In October 1942, Adolf Hitler issued the infamous Kommandobefehl (“Commando Order”) which instructed German officers to immediately execute any Commandos or troops carrying out Commando-style raids in German-occupied territory. To Hitler, the British Commandos and other special forces were nothing more than “bandits” carrying out raids in defiance of recognized rules of warfare.

Irony aside, this was a deadly serious matter that was brought about by a series of raids on Hitler’s Fortress Europe and possessions in North Africa. The raids not only damaged key installations, killed Axis troops, and gained both valuable intelligence and practice for the later invasion of Europe, but they also seriously damaged Hitler’s image and that of the Wehrmacht.

These raids began in 1940 and increased in size, frequency, and destruction. One of the more successful Commando-style raids was dubbed “Operation Biting.” This raid, on the French Channel coast at Bruneval, was particularly damaging both to Hitler’s prestige and to the German war effort.

The aim of the raid, carried out by a joint force of men mostly from the British 1st Parachute Brigade and a smaller number from actual Commando units, was to investigate, capture or destroy suspected Nazi radar sites on the Channel coast. By the time of the raid in February 1942, the British were carrying out both larger and more frequent bombing raids over Germany and German-controlled northwestern Europe.

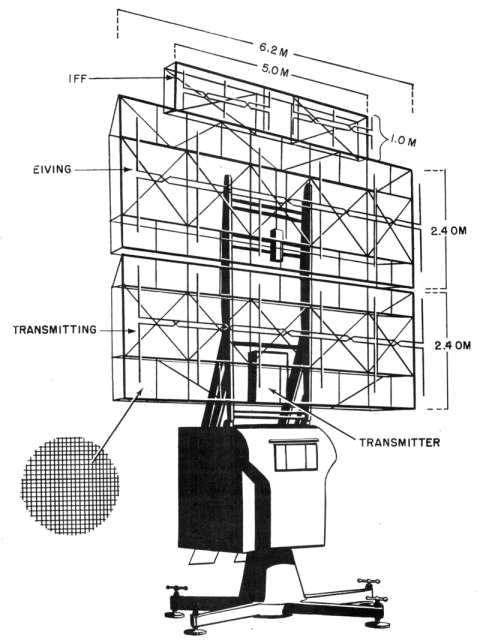

Along with the increase in flights came an increase in casualties, and one of the reasons was because the Germans had developed highly effective radar and placed it on the coastline. This gave both fighters and anti-aircraft units ample time to be on station and prepare.

By investigating, photographing, and maybe even returning to England with one of the German radars, the Royal Air Force (RAF) could develop more successful counter-measures. They might also learn a thing or two to increase the effectiveness of their own radar systems.

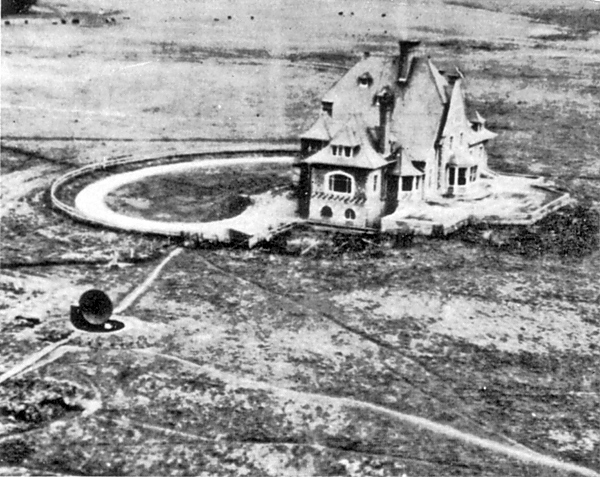

Leading the effort to mount a raid on the German radar installations was Lord Louis Mountbatten, commander of Royal Navy Combined Operations. A reconnaissance photo taken over the chateau of Saint-Jouin-Bruneval appeared to confirm something British intelligence had previously reported: a small but powerful UHF (ultra-high frequency) radar dish that was code-named “Würzburg.”

Bruneval was not far from the British coast and had the topography been right, the site would have been ripe for a raid from the sea. However, Bruneval was shielded from the Channel by high cliffs and, more importantly, German coastal fortifications.

Any amphibious raid would be doomed before it really began, so Mountbatten and his staff decided the best option was to drop on the site from above, utilizing the newly-formed 1st Parachute Brigade, soon to be dubbed “The Red Devils.”

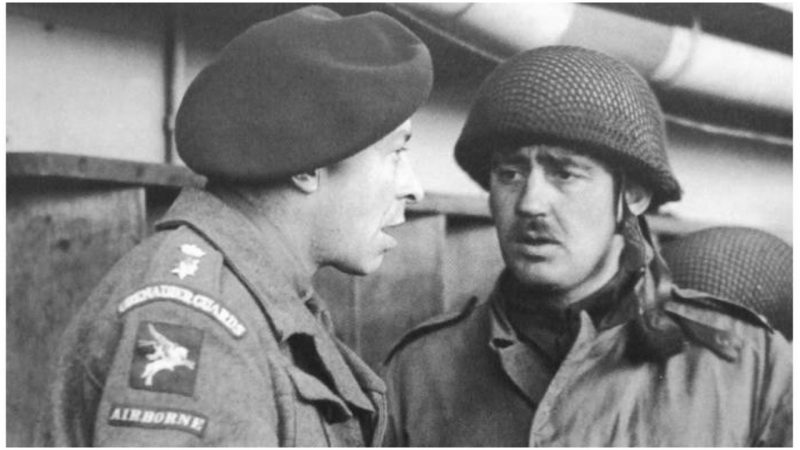

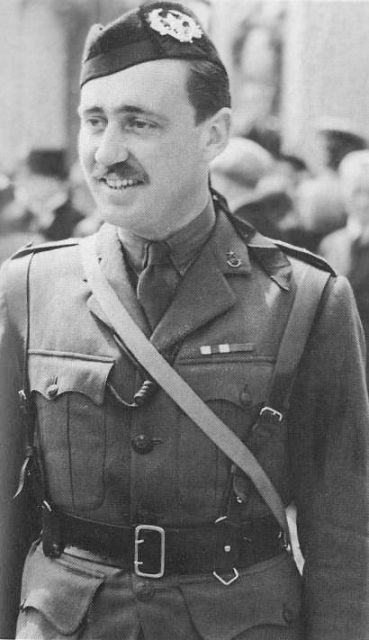

Commanding the troops was Major John “Johnny” Frost, who would later lead them in the desperate fighting at Arnhem, Holland in 1944. The brigade began training in January 1942 and continued almost until the day of the raid.

They were teamed with crews from RAF Bomber Squadron 51, flying Armstrong-Whitley medium bombers. Also joining the Paras would be men from No. 12 Commando who would secure a small beachhead nearby, from which the Paras would be evacuated after the raid. A small force of landing craft and torpedo boats would be used to carry the men back to England and protect the convoy.

The force was scheduled to drop on February 23/24, but bad weather made the raid impossible. Finally, on the 27th the weather cleared and the order was given to launch to raid. As they crossed the French coast, German anti-aircraft fire lit up the sky, and the bombers had to take evasive action. Despite this, the troops landed near their objective – most of them.

The men who were to form the rear-guard, dubbed “Rodney Force” landed more than two miles from their target. In a foreshadowing of a much worse situation that he would face in Holland in 1944, Frost found that his radios did not work, and runners had to be used to communicate in the darkness.

Despite this, Frost and his men proceeded. One section rushed the chateau, but found to their relief that the mansion was empty save for a lone guard who was killed when he fired upon the raiders.

Another section captured the Würzburg radar site, along with a lone German radar operator. RAF Sergeant C. W. Cox, a radar specialist, had accompanied the paratroops. He was tasked with examining and, if possible, dismantling the radar and taking it back to England.

On the beach, the Commandos, dubbed “Nelson Force” attacked German coastal emplacements and engaged in some heavy fighting. Inland, the men of Rodney Force had begun a jog to their assigned positions and were soon engaged in heavy combat with German units flocking towards the coast and the sound of the firing.

While this was going on, Sergeant Cox grew more and more frustrated at not being able to dismantle the German radar. Finally, he simply grabbed a crowbar from his pack and began banging on the equipment. Surprisingly, he came away with key parts that he managed to carry to England.

However, before they could get back to England, the raiders had to fend off some serious German attacks. As they slowly made their way to the beach, Frost and his men came under fire from the chateau, which the Germans had re-occupied. They were also being fired upon from an unseen machine-gun nest.

Frost led his men on an assault on the chateau, routing the Germans within. They then moved to assault the machine-gun nest but found that the men of Rodney Force had come up and taken it out.

When they got to the coast, the Paras’ radios were still not working. With their backs to the Channel, Frost launched flares to signal to the offshore evacuation force. He also noticed the lights of a large German convoy moving down the coast road towards their position. However, before the Germans could arrive, six landing craft appeared and the men were quickly evacuated.

British casualties were two killed, six wounded and six captured. The Germans lost five killed and three missing presumed dead, along with two captured.

As a consequence of the raid, the British discovered German innovations that improved their own radar technology. They also discovered that the recently developed “Window” (the tin foil counter-measures known to Americans as “chaff”) was effective against the German radar.

Read another story from us: Great Story: When British Commandos Turned Pirate – Operation Postmaster

All of the British troops involved gained valuable experience, and some of the lessons learned at Bruneval contributed to the Normandy invasion in 1944. The raid also gave the British public a much-needed morale boost.

Ironically, the German reaction to the raid, fortifying the radar installations with barbed wire and more weapons installations, made them more visible to combat aircraft, and they became a prime target throughout the war.