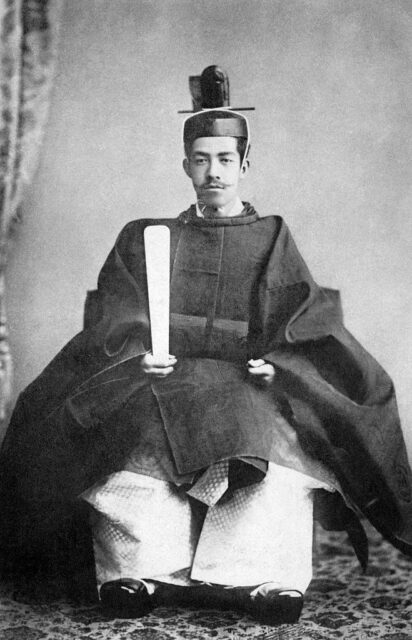

The Satsuma Rebellion of 1877 was a major Japanese conflict, marking the last notable uprising of the samurai against the rapid modernization of Emperor Meiji’s government.

The rebellion was fueled by discontent among the former, who were unhappy with the reforms that the Meiji Restoration had brought about. These included the abolition of the samurai’s privileged status, the dismantling of their stipends and the highly controversial introduction of conscription, which undermined their traditional role as Japan’s warrior class.

On top of this, it aimed to drastically change Japan’s everyday life, impacting everything from clothes and language, to culture.

Early engagements saw the Imperial forces emerge victorious

Leading the rebellion was Saigō Takamori, a former leader in the Imperial Army who’d participated in the Boshin War. He was also a major figure in the Meiji Restoration, known for being one of its “Three Great Nobles,” alongside Ōkubo Toshimichi and Kido Takayoshi

Despite initially supporting modernization, Saigō had become disillusioned with the marginalization of the samurai and the rapid pace at which change was occuring.

The rebellion began in January 1877, when Saigō and his followers, which later amounted to around 20,000, marched from their base in Kagoshima to Kumamoto Castle, hoping to rally support and ignite a larger insurrection. After nearly two months, Saigō and his men lost, but this didn’t diminish their spirits, with them, again, facing the Imperial forces in the Battle of Tabaruzaka.

Taking place from March 3-20, the engagement saw Saigō’s forces outnumbered 15,000 to 90,000. Similar to what took place at Kumamoto Castle, the rebels were no match for the Imperial Army, which was armed with rifles and artillery, weapons that were much more advanced than those wielded by the samurai.

Battle of Shiroyama

The Battle of Shiroyama, fought on September 24, 1877, was the final engagement of the Satsuma Rebellion. For the third and final time, Saigō Takamori’s samurai came up against the Imperial forces, led by Gensui Prince Yamagata Aritomo, a seasoned military strategist and supporter of the Meiji government’s modernization efforts.

Yamagata had extensive experience in both domestic and international military affairs, having studied Western military tactics. He eventually became known as the “father” of Japanese militarism, hinting at the challenge he’d put up against the samurai.

Following their aforementioned defeats, Saigō and his remaining 500 samurai retreated to Shiroyama, overlooking Kagoshima. Yamagata’s forces quickly surrounded the hill and constructed extensive fortifications to prevent the samurai from escaping. A number of warships were also positioned nearby to bombard them.

On the night of September 23, Adm. Count Kawamura Sumiyoshi demanded Saigō’s unconditional surrender, but the samurai leader, adhering to the bushidō code, refused. As night gave way to daylight, the Imperial forces launched an artillery barrage, followed by a full-scale assault.

Despite being heavily outnumbered and outgunned, Saigō and his men fought valiantly, engaging in close-quarters combat with their swords. The samurai leader was mortally wounded during the fight, suffering injuries to his stomach and femoral artery. In keeping with samurai tradition, he committed seppuku, his death marking the end of any real organized resistance.

Now under the leadership of Beppu Shinsuke, the remaining samurai launched one final assault, charging down the hill with their swords drawn. They were quickly overwhelmed and killed.

Impact of the Satsuma Rebellion on Japan’s economy

The Satsuma Rebellion had profound economic implications for Japan. The cost of suppressing the rebellion was immense, with approximately ¥420,000,000 spent, essentially bankrupting the Meiji government. This forced the nation to abandon the gold standard and turn to paper currency. This financial strain led to significant economic reforms, including the reduction of the land tax from three percent to 2.5 percent, in an effort to stabilize the economy.

The rebellion also highlighted the need for a more efficient and modernized military, prompting investments in infrastructure and industry. The Meiji government prioritized the development of a national railway system, improved communication networks and modern manufacturing capabilities.

These investments laid the foundation for Japan’s rapid industrialization and economic growth in the decades that followed.

Decline of the samurai

The Satsuma Rebellion as a whole saw the end of the samurai class, which had dominated Japanese society for centuries.

The Meiji Restoration’s reforms had already begun to erode their status, but the rebellion’s defeat demonstrated the superiority of modern military tactics and technology over traditional samurai warfare. The samurai’s role as the military elite was replaced by a conscripted national army, drawn from all social classes and equipped with modern weaponry.

More from us: Yasuke: The Legendary Black Samurai Who Reforged His Life’s Path

Want War History Online‘s content sent directly to your inbox? Sign up for our newsletter here!

The demise of the samurai marked a significant cultural shift in Japan. While their influence waned, the values of bushidō and the samurai spirit were integrated into the new national identity. The Meiji government kept promoting these ideals to foster a sense of loyalty and discipline within the military and society as a whole.