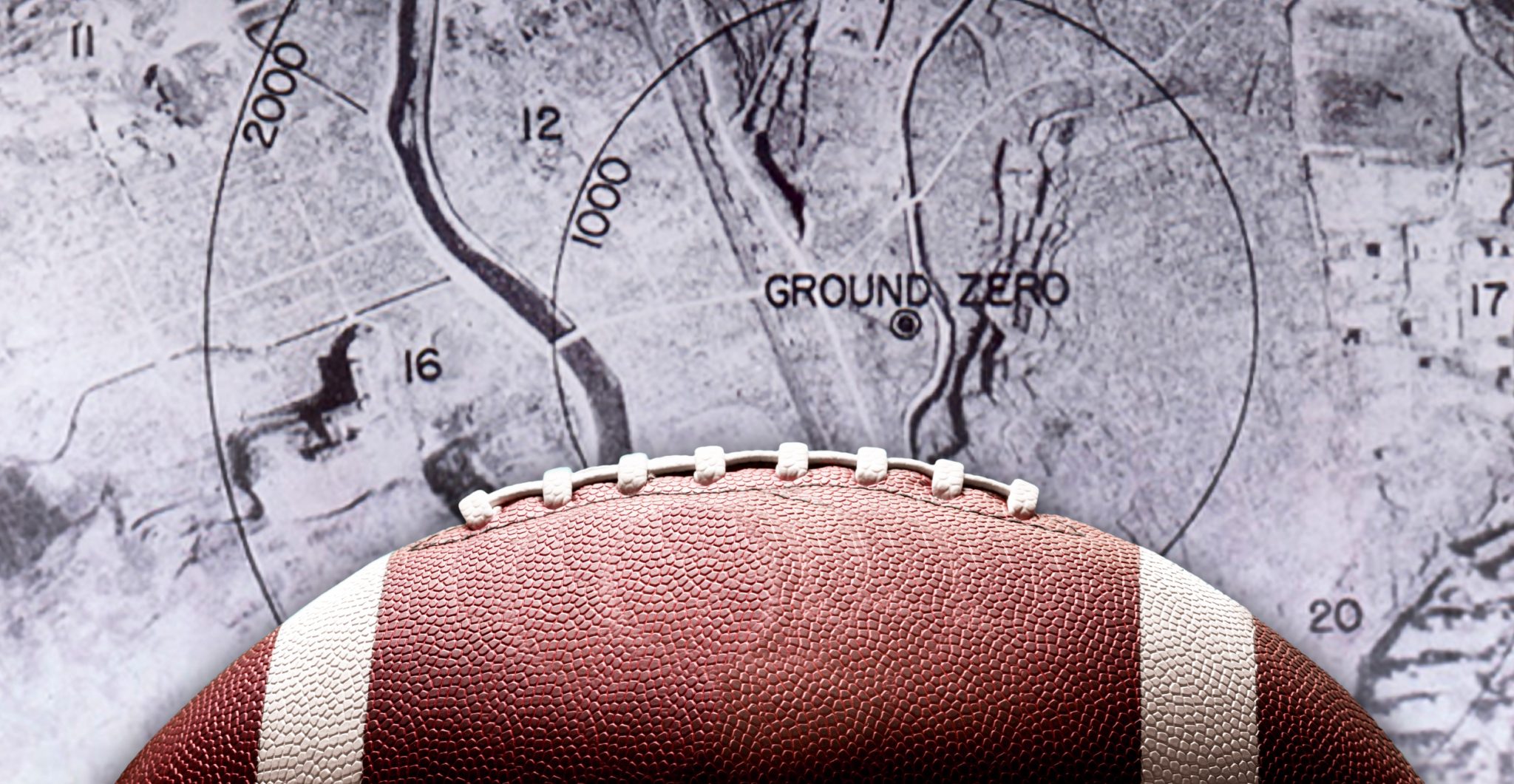

On New Years Day 1946, the U.S. Marine Corps hosted a football game to boost morale for their troops in Japan on occupation duty. The game was held in Nagasaki, not far from “ground zero” where the second atomic bomb had detonated. Think about that for a moment.

People of a certain age will remember all of the times they heard news reports on the unhealthiness of eggs, which then a couple of years later were reversed, then reversed again, etc. It’s almost a running joke.

In “Television’s Golden Years” of the 1950s and early 60s, actors came on the screen to tell the public of the many benefits from…smoking. One of them was Rod Serling, host and chief writer for “The Twilight Zone.” Serling was almost never pictured without a cigarette, smoked 3-4 packs a day, and died from a heart attack at 50.

Years before that, magazine and catalog ads ran advertisements that illustrated the complaints of husbands with “nagging” and “hysterical” wives. The way to solve the problem? Tonics – many of them containing highly addictive substances that are controlled by the government today.

Yes, we sometimes think we know everything there is to know about our health and the way our bodies work, but it always seems that just around the corner there is a new discovery that changes everything. Like nuclear radiation, for example.

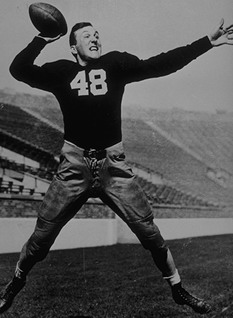

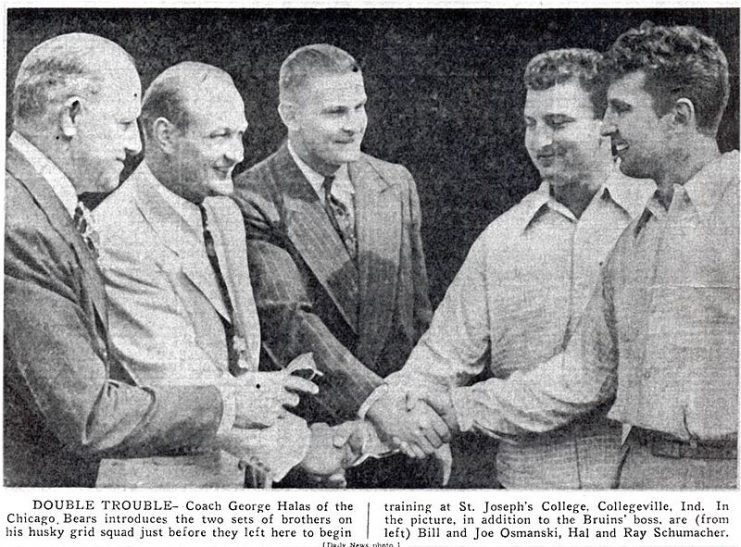

The Second Marine Division, which was stationed in Nagasaki and the surrounding area, had an incredibly high number of college and professional football players in its ranks. One was Angelo Bertelli, Heisman Trophy Winner of 1943. “Bullet Bill” Osmanski, who was a star at Holy Cross and later led the NFL in rushing in 1939 with the Chicago Bears, was also in the Second, as were many others.

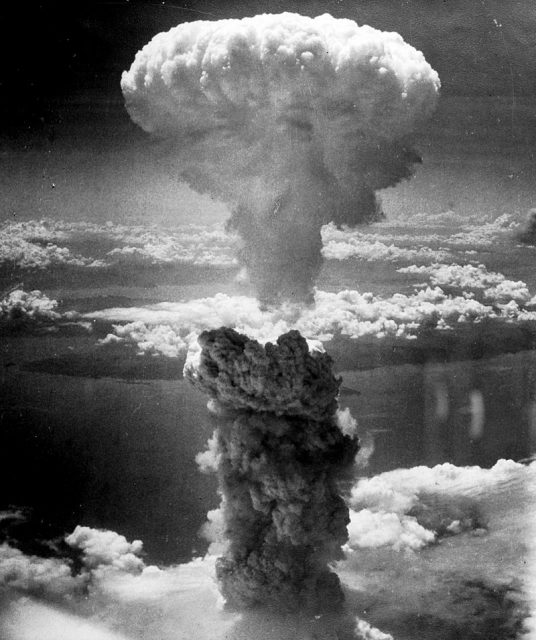

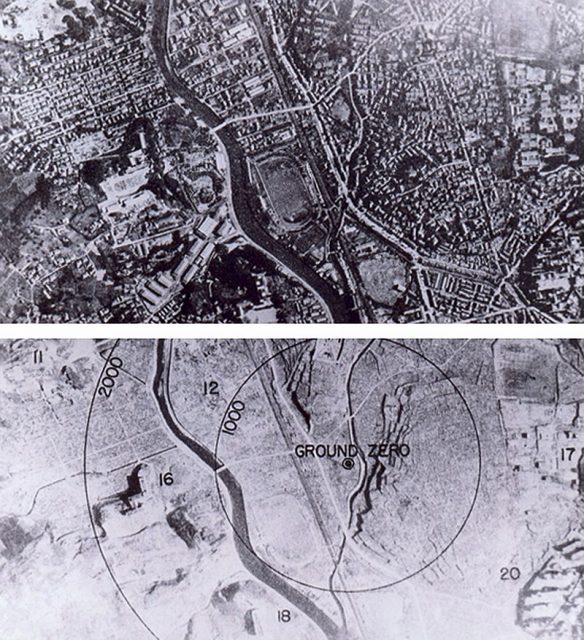

In 2005, Gerald Sanders, thought to be the last surviving member of the Atom Bowl teams, was interviewed by the New York Times. Sanders had arrived with the 2nd six weeks after the August 9, 1945 atomic blast, which initially claimed some 40-50,000 lives with many more to follow.

Everywhere around him there were charred hillsides and mountains of rubble. Sanders was over-awed: “It was just total destruction. A terrible picture.”

Around Christmastime, the 2nd’s commanding officer, Major General LeRoy Hunt, ordered the division’s special services to find a way to lift morale for the holidays – and he wanted a football game.

Of course, as you read this, you are likely asking yourself about the effects of the lingering radiation in Nagasaki. But before we get to that, there is another topic that needs to be addressed. 1945-46 was a very different time from 2003.

In 2003, when many American troops during the initial conquest of Baghdad went about raising American flags on Iraqi statues and government buildings, they were instructed to take them down immediately – the last thing the U.S. government wanted was for the Iraqis to see U.S. forces as occupiers. They wanted to be seen as liberators.

In 1945-46 Japan, the American flag flew everywhere. The Americans wanted the Japanese to know very clearly that they had been conquered and occupied. Many of the men of the 2nd had served in combat units during the war, and had seen incredible violence and brutality close up – and then there was Pearl Harbor. “Political correctness” did not enter into it.

“We thought it was totally appropriate and symbolic of a celebration. It was certainly not to look like there was a joyful glee in what had happened there. It had an emotional effect on us. We were there, yet we had many buddies that didn’t make it through the war,” said Sanders.

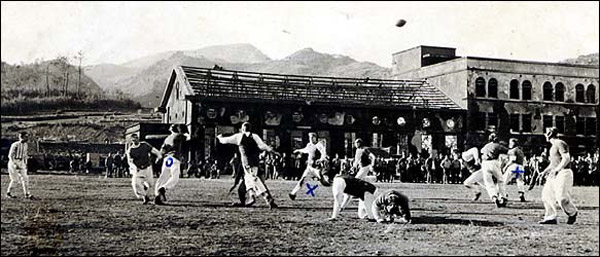

Sanders was tasked with organizing the football game. He asked the Heisman winner, Bertelli, to help him out. They traded with Navy officers for equipment to make goalposts and bleachers for “Atomic Athletic Field No.2”, one of two athletic areas cleared of debris.

Osmanski was the coach of one team and filled it with players from Temple, Northwest, Louisiana, Michigan State and the University of Washington. Bertelli stocked his with players from Duquesne, UCLA, Colorado State, and Texas Tech.

To round out the teams, Marines with high school playing experience joined them. No one is sure who first called it the “Atom Bowl,” but most thought it was General Hunt.

Eleven football players who have gained national recognition on the gridiron are now undergoing Marine Corps training at Parris Island,SC.Backfield Top Left: Angelo Bertelli

Before you begin to think that this was a completely insensitive group of guys, in the nights before the game, Sanders put on a Christmas show for the Marines and invited local Japanese and a Japanese children’s choir, who knew some Christmas songs. Many of the men who were combat veterans did not want the Japanese there, but by the end of the evening, the Japanese kids’ choir and their smiling faces despite all that had gone on around them brought tears to the eyes of the veterans and other Marines.

When it came time to play football, 2,000 Marines showed up to fill the stands, including the general and his staff. Some Japanese looked on from a distance trying to figure out the game. To make matters more confusing for all, the game was to be “two-hand touch” below the waist, to avoid injury from the molten glass shards left over on the turf from the bomb. Also, first downs were fifteen yards.

What many of the men didn’t know was that the fix was in. Bertelli and Osmanski agreed to a tie before the game started, so as not to start any post-game fights. However, at the last moment, Osmanki’s “Isahaya Tigers” beat Bertelli’s team with an extra point at the last second.

Bertelli’s son said, “My dad didn’t lose any sleep over it, but of all the games he played in, he remembered that incident.”

Many of the residents that lived in Nagasaki died from the after-effects of the radiation which lingered in their city. Statistics for the Atom Bowl players specifically are hard to find.

However, another member of the 2nd Marines, Lyman Quigley, was among the first Americans in the city. Starting in the early 1950s, his body began to reject its organs and to grow tumors – one even sprouted from the top of his head.