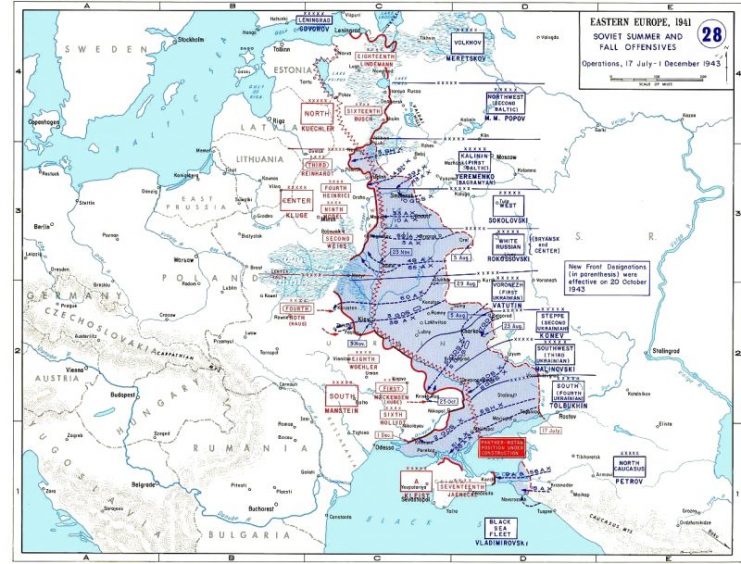

In the Fall of 1943, fierce battles were fought in the Nevelsky district south of Pskov. Troops of the Soviet Third and Fourth Shock Army attempted to clear the occupied territories of German forces and a breakthrough was made.

The daily losses of Russian troops during the offensive were about 2000 soldiers killed or wounded. Over the two months of fighting in the Nevel region, the Soviet forces lost around 43,500 troops. Nevertheless, this did not stop the general offensive and Soviet troops maintained their assault on key positions in the region.

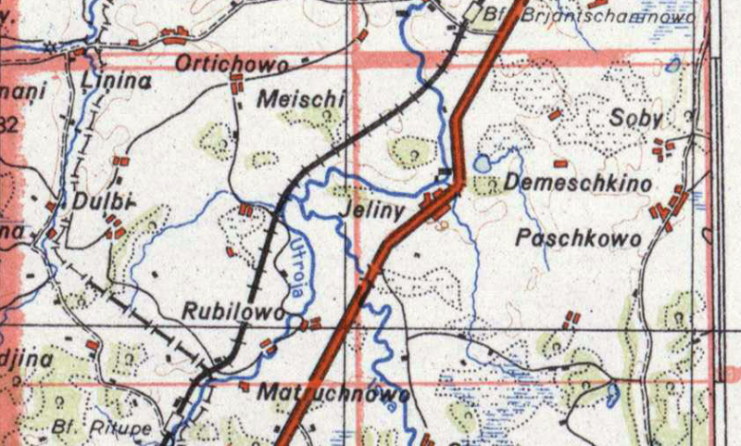

German troops strengthened their positions by bringing in reserve troops. On October 6, 1943, a regiment of one of the reserve divisions arrived north of the city of Nevel in the area of the village of Demeshkovo. Subsequently, the support of the reserve forces in certain sectors stalled the Russian offensive.

In support of the main German forces, the Third Estonian SS Volunteer Brigade was sent to assist in the defense and suppression of partisans in the area. The SS brigades adopted the most radical methods of destroying partisans by firing on civilians, destroyed villages where partisans lived and organizing mass deportations of prisoners of war to Germany. Fearing retribution against the locals, many Soviet soldiers refused to give up the ground they had gained. Amongst these stubborn soldiers was a pair of brave tankers in a T-34.

Even by Russian standards, the roads in the area between Pskov and Nevel were deplorable. The area was filled with swamps and marshes, making supply efforts even more difficult. Consequently, the rare areas of high ground and road intersections were extremely valuable for both the defending German units and the advancing Soviet forces. With the onset of winter, the Soviet advance was slowed considerably.

In December 1943, the village of Demeshkovo and the area around it represented a powerful knot of the German defense referred to only by a hill named 184.2 near a town labeled “Demeshkina.” The junction of the unpaved roads there served the Germans for the transfer of equipment, ammunition, and troops.

This area was strategically important for both German and Soviet armies. Knowing this, the Germans created mortar positions, had three trench lines and camouflaged cannons. In support of the main forces in the area were units of the 502nd German Tank Battalion.

The commanders of the Soviet Third Shock Army decided to attack the area. On December 17, 1943, the battalion of the 118th Tank Brigade received the task: “To seize the village of Demeshkovo and to launch an offensive on the Leningrad-Kiev highway.” However, the plan had problems from the outset.

Captain Dzimiev and his tank battalion, with the support of infantry units, attacked the town and hill. German Pak-38 guns in a fortified bunker, using the superior terrain, were able to target enemy armor with ease.

Machine-gun fire kept the Soviet infantry at a distance and did not allow them to actively support their tanks. In addition, the area was swamped with snow and mud and greatly hampered the movement of tanks for both the Germans and the advancing Russians.

These factors contributed to the damage sustained by four Soviet tanks upon hitting the open area. Soon after, the German fire knocked out two more tanks. During the battle, the commander of the last T-34 tank, Lt. Tkachenko, made an effort to bypass the fortified bunker and attack it from its unprotected side. Unfortunately, during the maneuver, Tkachenko’s tank became stuck in a snow-covered swamp. Nevertheless, from this position, he managed to target and destroy the bunker.

Seeing the immobilized tank, the German infantrymen attempted to attack it and surround the crew. The whole crew refused to leave the tank, believing they could get it unstuck. At the same time, the Soviet infantry arrived and was able to keep the German infantry at a safe distance from the T-34. The persistence of the tank crew inspired the infantry soldiers to maintain fire support. Together they managed to hold out until night fell.

Since there was no connection with his commanders, Tkachenko decided to send one of his crewmen, named Kovlyugin, to report and request help in pulling the T-34 from the swamp.

During the night, the Germans continued to attack the T-34 and were able to land a penetrating hit on the tank. In the blast, one of the crew was killed and Tkachenko was seriously wounded. He needed hospitalization. It was decided to retreat and take with him another wounded crewman. In the tank remained Sergeant Chernyshenko and the mechanic-driver Bezukladnikov.

During the next German attack, Bezukladnikov was wounded and then killed. At that time, only one fighter in the T34 tank remained alone against the enemy’s forces.

The next day, a soldier from another unit, Sergeant Alexei Sokolov, was sent to help Chernyshenko. Sokolov was a veteran of the Finnish War (1939-1940), had been through the Battle of Stalingrad and twice survived the destruction of his tanks. He was also a skilled driver and mechanic. Sokolov again made an attempt to get the tank out of the swamp – but without success. By this time, the tank had sunk deep into the mud.

At this point, the supporting infantry were forced to fall back because of mortar and machine-gun fire. The infantry positions of the Soviet troops were now located at a distance of 875 yards from the tank. The German troops were dug in at a distance of just over 100 yards away and were ready to go on the offensive.

For this reason, the two fighters and one stuck tank became the only good firing position in the area. Fortunately, the bad road conditions and the location of the tank made it nearly impossible for an anti-tank gun or German tank to take up a position to destroy the stranded T-34.

Retreating from the tank would be difficult because the German infantry positions had a clear line of site. Therefore, both soldiers decided to fight it out to the end and not leave the relative safety of the tank.

There were not a lot of foodstuffs: cans with stew, crackers, and a little pork lard. Water was taken from the swamp, there was no other choice. The only advantage they had was a large amount of ammunition and the fact that the swamp had engulfed the tank and covered many of its weak spots.

From the memoirs of Chernyshenko:

“Frankly: these battles in the siege have merged into my memory as one endless battle. I cannot even tell one day from another. Fascists tried to approach us from different angles, in groups and alone, at different times of the day. We had to be alert all the time. We slept in fragments, alternately.

The hunger tormented, the metal burned our hands. Only working at the gun and machine gun created a little warmth, but the hunger was harder. No matter how we stretched the miserable supplies of food, it was enough for only a few days. We were both greatly weakened, especially Sokolov, who received a serious wound … “

Once again under the cover of other infantry including MG-42 machine guns, the Germans attacked the tank crew. Unfortunately for the Germans, the anti-tank equipment could not get into this swampy terrain and their supply of Panzerfausts was exhausted.

Day after day, the Nazis systematically attacked the tank, but their attempts ended in failure – they suffered constant losses. Having lost the hope of seizing the Soviet tank with the crew, the Germans began to direct attacks from large guns and mortars. One shell struck the armor and wounded the soldiers, but they did not stop resisting.

On December 29, the last shell was completed in the tank. There was no ammunition for the turret machine gun. Of the regular weapons, there were several grenades and a sub-machine gun. Having repulsed the last German attack, Chernyshenko, at the request of Sokolov, left one grenade “for himself.”

“Die, do not give up” – in these words was the whole point of the struggle of the two Soviet soldiers.

On December 30, on the thirteenth day, Soviet troops captured the village of Demeshkovo. By this time Sokolov was unconscious. Chernyshenko, realizing that they had survived another night, drew the attention of the allies. Both tankers were in a serious condition and were sent to the hospital.

Text from the award sheet:

«… In this position, they were 13 days, bleeding, hungry, in the cold, and continued to defend their tank. On December 30, 1943, as a result of the arrival of our units, the territory on which the tank was located was liberated, Sokolov and Chernyshenko were taken out of the tank and sent to the medical battalion where Sokolov died on December 31 …»

Viktor Chernyshenko survived but suffered from severe frostbite. Both of his feet were amputated, and other wounds required additional surgery. He spent more than one year in various hospitals. In the end, he had to learn to walk again. Both tankmen, for courageous actions, received the title of Hero of the Soviet Union. Alexei Sokolov is buried in the place of his last heroic battle.

After the war, Viktor Chernyshenko earned his law degree, worked as an assistant prosecutor and later became a people’s judge. Even after experiencing such events, he returned to normal life and lived until 1997.