In 1814, several European armies invaded France to put an end to Napoleon – the very year that the British attacked the American capital, Washington, DC. This was done in retaliation for US attacks on Canada, which was then British territory. As the city burned, however, the heavens seemed to side with the Americans – an event known as the “Storm that Saved Washington.” But did it really?

It all began with the War of 1812. Though America became independent in 1776, it was still at the mercy of Britain’s powerful navy. America insisted on remaining neutral during the Napoleonic wars and continued to trade with both sides, which infuriated the British.

The British also kidnapped American sailors for their navy (known as impressment) because they needed men for their war against France. Things came to a head on 22 June 1807 when the HMS Leopard stopped the USS Chesapeake off the coast of Norfolk, Virginia demanding to board in search of four deserters. The Americans refused, so the British opened fire – killing 4 and wounding 17.

The Chesapeake surrendered and the British took back the deserters, executing one of them. In their defense, they considered any citizen who became American to still be a British citizen. In their eyes, they weren’t kidnapping anyone, only taking back valuable subjects.

The British also armed the native Indians to harass colonists and slow down their westward expansion. Finally, their ownership of Canada meant that they would always remain a threat to US independence and sovereignty.

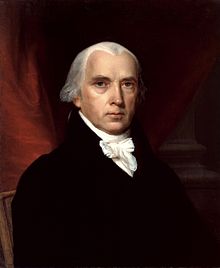

On 1 June 1812, President James Madison addressed the US Congress and urged them to declare war. This was no easy matter, since Britain was a superpower, while the US was a new country that didn’t even have an army – merely a largely untrained militia.

Across the Atlantic, the British parliament banned impressment on June 16, but it took a while for the news to reach America. On June 18, the US Congress finally came to a decision – and thus began the War of 1812. Their first order of business was to invade Canada, which turned out to be an embarrassing failure.

To everyone’s surprise, however, they scored a victory at the Battle of York (now Toronto) on 27 April 1813. Over the next three days, the Americans burned and looted the city, destroyed the Legislative Assembly, and stole the Parliamentary Mace of Upper Canada (which was only returned in 1934). Emboldened, they went on to attack Port Dover from May 14 to 16, razing it to the ground, and sealing the fate of Washington.

Napoleon was finally defeated in April 1814, leaving the British free to avenge this insult. Their treasury was exhausted, and their troops were devastated, so they weren’t interested in retaking America, only punishing it. The man put in charge was Vice Admiral Sir Alexander Cochrane, Commander-in-Chief of the Royal Navy’s North America and West Indies Station.

Cochrane raided the Atlantic seaboard to draw American troops away from Canada. That done, he ordered Rear Admiral George Cockburn to attack Baltimore, Washington, and Philadelphia, but Cockburn suggested Washington for greater impact. Cochrane agreed.

Washington’s only defense lay with its under-equipped and badly trained militia under William Henry Winder, a soldier and lawyer who did the best he could with what he had. Winder positioned his men at Bladensburg, some six miles from Washington on the eastern branch of the Potomac River on August 24. Facing him were veterans of the Napoleonic Wars under Major-general Robert Ross.

The Americans stood no chance. Winder ordered a retreat which turned into a route. Legend has it that the Americans ran so fast that the British suffered heat stroke trying to catch up. Now nothing lay between them and the capital.

The US government fled, while Madison spent the night in the town of Brookeville, now called the “US Capital for a Day.” First Lady Dolly Madison received word of the invasion and stayed in the White House long enough to save what valuables she could, including the official portrait of George Washington.

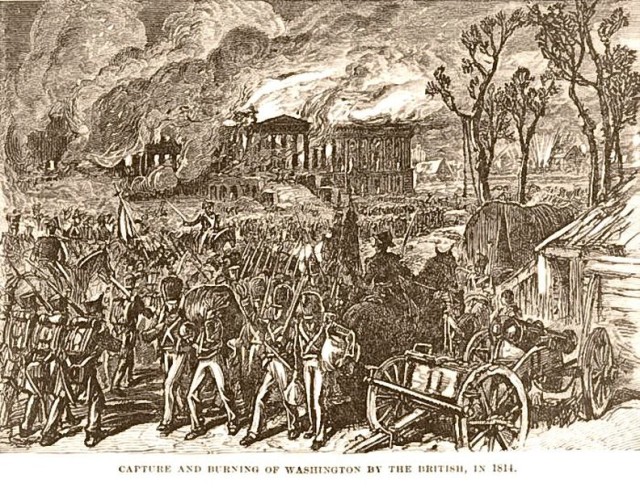

Four thousand British troops arrived at the capital that evening. Ross entered first at 8 PM to offer the remaining inhabitants his terms of surrender, but someone shot at him from a house on the outskirts. They missed him, but everyone inside was slaughtered before the house was burned.

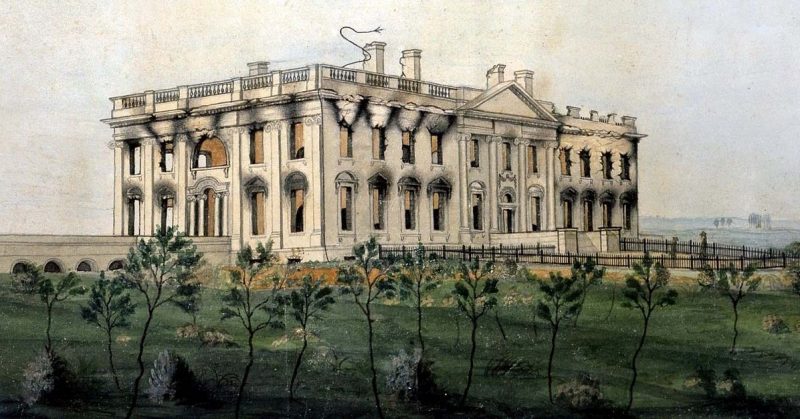

Ross convened a mock legislation, and everyone agreed that the city was to burn. First to go was the Senate House. Next, they went to the White House (then called the President’s Palace) at 10:30 PM and found a dinner set for 40 people. Ross and his men dined on that, then looted the building. A search of the office found Madison’s love letters to his wife, which Ross pocketed before razing the building.

Cockburn also ordered the office of the National Intelligencer paper burned because they had written badly of him, but some women begged him not to because they lived next to it. Acceding to their wishes, he had his troops tear it apart and destroy its equipment.

The following morning, the Library of Congress was in flames, as was the House of Representatives, the Treasury, the War Office, the Arsenal, and the Dockyard. Three rope factories met a similar fate, as well as a bridge on the Potomac, a frigate, and a sloop.

At 2 PM, things changed. A strong wind broke out suddenly, followed by a downpour which put the fires out. As the rain eased up, a tornado formed and smashed through Constitution Avenue lifting two cannons and dropping them many yards away, leaving people dead in its wake.

Then it stopped. Cockburn turned to a dazed resident and asked if this was typical American weather, to which the woman replied that it was god’s punishment upon the British. The admiral snorted and pointed out that god had done far more damage to the city than his men had, before riding off. The British suffered only one fatality from the tornado and six injured.

Many Americans urged the president to relocate the capital, but he insisted that it remain in Washington. Though badly damaged, the White House was made of stone and rebuilt, though not in time for Madison to move back into.