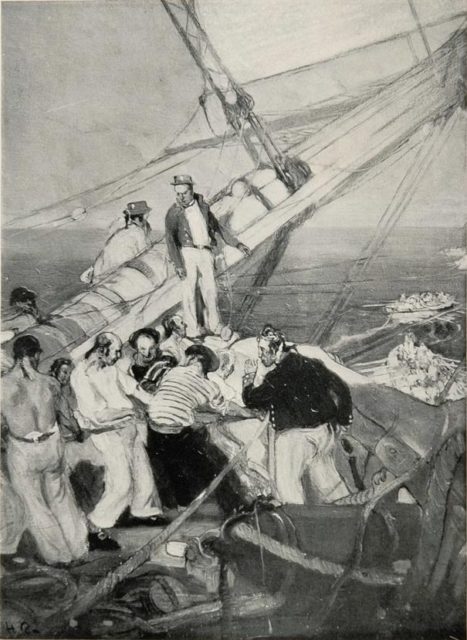

Sweat poured down the brows of eight American sailors, their white-knuckled fists gripping long oars. The bosun bellowed at them to pull for their lives as the faint whistle of a cannon ball was heard over the commotion behind them.

It fell short, sending a pillar of water towards the sky, and was immediately answered by an American cannon spewing smoke and iron in return.

The sailors were some of the many men, selected from the crew of USS Constitution (44 guns, and 450 souls), tasked with kedging; pulling their anchor out forward and dropping it. Thus allowing the large ship to pull itself along a line attached to it.

Behind the Constitution crept HMS Africa (64 guns), HMS Aeolus (32 guns), HMS Shannon (38 guns), HMS Belvidera (36 guns) and HMS Guerriere (38 guns).

Kedging, wetting sails, and firing at every possible opportunity, the five ships of the English squadron strained towards the loan American frigate, whose crew fought desperately to escape what they knew was certain defeat.

After 57 hours of arduous struggle, Constitution slipped below the horizon, finally free from her pursuers. She made as much speed as she could muster towards Boston, safety, and home.

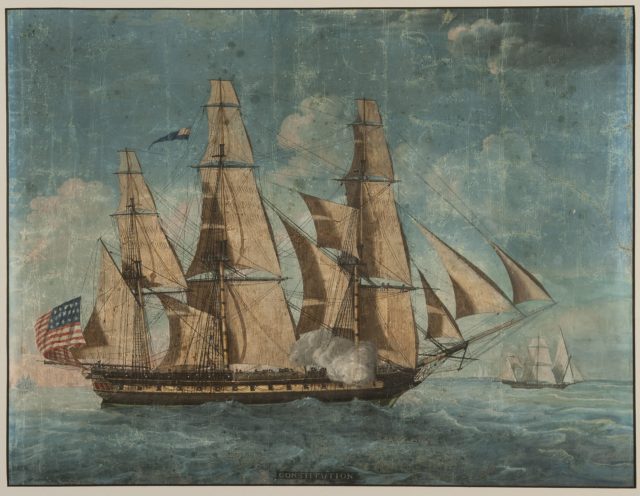

That was how the War of 1812 began for the crew of USS Constitution, a frigate built in 1797. She was one of only six frigates in the tiny United States Navy, far outnumbered by the Royal Navy. Constitution and her sisters were not outdone.

They were some of the most advanced ships on the water at the time, thanks to their designer Joshua Humphreys.

He had created a design which was thinner, longer, and stiffer than anything else in the world. This allowed his ships to achieve greater speeds, without sacrificing the number of cannons carried or hull strength.

When war broke out in June 1812, this new design had not been tested against an adversary of equal power. On July 12th she set sail from Annapolis, on a voyage which would secure her a place in American memory forever.

She was searching for an American squadron led by Commodore John Rodgers when she discovered the ships she was approaching were English, initiating her nail-biting escape. She finally made Boston on July 27th but knew full well that those five English ships would be close on her wake.

Her Captain, Isaac Hull, took on enough supplies for a six-month voyage, replenished their water (which they had thrown overboard during the chase), and prepared to set sail as soon as possible.

The great ship and her 450 man crew set out again, on August 2nd, bound for the prize-rich shipping lanes off Halifax, in Nova Scotia.

She prowled the frigid waters of the Grand Banks, capturing three British merchant ships. Captain Hull was not certain if Boston was still a free and open port, or if the British had blockaded it.

He could not risk sending a crew with a prize English merchant ship, only to have it recaptured. Every ship he took had to be burnt, once the crew was safe aboard Constitution.

While cruising, Constitution met almost no resistance, until on August 18th, sails were sighted to her south. She let fly all of her canvas, beat to quarters and chased after what appeared to be an English sloop of war and a convoy. After a two hour chase,

After a two hour chase, Constitution finally closed on the smaller vessel. Upon boarding her, both ships discovered they had misidentified the other; the Constitution found her prey was an American privateer, by the name of Decatur.

Decatur saw that it was an American frigate which had chased her, not the English one which she had evaded the day before.

Suddenly the atmosphere onboard Constitution changed, her carefree days of raiding convoys was over. There was an English frigate about, and the Americans could not resist the opportunity to prove what their ship could do. They beat to quarters again and set sail on a southerly course.

The next day, after many hours of hard sailing, a sail finally appeared. At 4 bells (2pm), the faint outline of a ship was sighted on the horizon, directly south.

By 6 bells (3pm) she was identified as a frigate (likely the same which had chased Decatur). Both ships hoisted battle sails (topsails and jibs) and cleared their decks for action. Tension must have filled the air.

The two massive war machines raced towards each other, but it was another hour before they were close. Each man stood by his gun, looking to the captain of the gun crew, waiting for the precise order to fire.

As the two ships closed, the English frigate raised three English flags at 8 bells (4pm).

Five minutes later a rippling report of 16 cannons broke the relative silence. The English frigate, now recognized as HMS Guerriere, one of the five ships which had chased Constitution barely a month ago, unleashed her starboard broadside.

16 plumes of water shot up in front of the American ship; all had fallen short. Guerriere turned, bringing her other side to bear, and unleashed another rippling broadside.

Again they fell short. It was now close to 2 bells (5pm).

While Constitution approached, Guerriere turned back and forth, trying to find a good position for an effective shot. For nearly an hour the ship danced about until Constitution was close enough for a pistol shot.

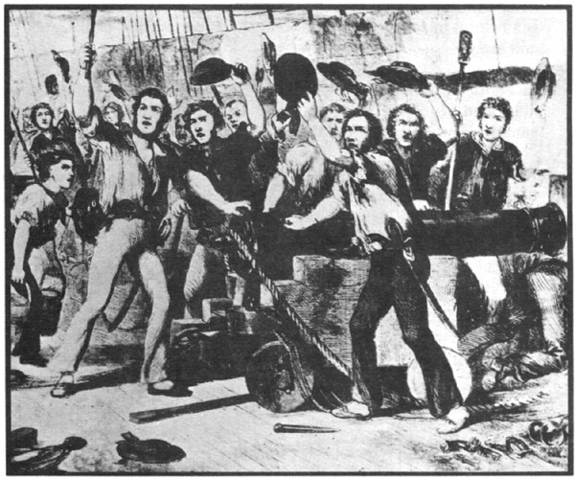

The British fired first. A massive broadside, over 500 pounds of iron, smashed into Constitution’s side but the thick planking and dense wood withstood the barrage.

One sailor was heard to cry “Huzzah! Her sides are made of iron!” as one ball rolled harmlessly down the fortress-like walls. The American ship opened fire, its cannons belching flame, and metal. The two floating hulks exchanged broadside after broadside. While

The American ship opened fire, its cannons belching flame and metal. The two floating hulks exchanged broadside after broadside. While Constitution stood high, whole and nearly undamaged, the Guerriere’s mizzenmast fell, collapsing in a heap of line, canvas, and wood.

The English ship turned, wrapping her bow into Constitution’s rigging, entangling the two.

Boarding parties readied themselves from both ships, but no one could cross the narrow beam. The English gun crew fired shot directly into Captain Hull’s cabin, setting it ablaze.

Soon the sea forced both ships apart, their rigging straining and snapping as they broke away. Guerriere’s remaining two masts broke apart, pulled down by the tangle of ropes. Constitution pulled away, making quick repairs.

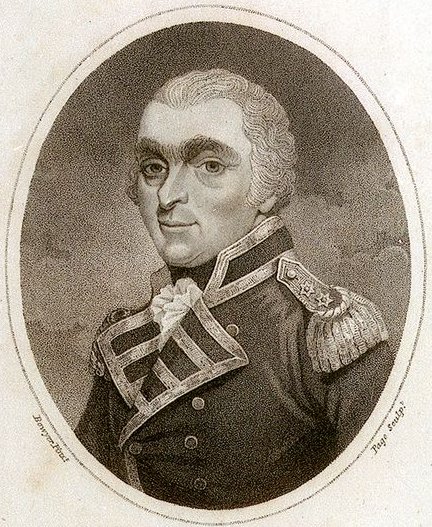

Soon she sailed back up to her crippled foe, preparing to land the final blow. Guerriere fired a single cannon, acknowledging defeat, and asking for mercy. Captain Hull obliged, sending a Lieutenant over to accept. The Lieutenant asked if Guerriere had struck her colors.

Captain Dacre, in command of the English ship, reportedly said “Well, Sir, I don’t know. Our mizzen mast is gone, our fore and main masts are gone – I think on the whole you might say we have struck our flag.”

The Lieutenant returned to Constitution with Dacre, who offered Hull his saber, the traditional sign of defeat. Hull refused, saying that the Englishman had fought as well as could be expected and he had nothing but respect for him.

Now Hull was faced with a problem. He had a British frigate, which could be captured and repaired but this might risk a recapture as their travel would be slow. He opted instead, to take every man on board captive, and burn the Guerriere .

He sailed to Boston, to bring news of one of the first great victories of the war, to a public that was already weary of English blockades, and constant fear.

The Constitution has become one of the most iconic symbols of the Unites States Navy. Following her return to Boston, she continued to fight until the end of the war in 1815.

Today, after numerous restorations, she sits as the oldest commissioned warship still afloat and, as of 2015, the only commissioned US warship to have sunk an enemy vessel.