Early on in the Napoleonic Wars, Napoleon had grand plans to invade Great Britain. Conquering that region would leave him free to pursue other conquests and remove the largest rival naval power. Unfortunately for Napoleon, his juggernaut of a land army was stopped by the Royal Navy that dedicatedly guarded the narrow English Channel. Napoleon needed only to control Channel for long enough to get his army across and he was as confident of victory as the British were terrified of defeat.

To keep Napoleon from even having a chance of temporarily controlling the Channel, the British split their navy up to blockade many of the ports that contained the French navy. The series of movements between Napoleon attempting to seize control of the Channel and the British preventing him would be known as the Trafalgar campaign, lasting through most of 1805.

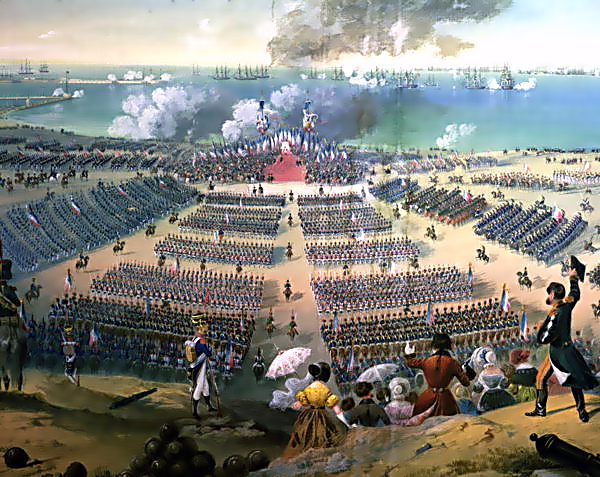

Napoleon finally decided to have his navy and the allied Spanish navy form a massive overpowering force that he hoped to use to sweep the Atlantic coast and clear the Channel. Though Napoleon seems to have lost his intention to secure the Channel the fleet was gathered on the Atlantic side of Spain at the port of Cadiz. Close by was the large Royal Navy under Lord Horatio Nelson.

Lord Nelson had a spectacular career prior to Trafalgar, having fought admirably and with aggressive tactics at the Battle of the Nile, where he defeated a larger French naval force. Nelson had experience from the age of twelve and fought in numerous wars, losing an eye and an arm in the process. Seeing a massive amount of French and Spanish vessels, Nelson sought to fight a decisive battle to cripple French sea power.

Nelson had 27 ships-of-the-line under his command. As warships of the time were built to hold as many cannons of they could, ships are often measured by total cannons classifying them as first, second, third rates and other classes such as frigates. Nelson had three 100 gun first rates including his flagship HMS Victory, four 98 gun second rates, and twenty-third rates of varying size.

Ship-of-the-line refers to the role of the ship in a line of battle, the standard tactic of the day was to form single parallel lines and sail past an opponent, trading broadsides until one side broke. These were often less than decisive engagements won more by the size of the navy than by talent.

The French commander, Pierre-Charles Villeneuve, and Spanish commander, Federico Gravina, had four first rates, and no second rates. Their first rates were much bigger than their British counterparts, however. The largest ship of its day, the Santísima Trinidad, had over 136 guns (as many as 140, the extra being rather smaller in size). Two others had 112 guns and the other 100. Twenty-nine third rates rounded out their force giving them a sizeable ship advantage and around 500 more cannons in total.

Villeneuve suspected that Nelson might try some orthodox tactics if they forced a battle, but could not hope to do anything other than standard formations with his fleet. Many of the men were new to sailing and his officers were far too inexperienced, so Villeneuve sent his fleet out first in three columns, then into a line forming a disorganized fighting line stretching several miles.

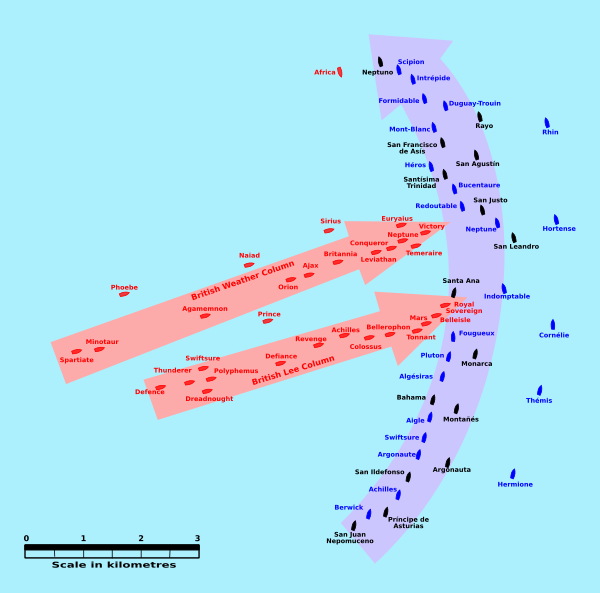

Nelson had formed a simple, but ingenious plan to hit the enemy line perpendicularly with two of his own parallel columns. The northern column under Nelson would aim straight at the middle of the French/Spanish line while the southern column would cut through the rear. The goal was to muddle the lines and create sporadic ship-to-ship combat where the superior skill of the British sailors could win in isolated engagements. By aiming at the center, Nelson hoped to take the enemy front out of the battle as they would be sailing away and turning around to support their rear would take a long time, hopefully long enough for Nelson to secure victory without them fighting.

On the morning of October 21st Nelsons plan began perfectly; they were even aided by very low winds, giving the British plenty of time to prepare and get into position. Nelson ordered a flag signal to be displayed to his fleet reading “England confides that every man will do his duty”. The word confides was changed to “expects” as that word could be made with one set of flags rather than having to be spelled out.

Nelson on the Victory led the northern column while commander Collingwood in the 100-gun Royal Sovereign led the southern column. It was on the approach that the slow winds would be detrimental to the approaching British as the perpendicular approach allowed the full allied broadsides to be fired with the British unable to effectively retaliate with just the bows facing the enemy. The Victory took an amazing amount of damage, with much of the mast destroyed, as well as the wheel, requiring steering to be done below deck. Dozens of sailors were killed before they closed. Despite the damage done, it was less than could have been expected as the French crews were largely untrained resulting in scattered and badly aimed broadsides.

After nearly an hour of approach, the two columns of the Royal Navy cut through the curving line of French and Spanish ships. Curiously the British ship HMS Africa had been far out of position before the battle and approached from the direction the Allied (French, Spanish) force was traveling and thus exchanged broadsides in the traditional manner of battle. The rest of Nelson’s force clustered around the allied ships and used their superior training to great effect.

Nelson knew that his men’s talent and morale were far higher, and his captains had more experience. Prior to the battle, he told his captains that “No captain can do very wrong if he places his ship alongside that of the enemy”. To illustrate the gap in skill, it was said that the British could unleash three broadsides in five minutes compared to two for French crews. Though it seems trivial, it meant that over the hours of battle the disciplined British were able to fire off several dozen more broadsides.

The masts of the Victory and the French Redoutable quickly became tangled and Nelson was shot during a boarding struggle. The bullet traveled through his shoulder and into his spine, fatally wounding him. His men fought off the boarding, aided by a passing ship that raked the enemy deck and the Redoutable would soon surrender.

Within three hours the massive Santísima Trinidad was surrounded and also surrendered. Many other French and Spanish ships were soon captured and the Allied front had eventually turned around only to see imminent defeat, and simply sailed away after light skirmishing. The British had suffered roughly 1,500 dead or wounded but kept all of their ships. The allied forces had ten ships captured and one destroyed, with over 13,000 dead, wounded or captured. Nelson passed away shortly after hearing the news of victory.

A storm soon after the battle resulted in some captured ships being stolen back or sunk, but the British had achieved their goal of crippling the French navy. The remaining allied ships would later be captured at the battle of Cape Ortegal. Napoleon would later attempt to build a massive fleet as large as 100 ships-of-the-line but he crumbled before this could be completed. The loss of his fleet marked the decline of Napoleon and a failed Russian invasion in 1812 was in part due to the absolute failure to gain advantages at sea.

Lord Nelson was brought back to London for burial where he was simultaneously mourned and celebrated. The greatest fear of the British, the invasion of their homeland, was gone thanks to the bold tactics and leadership of Nelson. Many were torn by the grief of losing such a talented and loved commander, and his funeral was one of the most remarkable of all British history. Nelson banked on the skill of his men and used aggressive tactics against a much larger force to force a decisive victory. He is remembered today as one of the greatest British commanders of all time.

By William McLaughlin for War History Online