After the Battle of Jutland in May 1916, Gillies had to deal with a huge influx of patients who had suffered horrific facial wounds.

War has, since its inception in the mists of prehistory, been responsible for countless horrific injuries and devastating wounds, inflicted on millions of human bodies.

In the age before germ theory and modern surgical practices, comparatively few soldiers would survive particularly devastating wounds. However, with the medical advances of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, more soldiers were able to survive what would formerly have been life-ending battle injuries.

A corresponding problem, though, was that the armaments used in warfare during this period were becoming exponentially more destructive. The widespread use of weapons such as machine guns and high-powered long-range artillery guns meant that the number of serious wounds – and in trench warfare, facial wounds especially – exploded in number.

While horrific wounds have been part of war and battles from time immemorial, explosive shells in particular combined with the positioning of men in trenches in WWI meant that absolutely devastating wounds – such as having one’s entire face torn off by shrapnel – became far more common than in previous conflicts.

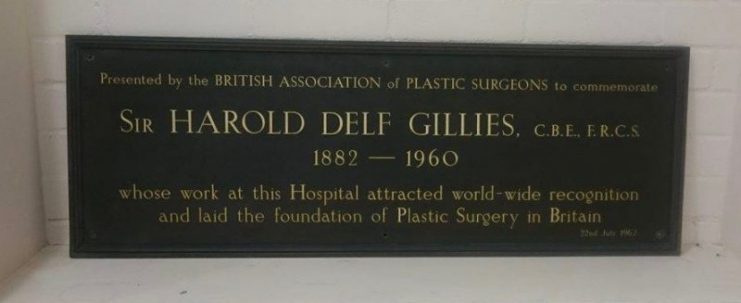

One man, Dr Harold Gillies, who was part of the Royal Army Medical Corps, was so moved by the devastating injuries he saw that he pioneered a new technique to repair the terrible damage: plastic surgery.

Gillies was a New Zealander who had studied medicine and qualified as a surgeon at Cambridge University. He volunteered to join the Royal Army Medical Corps when the First World War broke out. The extent of the injuries he soon began to see got him thinking about new methods to repair the heinous damage to the soldiers’ faces and bodies.

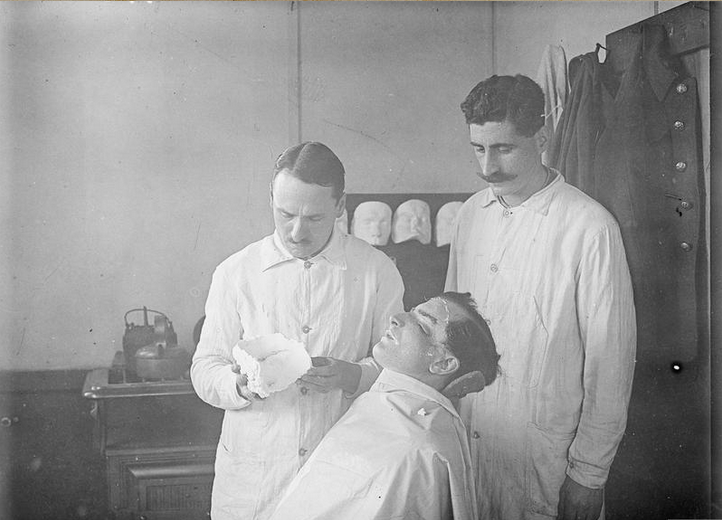

Gillies was initially posted to the 83rd Dublin General Hospital at Wimereux in France. There he acted as supervisor to an unqualified but inventive dentist named Charles Valadier. Valadier was experimenting with basic skin and bone grafts in his attempts to repair the shattered jaws of soldiers who had taken bullets or shrapnel to their faces.

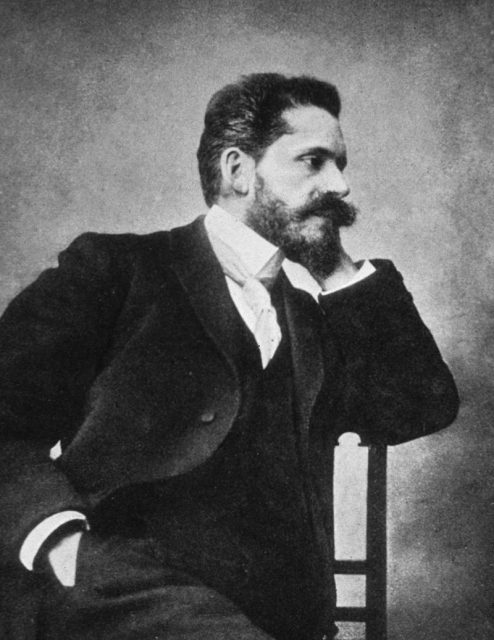

Gillies was inspired by Valadier’s ideas, and after his service at Dublin General, he traveled to Paris on leave to observe the work of another pioneering surgeon, Hippolyte Morestin, who like Valadier was also focusing on maxillofacial surgery.

After seeing Morestin in action, Gillies was convinced that he could take what these two had been doing and apply it on a much larger scale, potentially repairing men’s entire faces rather than just their jaws.

He requested that a facility dedicated solely to facial injuries be established. While his ideas about how he was going to go about repairing soldiers’ torn-off faces were initially met with some skepticism, he was nonetheless given the go-ahead, and a specialist facial repair unit was established at Cambridge Military Hospital in 1915.

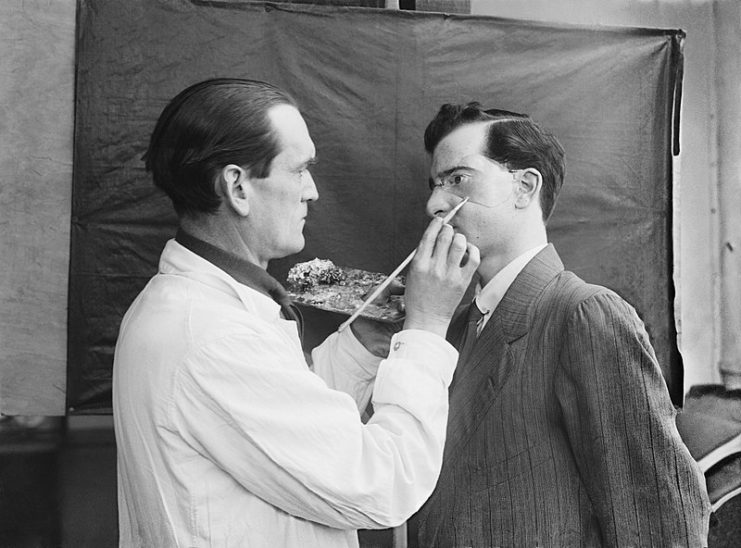

Gillies brought in a number of specialists to collaborate with him, including radiologists for X-rays, dentists, ENT specialists and anesthetists. Also, Gillies enlisted the aid of non-medical specialists to help with the reconstruction of faces: artists, plaster-casters, and photographers.

After the Battle of Jutland in May 1916, Gillies had to deal with a huge influx of patients who had suffered horrific facial wounds. One of his first astounding successes came from one of the casualties of this battle.

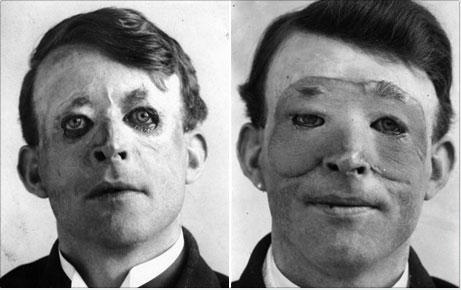

A soldier named William Vicarage had had almost his entire jaw blown off during the battle, but Gillies was determined to fix what seemed to be irreparable damage. Using an innovative new technique he called the “tube pedicle” he took skin grafts from Vicarage’s shoulders and, over time, built it up around his jaw area, eventually fashioning a new jaw.

Of course, not every surgery Gillies performed was a success, and he had to deal with his fair share of failures.

It must be remembered that he was performing his work in a time before antibiotics, and if infection got into the surgical wounds, it would often prove fatal. Nevertheless, Gillies persevered with his pioneering techniques and did, ultimately, see more successes than failure.

After the Battle of the Somme, Gillies’ unit was overwhelmed by the thousands of casualties pouring in from the front. It was obvious that they didn’t have the means to cope with these thousands of new patients at the current unit, so a new hospital dedicated to facial injuries – the Queen’s Hospital at Sidcup in Kent – was established.

Here Gillies and his team performed countless life-changing surgeries on wounded soldiers’ faces, reconstructing jaws, noses, eyelids, and, in some cases, entire faces.

Of course, the repairs made to these horrifically damaged faces were often not perfect – after all, the damage was substantial, and there was only so much a surgeon could do. Some of the men, even after their faces had been reconstructed, still wore masks or refused to go out in public.

Gillies and his team removed mirrors from their units to prevent badly disfigured men from seeing their own reflections, especially during the repair process, which could last months or even years.

He also recognized that the men would need psychological support to deal with the ongoing trauma of living with a permanently disfigured face or lifelong disability, and he introduced training programs to give his patients new skills and prepare them to re-enter society as smoothly as possible.

Read another story from us: Angels’ Glow at The Battle Of Shiloh

Gillies’ work during the First World War earned him the reputation of being the Father of Plastic Surgery, and the techniques he developed in his units ended up being widely applied outside of warfare.

After the war Gillies continued his work with plastic surgery, and ended up performing one of the world’s first sex reassignment surgeries in 1946. Gillies passed away in September 1960 at the age of 78, and will forever be remembered for the contributions he made to the advancement of reconstructive surgery.