The term Pyrrhic victory can be used where someone technically “wins”, or achieves their objective, but the cost to do so made the victory almost not worth the trouble. The term is most often applied to warfare where a victory is won, but at such a high cost to the victor that they may rethink their goals, or they may lose strategic advantages that lead to them ultimately losing the war they are in.

The ramifications of Pyrrhic victories could take several years to actually appear, or the victory could be costly but ultimately still lead to an overall victory. Here are a few key Pyrrhic victories of history.

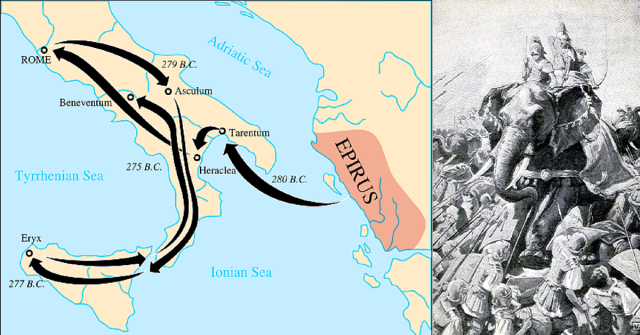

280-275 BCE: Heraclea, Asculum, Beneventum

These three battles are lumped together because they are collectively the origin of the phrase “Pyrrhic victory” comes from. The battles were part of the Pyrrhic War between the well-known general Pyrrhus of Epirus and the fledgling Roman state. Pyrrhus had invaded southeastern Italy and moved against the Romans expecting his well-organized, professional army to make quick work of the almost barbarian and tribal Romans.

At the eve of the first battle, Pyrrhus was surprised when he saw the strict organization of the Roman’s marching camp and remarked that he was facing no mere barbarians. The ensuing battle of Heraclea was a decisive victory for Pyrrhus, who employed a tight phalanx formation with elephant charges. Though this win was complete, the Romans fought for a long time before they finally broke, causing disproportionally high casualties for Pyrrhus’ best troops.

The next battle of Asculum was a similar result; the Romans attempted to repulse the elephants with impressive war wagons but failed. The Romans withdrew to higher ground and fought on until the two sides had to withdraw. The Romans definitely were worse off in the loss, but Pyrrhus lost thousands of men and many good officers.

When he was congratulated on his victory by one of his officers, he reportedly responded with: “If we are victorious in one more battle with the Romans, we shall be utterly ruined” (there are multiple varying translations).

Pyrrhus’ words would prove prophetic for, after a detouring campaign in Sicily, he fought the Romans again at Beneventum. The battle of Beneventum has been claimed as either inconclusive, a Roman victory and as a victory for Pyrrhus. The Romans were finally able to repulse the elephants and send them rampaging through Pyrrhus’ lines.

Pyrrhus could not take the Roman positions but seems to have maintained his army’s cohesion. The battle resulted in likely over ten thousand casualties for Pyrrhus and nearly as many for the Romans. Pyrrhus simply could not expect to continue if this was the amount of loss he could expect for a battle that gave no real strategic gain and so he left Italy for good, leaving the Romans free to claim it as their own.

480 BCE Thermopylae

Jumping back a bit, the battle of Thermopylae was a Pyrrhic victory before the term even existed. Almost everyone knows the basic story of the horde of Persians being fended off by the 300 Spartans and their allies. Over several days around 7,000 total Greeks held out and caused heavy losses to Xerxes’ troops, including his most elite fighters.

Xerxes seems to have had around 200,000 men and lost as many as 20,000 of them. He eventually trapped the Spartans and killed almost all of them (one Spartan and many of the other Greek allies escaped). The battle gave the Greeks hope, a feeling that though they were outnumbered, one Greek warrior was worth several of the best Persians.

The will of the Greek nations to continue the fight under all sorts of unfavorable circumstances was sparked by the engagement at the hot gates of Thermopylae. The battle cemented the reputation of the Spartans as the stoutest fighters in all the land and all of the Greek soldiers wanted to live up to their example.

The lone Spartan survivor was so ashamed of his survival that he went on an ultimately fatal rampage during the later Persian ousting battle of Plataea to reclaim his honor. The Persians could not hope to defeat such a unified and determined foe after Thermopylae.

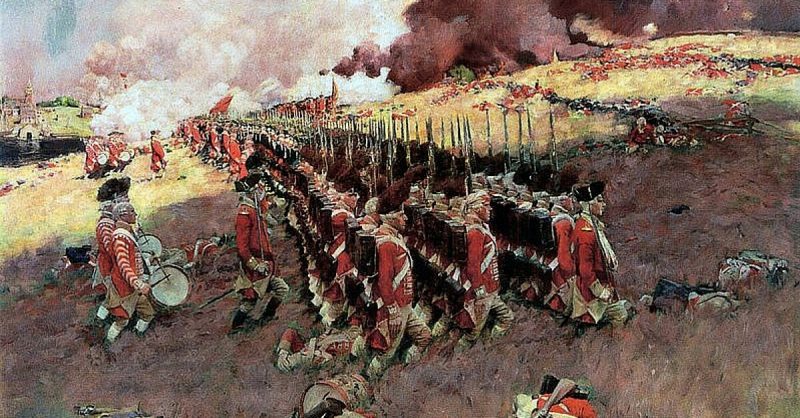

1775 Bunker/Breed’s Hill

“A few more such victories would have shortly put an end to British dominion in America.”

These were the words of British general Henry Clinton after the battle of Bunker Hill.

Bunker Hill was a battle fought during the Colonial’s siege of British-controlled Boston. In an effort to secure Boston harbor the British set out to take Bunker and Breed’s Hills which prompted their fortification by the besieging colonials. Breed’s hill was heavily fortified and that is where many of the British regulars were sent.

The British landed largely unopposed on the peninsula and marched straight up as well as around Breed’s Hill. The fortified militia gunned down the tight British formations coming up the hill while the British attempting to circumvent the position were repulsed by hastily built, but effective fortifications.

Three attacks were launched against the colonials with the British incurring heavy losses, particularly among the officers as they were specifically targeted. Eventually, the Colonials ran low on ammo resulting in the iconic command “don’t fire until you see the whites of their eyes” though that may not have actually been said during the battle. once the colonials ran completely out of ammo they were repulsed by the British but led an orderly retreat out of the peninsula.

The British had won, but at the cost of over 1,000 killed or wounded, compared to less than 500 for the colonials. The British lost dozens of officers, including two majors and a lieutenant colonel. The battle was a loss for the colonials but gave them hope that they could stand up to the powerful and professional British army. The British were eventually forced out of Boston as well.

1939-40 The Winter War

They say you should never invade Russia in the winter, well it could also say, you should never invade Finland in the winter. Russia decided to do just that in late November 1939. The invasion started based off of Russian claims for nearby territory and a desire to have protection for their city, Leningrad, so close to the border, though Russia may have had their sights set on conquering or controlling all of Finland.

Though not uncivilized by any means, Finland was given little hope at the outset; Russia had vastly greater numbers of men, aircraft, and tanks. The tide quickly turned as the Russians entered Finland. Though the war front was vast, there were few points where an army could realistically push through.

The Finns were at home in their harsh winter environment and used white camouflage as well as skis to ambush Russian columns either in sporadic incidents or as part of larger battles. The temperature dropped as low as -45 Fahrenheit and many Russians were seriously wounded or killed simply from frostbite.

Russian morale was terribly low while Finnish spirits were high. The Soviets were thwarted several times but eventually pushed through and forced peace talks. Russia ultimately gained a sizable chunk of Finnish land but paid a high price in manpower as well as international reputation.

The Finns had a high amount of national pride, being able to at least preserve much of their nation against the giant nation of the Soviet Union. Finland lost around 70,000 killed or wounded while Russia lost over 300,000 men. The war was continued as a smaller part of WWII with similarly skewed casualty rates for the Russians though this time they lost as many as 800,000 men.

By William McLaughlin for War History Online