A long used euphemism in sailing circles, and in some pubs and bars, refers to slurping liquor from a straw directly from the barrel. The practice is called “sucking (or bleeding) the monkey”, and also known as the title of this article suggests, “tapping the admiral”. The liquor in question, the one most likely to have been used to pickle Great Britain’s most esteemed military hero, was brandy – which is sometimes referred to as “Nelson’s Blood”. Many English pubs are named “The Lord Nelson”, for this rather than in his honor.

The story of how these phrases came to be is a story of a great man, his astounding last moments, the sharp thinking of an Irish surgeon, and the creepy shocking rumors of a crew imbibing the spirits of their venerated leader.

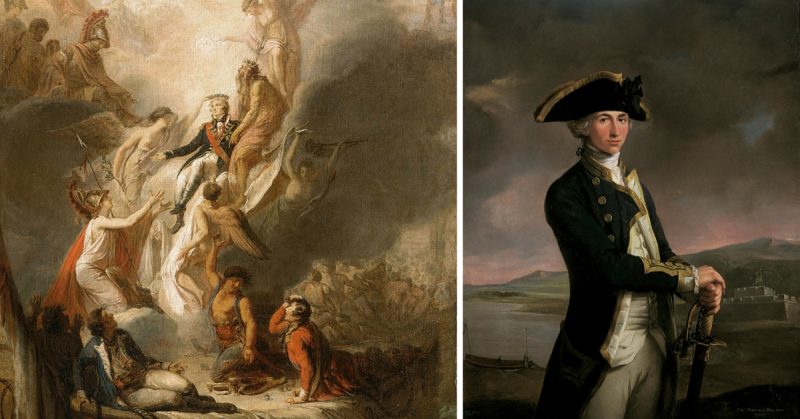

A Heck of a Guy

Admiral Horatio Nelson was an impressive character, even as a boy. Even though he was a frail boy, prone to illness, he swashbuckled in play along the rivers of his hometown, always with an ear for anyone who would tell him seafaring stories.

His uncle, a Royal Navy captain, took the boy on his first voyage at the age of 12. It wasn’t just around about the channel, either – he took him all the way to the Falklands and back. Horatio was a quick study, and by the time he was 20 was in charge of his own ship.

As he rose ever higher through the ranks, it wasn’t by back-scratching or double-crossing. Horatio earned it by merit and integrity. He was a keen strategist that was also talented at in-the-moment tactical brilliance. He also genuinely cared for the morale of his crews and was a popular leader.

His popularity was not due only to his treatment of those under him, it was also because of his inherent nature to not fall down in the face of adversity. He kept up the fight when wounded, whether it be the loss of an eye, the loss of an arm, or in the throes of death itself. It is said that he joked about the remaining part of his arm being his “fin”. He never shied from truth and always demonstrated his valour.

Victory in Death

Nelson met his fate while commanding the Victory through the Battle of Trafalgar. On October 21, 1805, he had 27ships against Spain’s 33, with no thought of possible defeat. When the enemy began its approach, Nelson, as he was wont to do, decided to use an unusual strategy to battle it. Rather than arrange his ships in a straight line, which was the orthodox method, he formed two perpendicular columns. It was a success.

He may have known, however, that though he would win the battle he would lose his life. Before the volley really got going, he went below decks and wrote his will, then checked on things on deck before returning below to write a prayer.

As the battle raged, it was suggested that Nelson take the decorations off his coat. The Victory’s captain, Thomas Hardy, knew that sharpshooters would be looking to fire on the Admiral. Nelson’s response was that he had no time to be changing his coat and that he respected the ‘military orders’ of the coat. He also did not want fear of the enemy to overshadow honor.

Nelson also refused his removal to two other ships and carried on as the lead ship in the battle. In the fight, men upon his ship were dying horrifying deaths – one man split in two by a cannonball. Through all of this, Captain Hardy and Admiral Nelson remained on deck encouraging and directing their men despite the carnage and danger.

Nine hours into it, Captain Hardy turned around to see Nelson down. He had been shot in the spine. As they carried him below, even though he was in great pain and was fully aware of his impending death, the great naval hero stopped the men carrying him so that he could speak to a tiller operator and give him pointers. Working till the last, caring for everyone before himself.

Irish surgeon, William Beatty, who was afforded great respect despite the disregard of the Irish, was told by Nelson that nothing could be done. “I have but a short time to live”, he said. The surgeon administered wine and lemonade and tried to make the admiral’s last moments comfortable.

Nelson held onto life for three hours, during which he continued to give orders between entreaties to send statements of love to his mistress, Lady Emma Hamilton. His last words were, “Thank God I have done my duty . . . God and my country.”

Preservation of Greatness

During the battle, the Victory had sustained a great deal of damage and a subsequent hurricane had taken the mast. Beatty made every effort to preserve the body for the long journey back to London. That trip was going to take almost two months.

It was common knowledge that a corpse could be preserved in rum, but Beatty rightly decided to use a higher proof liquor – brandy. He mixed camphor and myrrh into the cask of brandy and placed the admiral inside. Once during the voyage, the gasses of decomposition caused the top of the cask to pop off, terrifying a nearby sailor.

When they reached shore in Gibraltar, he moved the body to a lead lined coffin and refreshed the same mixture. Word was sent to England about Nelson’s death, aboard a bad pun – the HMS Pickle.

Beatty said of his decision to use brandy, “…a very general but erroneous opinion was found to prevail on the Victory’s arrival in England, that rum preserves the dead body from decay much longer and more perfectly than any other spirit, and ought therefore to have been used: but the fact is quite the reverse, for there are several kinds of spirit much better for that purpose than rum; and as their appropriateness in this respect arises from their degree of strength, on which alone their antiseptic quality depends, brandy is superior. Spirit of wine, however, is certainly by far the best, when it can be procured.”

Some say that when the cask reached shore, it was empty of all but the admiral. Legend has it that there was a small hole drilled in the bottom from which the sailors had sipped on the contents. Other sources say it that it never happened and that the brandy was still in the cask when Beatty opened it at Gibraltar.

Whether the legend is true or not, the euphemisms and nicknames remain.

Beatty’s concoction preserved Admiral Nelson’s body for 80 days. The January 9, 1806 reception and funeral would have rivaled a royal wedding – and in our own day would have cost over a million dollars. Poems of his heroism in life were submitted to papers by the hundreds, and his funeral procession consisted of 32 admirals, 100 plus captains, and 10,000 soldiers.