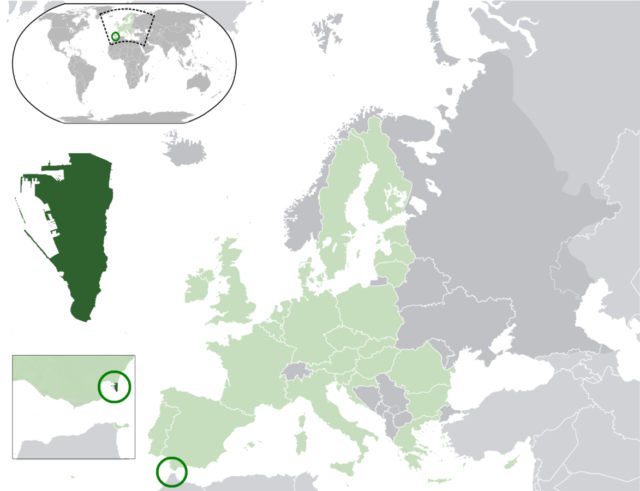

Gibraltar is a small place, but it is full of history. Its total area is only 2.6 square miles, and this tiny landscape is dominated by one famous feature: the great Rock of Gibraltar. Gibraltar is largely self-governing British Overseas Territory and has been an important British outpost since 1704 when it was captured by a combined British and Dutch force. To this day, it remains an important base for British ships and aircraft.

Throughout the centuries of British rule, Gibraltar, located at the southern tip of Spain, has been coveted and claimed by Spain. During the American War of Independence Spain and France formed an alliance and, taking advantage of that conflict, launched a siege on little Gibraltar late in 1779.

At the outset, Gibraltar had a little over 5,000 troops, including some from Hanover and some from Corsica. Britain had expected a siege and had stocked the stores with food and ammunition. Over 13,000 Spanish and French troops led the siege on land and sea.

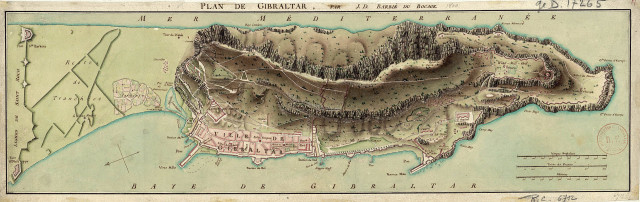

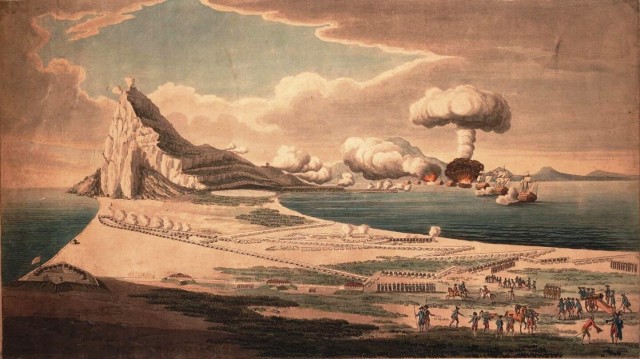

The land army began building extensive fortifications on the narrow strip of land connecting Gibraltar to Spain. Within Gibraltar, general George Eliott organized sharpshooters.

During the siege, cannon fire and sniper bullets flew freely on either side of the narrow land front. As the winter came, the garrison began to run low on food. Scurvy was very common and rations were so low they barely fed the soldiers, but the men’s spirits remained high. They had repulsed several small testing assaults and had great faith that they would receive supplies by sea.

The garrison was correct in their assumption and supplies reached Gibraltar in the spring of 1780. Admiral Rodney had fought two small engagements which he won easily, so he managed to arrive with captured Spanish supply and merchant ships. The defenders recieved a large store of supplies including fresh produce to ward off Scurvy, plus an additional 1,000 soldiers.

These supplies had to last throughout 1780, and as the siege settled in assaults and bombardments became an almost daily occurrence. The British could use the high vantage points from the Rock of Gibraltar to be well appraised of any movements or concentrations of troops. This made it easy to repel attacks and gave a rough idea of where to concentrate firepower. By the end of the year, however, starvation and disease were again a problem. This time, the spirits of the British did not remain high, and some men deserted. According to the diary of a soldier who was present, a few others committed suicide.

In the spring of 1781, a second relief and resupply force arrived at Gibraltar harbor. The Spanish attempted to intercept the force. When they failed to do this, they attempted to bombard the docks while the supplies were unloaded, but again without much success. When the ships left, they took many of the civilian population with them. This gave the garrison fewer mouths to feed and allowed them to operate more freely.

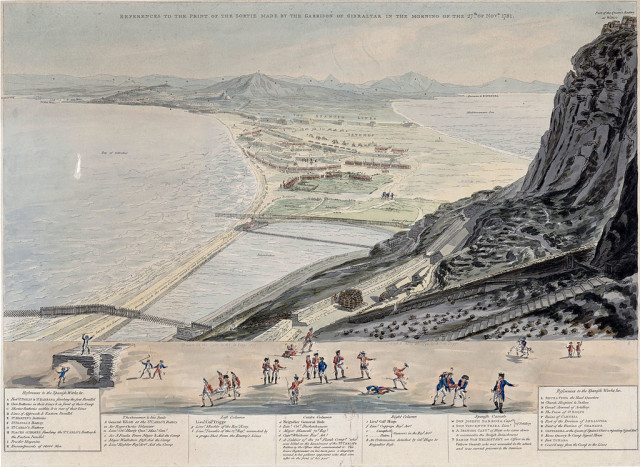

By November, just as hunger began to start again, the garrison received word from some Spanish or French deserters that a massive assault was planned. General Eliott decided that a nighttime sortie to attack the Spanish and French on the eve of their assault would be the perfect move.

On November 27th, several thousand British troops silently organized themselves into three groups in the dead of night. At around two A.M. they marched quietly out and into the besiegers’ lines. Many Spanish troops were killed on the spot as they were so surprised by the attack. The British pushed hard and fast through the front siege lines, destroying provisions and defensive structures while hammering thin nails into the firing holes of the artillery pieces.

This technique was called “spiking the cannon”. Once fitted, the nail was impossible to remove without precise equipment, and even then the chances were high that the piece would be ruined. Dozens of artillery pieces were spiked and thousands of besiegers killed before the British wisely retreated to avoid an organized counterattack. Less than ten British were killed during the sortie.

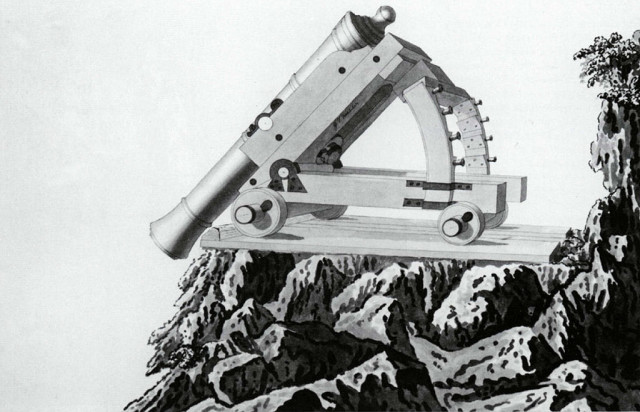

This sortie postponed the great assault for several months. During the next few months, the British began building an extensive tunnel network through the Rock of Gibraltar. This allowed them to build fortified cannon housings into otherwise inaccessible cliffs that occupied most of the Rock’s northern face. Additionally, a new type of cannon mount was invented that allowed a cannon to fire at a downward angle. This made it possible to put more cannons along the heights of Gibraltar knowing that they could strike out far, but also be angled downward to fire on approaching attackers.

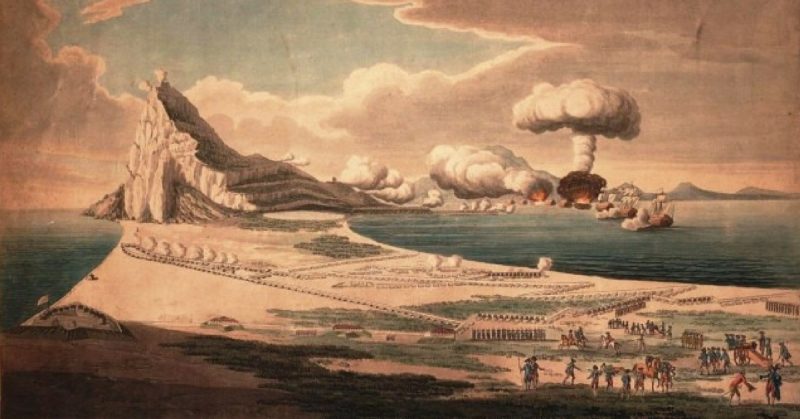

In September of 1782, the great Spanish and French assault began. This massive organized assault was intended to be the last push to finally take Gibraltar. More and more infantry, ships and marines had been dedicated to the siege and the original besieging force of 13,000 had now grown to over 60,000 men on land and sea.

The besiegers had built ten barge-type ships to bombard Gibraltar from the bay along with their many other ships. This was intended to weaken the garrison enough for the land forces to successfully invade. Tens of thousands of Spanish civilian spectators gathered on the hills around the bay to witness the attack.

The grand assault was an utter disaster. The British had recognized the threat of the gun barges and prepared heated shot to fire at them. This was cannon shot heated in a furnace and then fired at ships to set them ablaze. Three of the barges were destroyed outright with at least one exploding as the fire reached the powder magazines.

Throughout the barrages, the other seven barges were so damaged that they had to be scuttled at the end of the engagement. Though the British suffered through the heavy bombardment, they inflicted far greater damage, causing close to 1,000 casualties and halting the rest of the planned assault.

The British garrison was small and could not hope to break the siege on their own, but their spirits were high. They had gone on an outstandingly successful sortie and then withstood a massive assault attempt. The morale of the besiegers was crushed, especially after the third resupply force arrived in September, meeting no resistance due to a fleet-scattering storm the day before. This latest resupply was the largest yet and shortly after the garrison captured a damaged Spanish ship-of-the-line after it drifted too close to Gibraltar.

The situation was turning in favor of the British, and with the end of the American War, they could provide more support to Gibraltar. The Spanish had taken some possessions in the West Indies and they were allowed to keep these, in return for Britain keeping Gibraltar.

The siege was one of the longest in British history. It was fortunate for Britain that the garrison endured, as Gibraltar would go on to play a major role in several wars.

By William McLaughlin for War History Online