How could the Crusaders possibly justify working with people of a different religion?

Many Europeans today remember the Mongols as a existential threat to Europe, so many may be surprised to learn that at one point some of the Great Powers of Europe actually pursued alliances with the Mongols. The French in particular were interested in forming an alliance with the Ilkhanate during the later Crusades. This desire was not solely out of desperation, and in fact numerous Christian kings encouraged the alliance.

What Brought France and the Mongols Together?

The French have long understood the usefulness of forcing their opponents into two-front wars. Famous examples include their alliance with the Polish before World War II, their alliance with Russia before World War I, and their alliance with the Scottish against England.

Less famously, in the 8th and 9th centuries they had allied themselves with the Abbasids against the Umayyads. Naturally, as the Crusades in the Holy Land continued to fail in the 1200s, the French sought to pursue this policy once more.

Hopes for aid from the East began as far back as the First Crusade. By the 1100s the legend of Prester John began to gain popularity, especially when Crusading failures left many Christians searching for good news. The legend foretold of a Christian monarch who would come to the Christians aid in their time of need.

He supposedly lived in Central Asia or India. After the Fifth Crusade, rumors spread of a great king, coming from the East, who had shattered Muslim forces in Persia. He was supposedly the son or grandson of Prester John, and he was coming to claim Jerusalem for Christendom!

Although a large military force had conquered Persia, it was not under the control of a great king, but rather a Great Khan—Genghis Khan himself.

Although the Mongols normally saw others as either subjects or enemies, they made an exception for the French. The Ilkhanate, a division of the Mongol Empire after Ghengis Khan’s death, had been frustrated in its efforts to expand by the Mamluks at the Battle of Ain Jalut.

The Mamluks were also the Crusaders’ primary enemy during this time period, so an alliance would naturally be beneficial for both. However, how did two such different groups grow to trust each other? How could the Crusaders possibly justify working with people of a different religion?

Forming the Alliance

The French were not the first Christian group the Mongols worked with, or even encountered on friendly terms. The Mongols had absorbed several Christian states into their Empire, and allowed them religious freedom. Even the Pope himself reached out to the Mongols in the early 1240s.

Although these communications usually broke down quickly, with the Pope demanding conversion and the Khans replying with demands for submission, it established a pattern of diplomatic relations between Christians and the Mongols.

Mongols had captured several Christian kingdoms, most notably Georgia and Armenia. Since these kingdoms surrendered, the Mongols did not demand their conversion, and instead allowed them to become client states.

Soon, some nobility from these subject lands were sending letters to the West announcing that the Mongols were tolerant of Christians, which was mostly true, and that Christians should be willing to enter into an alliance with them. Between these letters and echos of the legend of Prester John, Christians became more open minded towards an alliance with the East.

When King Louis IX of France landed in the Holy Land for the Seventh Crusade, he was met by Mongol envoys. Surprisingly, perhaps due to recent Mongol military failures, they were polite and did not ask for submission. The Mongols proposed that the French attack Egypt while one of Great Khan Güyük’s commanders attacked Baghdad. An agreement seemed to be in place.

Military Failures

The Ilkhanate was comprised of modern Iran/Persia, much of the Caucasus, about half of Iraq, parts of Anatolia, Northern Syria, and parts of several Central Asian countries. As such, it was theoretically in an ideal position to attack all along the Mamluks’ Eastern front.

Unfortunately for the alliance, Güyük died before the French emissary could reach him to finalize an agreement. His widow reverted to the old calls for total Christian submission.

However, this ultimately mattered very little, as the French invasion was such a catastrophic failure that the Mongols would not have been able to do much. French forces were annihilated during the the Battle of Fariskur, the only major battle of the Crusade.

During the battle the Grand Master of the Templars was killed and King Louis was taken prisoner.

King Louis would try again in the 8th Crusade, this time with a firm alliance from the Mongols. Shortly after the Battle of Ain Jalut, Abaqa Khan had sent emissaries to offer Louis military support as soon as Louis landed in Palestine. However, King Louis decided to land in Tunisia instead.

Since Louis was now so far from the Ilkhanate, there was little the Mongols could do. The 8th Crusade never got off the ground as King Louis, his son, and many of his men died of disease. Most of the Crusaders then went home, although an English fleet arrived just as they were leaving.

One more Try—The English

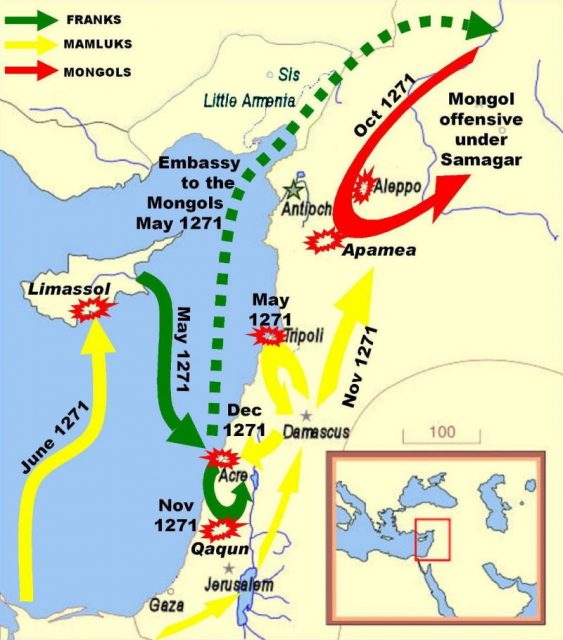

The English decided to carry on to the Holy Land, and landed in Acre. They contacted Abaqa Khan, to continue the “Franco”-Mongol alliance (to the Mongols, all Western Europeans were “the Franks”). Abaqa was happy with this, and asked what date they would launch a coordinated attack.

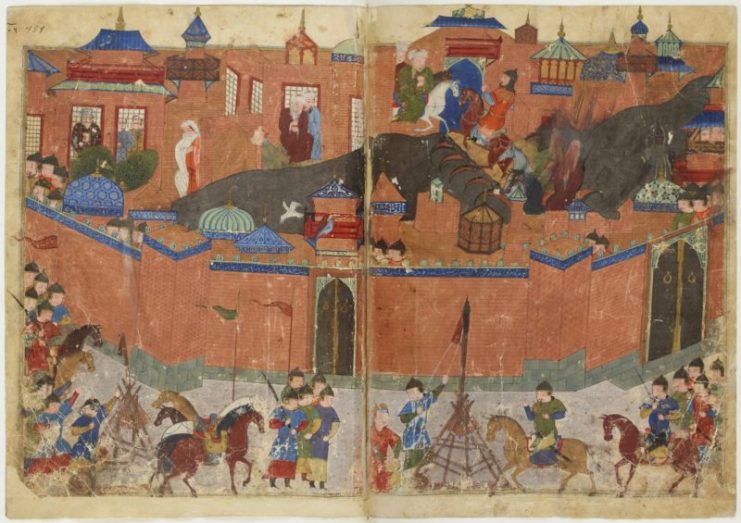

The Ilkhanate launched its attack at the end of October 1271, to great effect. Due to civil wars, Abaqa could only send about 10,000 men, but he accomplished his goals. Muslim populations began to flee his raids, and he defeated some Mamluk forces and took Aleppo.

However, Abaqa decided his forces could not stand in the face of an organized counter-attack launched in November. By mid-November, they had returned to the Ilkhanate.

The English, for their part, also had some success under the leadership of Prince Edward (later King Edward “Longshanks”). They took a few cities and a Mamluk fleet, but ultimately realized they did not have the forces to retake Jerusalem and hold it. Both sides agreed to a 10 year, 10 month, and 10 day treaty. This was the last major Crusade to the Holy Land.

Later Efforts at an Alliance and Legacy

The French and the Ilkhanate kept in contact into the 1300s, but little came of this. The Crusader state of Jerusalem was taken in 1291, this time permanently. The Ilkhanate fell in the 1330s, and the Black Death ended most communication between French and the East.

Read another story from us: Six Years & a Pile of Bones- The Mongols Take a Chinese City

Today, the Franco-Mongolian alliance is often regarded as mere trivia. However, the alliance challenges popular assumptions about both the Crusaders and the Mongols. Few people know that the Crusaders worked with Pagans, rather than just viewing them as a threat to European civilization.

Although the alliances never really accomplished their goals, the subject has become a favorite topic among alternative history speculators. How different would the world look now if a hybrid Franco-Mongol (or Anglo-Mongol) Crusade had been successful?