Though America became independent of the British Empire in 1776, the British didn’t actually leave. Where the United States of America ended and where British-America began took far longer to resolve, resulting in border disputes which sometimes turned into skirmishes.

In 1859, America stood on the brink of civil war. As it did, another battle with Britain loomed because of a pig. A Cornwall Black one, to be precise. The whole thing was so complicated that even the Germans got involved.

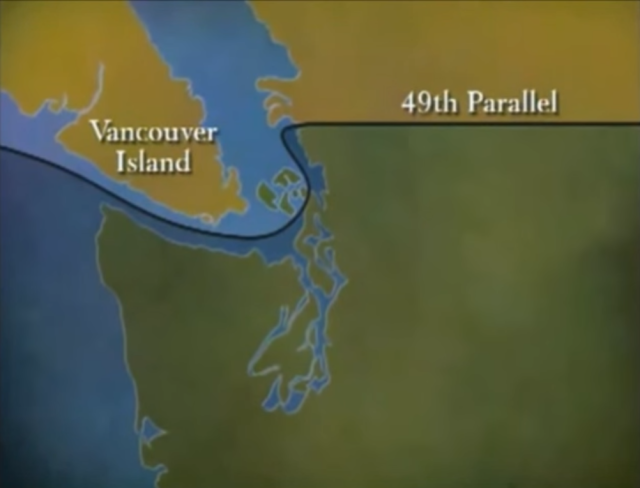

It all started with the Oregon Treaty of June 15th, 1846. The British and the Americans decided that the 49th parallel north of latitude would be the dividing line between them. Everything south of that line would go to America, while everything north would go to Britain.

Further west in the Pacific Ocean is Vancouver Island. And that’s where the problem began for the southern tip of the island dips below the 49th parallel. It was therefore decided that the maritime border would run down the middle of the Strait of Georgia which separates the mainland from Vancouver Island.

Everything west of that line would go to Britain, including Vancouver Island, while everything east of it would go to America. It seemed simple enough.

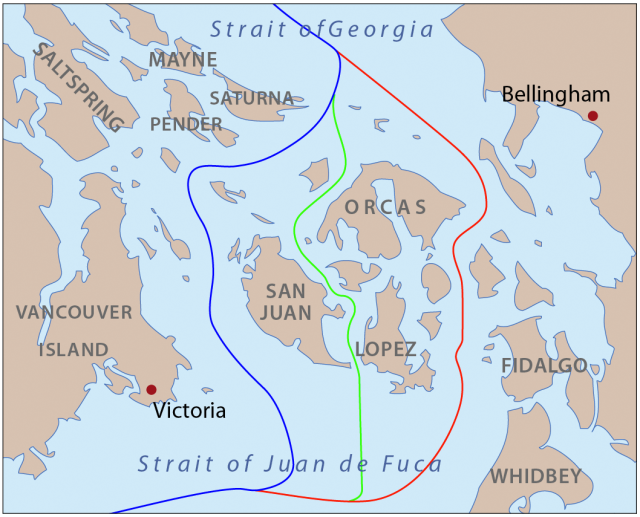

If only. Because several islets lie within the Strait of Georgia, there isn’t one strait, but two. Smack in the middle are the San Juan Islands – so named because the Spanish had dibs on them before handing their claim over to the Americans.

To the west of the San Juan Islands is the Haro Strait, while to the east lies the Rosario Strait. The British wanted the maritime boundary in the latter so they could also claim the San Juan Islands, while the Americans wanted that boundary in the Haro Strait for the same reason.

Part of the problem had to do with the fact that they were relying on inaccurate and outdated maps. By 1859, and despite better maps, they still couldn’t agree on where the maritime border lay. As a result, many of the islands remained in contention.

The Oregon Treaty had displaced the citizenry of both sides as British citizens had to move north of it, while Americans had to move south. As for the disputed islands, it was agreed that neither side would militarily occupy any of them.

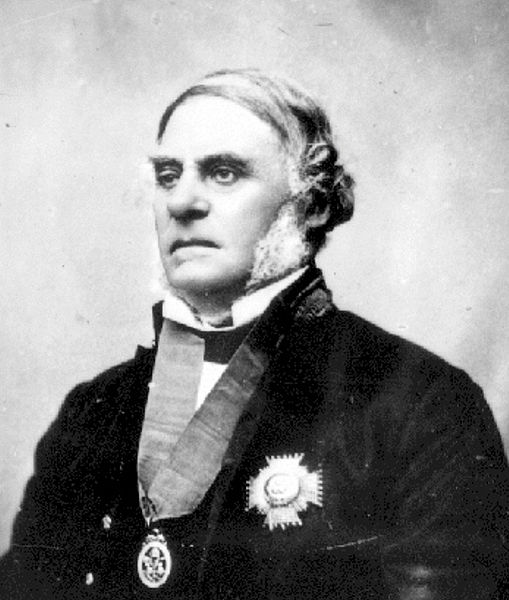

Sir James Douglas, governor of Vancouver Island and British Columbia, was especially unhappy. The treaty had cost the British their Fort Vancouver, which had served as the headquarters of the lucrative Hudson’s Bay Company.

So Douglas granted the company permission to operate the Belle Vue Sheep Farm on the southern end of San Juan. And because nothing had been set, a number of Americans had also settled there.

Those Americans survived by growing their own crops. And thus began the countdown to what history calls the “Pig War” or the “Pig and Potato War,” because potatoes were also involved.

Lyman Cuttar grew potatoes and was annoyed when a Cornwall Black came along and helped itself to his crop. The pig belonged to Charles Griffin, an Irishman who worked for the Hudson’s Bay Company. But when Cuttar complained about the creature, Griffin shrugged and accused him of squatting on British land.

On June 15th, 1859 the animal again pigged out on Cuttar’s potato patch. Fed up, the farmer shot the damned thing, but when he offered Griffin $10 in compensation, the Irishman demanded $100, instead.

Legend has it that Cuttar insisted he shouldn’t have to pay anything since Griffin couldn’t keep his pig out of the potato patch. To which Griffin replied, “It’s up to you to keep your potatoes out of my pig.”

Unable to reach an agreement, Griffin went to the British authorities who threatened to arrest Cuttar. There were about 25 American settlers on San Juan Island, so they appealed to the US government for help.

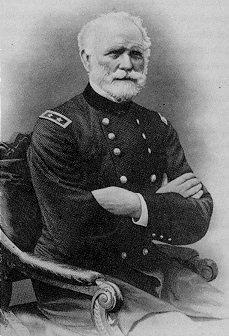

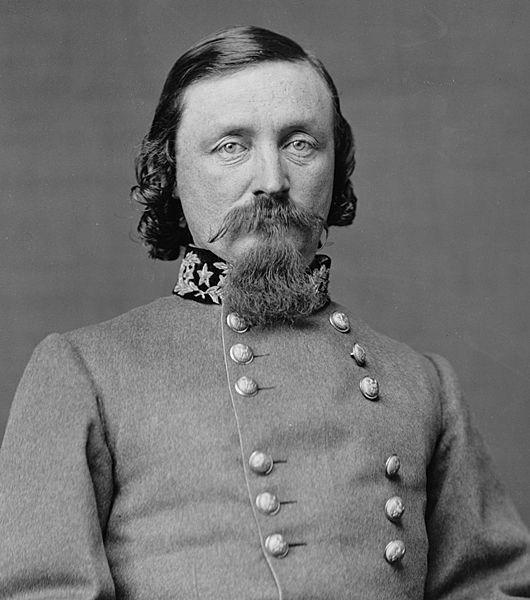

Unfortunately, their appeal reached a famous hot-head – Brigadier-General William Selby Harney, a veteran of the Indian Wars. It got worse. On July 18th, Harney dispatched another hot-head to the colonists – Captain George Edward Pickett (the man who later led the futile Confederate charge at the Battle of Gettysburg).

Pickett arrived on the island on June 22nd with 66 soldiers of the 9th Infantry. He then decreed that no law applied to the island save those issued by the US government. In so doing, he assumed official jurisdiction over San Juan Island and violated the terms of the Oregon Treaty.

Douglas, yet another hot-head, responded by sending over three Perseverance class 36-gun steam frigates. The HMS Tribune arrived at San Juan on June 24th and positioned itself directly below Pickett’s position. The other two kept their distance in case the Americans had some nasty surprises of their own. As the Tribune came to a stop, its gun ports opened.

The ship’s captain offered Pickett joint occupation of the island till the matter was resolved, but Pickett refused. The Americans sent for reinforcements, so the British did likewise.

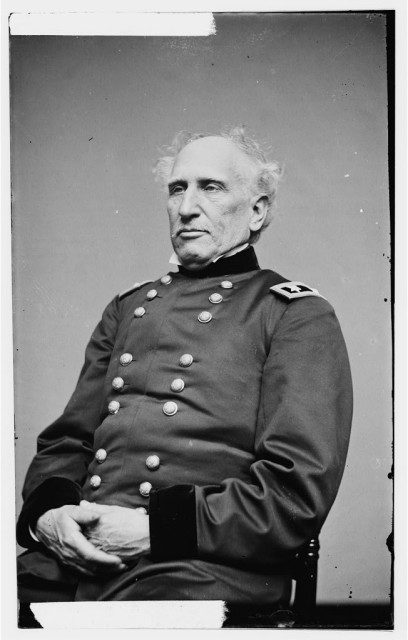

Colonel Silas Casey reached the island on August 10th, giving the American side a total of 461 men with 14 canons. And the British? Five warships with a total of 2,140 Royal Marines and 70 guns.

Interestingly enough, neither the American president nor the British prime minister were even aware that their two countries were on the verge of yet another war. President James Buchanan, Jr. only found out on September 3rd and he wasn’t happy since he was barely holding the country together.

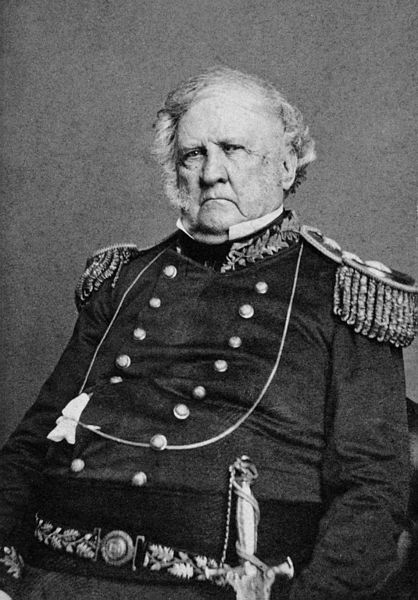

His solution was to send over Lieutenant General Winfield Scott – hero of the Mexican-American War. Scott was called “The Grand Old Man of the Army” because he was 73-years-old and obese. But he was also called “Old Fuss and Feathers” because of his bearing, discipline, and manners.

Scott arrived on San Juan on October 17th and was relieved to discover that neither side had yet fired upon the other. He convinced Douglas to send away most of his marines, then sent Harney to a minor outpost in St. Louis.

The two sides occupied the island with a force of 100 men each, with the British camped to the north and the Americans to the south. They remained friendly for years till the border issue was finally brought before the German Emperor Wilhelm I.

On October 21st, 1872 the Germans decided that the border lay in the Haro Strait, giving the San Juan Islands to the Americans. The British accepted the decision gracefully and withdrew from the island on November 25th of that year.

The Union Jack still flies over the site of the British camp, but it’s now raised and lowered by American pork… sorry, park rangers.