George Orwell remarked that “the general consensus of opinion is that the only American soldiers with any manners are the Negroes.”

Allied military bases were set up in many places in Britain during the Second World War, and American stoops were stationed at a great number of these bases. Some of those American troops were African Americans, and while they were segregated by law from white troops back home in the United States, no such laws existed in Britain.

Because of this, the arrival of black troops from the United States on British soil, which started in 1942, led to a number of complications. These tensions escalated, and eventually boiled over into a full-scale riot that erupted in 1943 near Lancashire, a riot that was called the Battle of Bamber Bridge.

In this riot, white British residents of the village joined with African American troops to fight against US military police (MP). When the smoke cleared, one person was dead and seven badly injured.

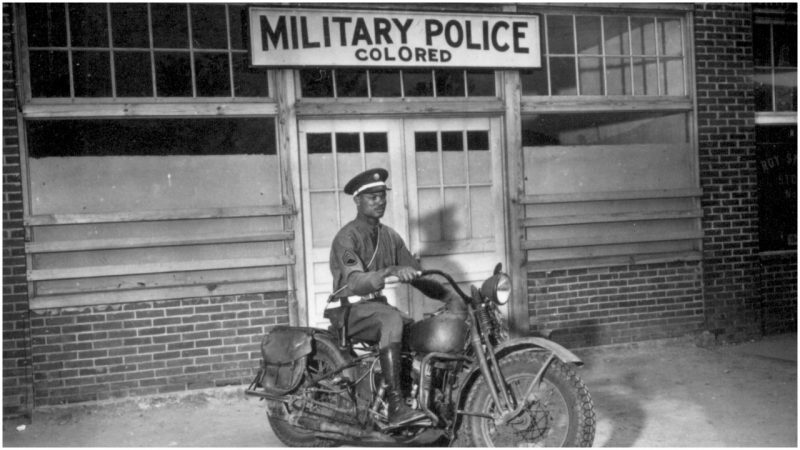

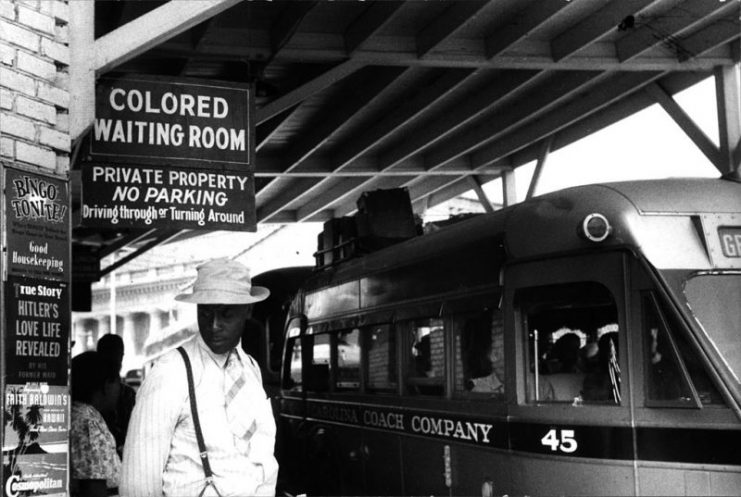

To understand why the riot broke out, it is necessary to look a little further back in history. While African American troops have served in various branches of the United States armed forces since the American Civil War (or, in a few cases, the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812), strict segregation laws in the armed forces – in line with civilian Jim Crow laws – kept them separated from their white counterparts until the 1950s.

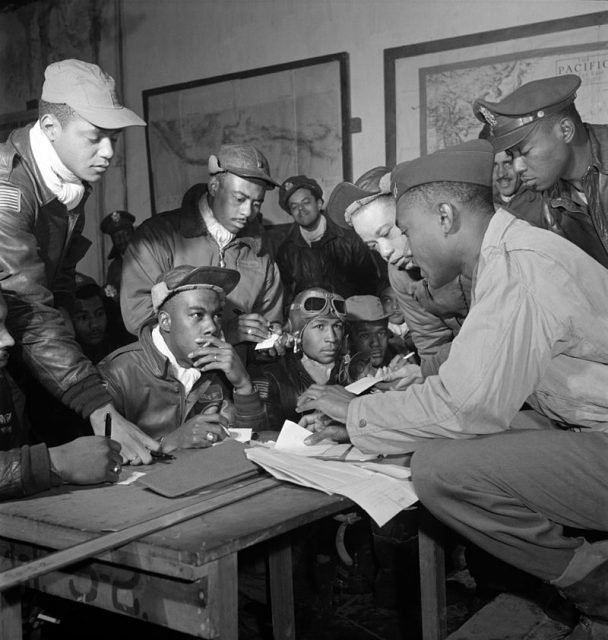

American troops – both black and white – who landed in Britain in 1942 thus brought with them a set of prejudices and deeply-ingrained attitudes about race. While white American troops were generally part of combat units, black troops were usually relegated to non-combat roles, often involving manual labor.

African American troops were used to being segregated from their white counterparts back home – but in Britain no such laws existed, and there was very little in the way of racial prejudice.

Black troops were welcomed with open arms, and were free to fraternize with British men and women in pubs, cinemas, dance halls, on public transport, and in other places with no restrictions. This was completely different from how it was for them in some parts of the US, particularly for those from the South.

Many American politicians and military officials worried that African American troops who were experiencing this newfound complete equality with whites would become “radicalized” and stir up trouble when they had to return to the US. They therefore sought to keep the black servicemen segregated from the local white population.

The British, however, refused to comply with any racist requests from American military police officers. When asked to segregate his pub, for example, one pub owner said that he would gladly do so. When the MP officers returned to check on the pub, the owner had put up a sign saying that only black GIs were welcome.

Most British people welcomed African American servicemen, and often sang their praises, proclaiming them to be more polite and well-mannered than white Americans. Even the famous novelist George Orwell remarked that “the general consensus of opinion is that the only American soldiers with any manners are the Negroes.”

Nonetheless, the American MPs did everything they could to keep African American servicemen segregated from white Britons. It was because of this determination to “rein in” the black troops that a riot broke out in the village of Bamber Bridge on June 24th, 1943.

On that evening, African American servicemen of the 1511 Quartermasters were drinking with off-duty British troops and British civilians at the Ye Olde Hob Inn in Bamber Bridge. Two MPs passing the pub noticed that one of the African American troops was improperly dressed (as he was wearing a field jacket), and attempted to arrest the soldier.

The local Brits, though, backed the African American serviceman, asking why he was being arrested if he hadn’t done anything wrong. Tempers flared, insults were flung around, and soon a fistfight broke out.

While the MPs were beaten back and forced to retreat, they returned with reinforcements. Once again an argument ensued, and this time it boiled over into a more serious battle, involving black servicemen and white Britons against the white MPs, in which a shot was fired and an African American serviceman was hit in the neck.

The shooting of the serviceman temporarily quelled the riot, but when a truckload of MPs arrived at the camp later that night armed with a machine gun, panic rippled through the African American troops, who thought that they were going to be shot.

The panicking troops raided the camp’s gun room, taking around two-thirds of the rifles and arming themselves. A large group of the now-armed servicemen then left the camp, and in the darkness fought running battles with the MPs through the town, with each side firing occasional shots at the other.

One African American serviceman, Private William Crossland, did not survive. When the violence finally subsided at around 4 AM the next morning, seven people had been injured. Due to the darkness, few shots had been fired and most had not hit their targets.

While 32 African American servicemen were later found guilty at a court martial of various charges relating to the riot, their sentences were reduced owing to support for the servicemen from the British public, and the mitigating factors of racism and racial slurs from the MPs.

Most of the servicemen were back on duty within a year, and while the riot had largely been kept out of the American press, it was a precursor of what was to come back home: the Civil Rights movement was gaining momentum, and could not be stopped.

In 1948 racial segregation in the US armed forces was officially abolished, and in 1964 the Civil Rights Act was passed, changing the American social landscape forever.