The conventions for naming American submarines depends on the time when they were commissioned and the type they were. Today, submarines are generally named after states or cities, or sometimes great Americans.

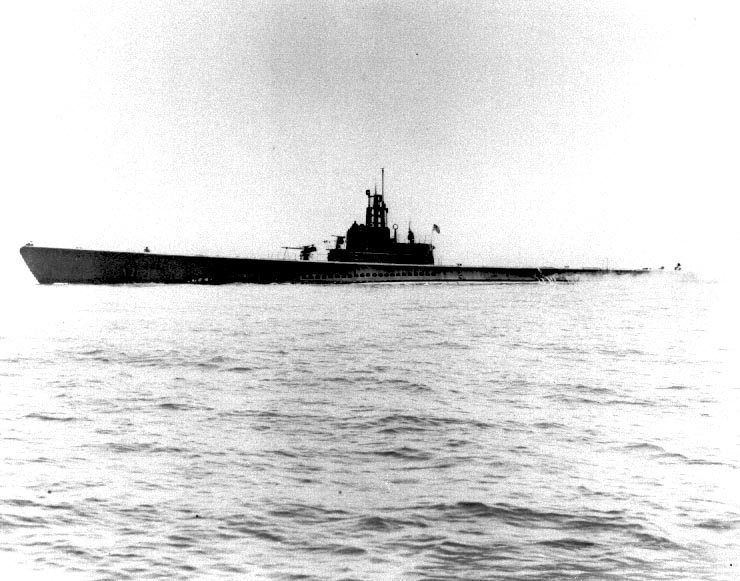

During WWII, US submarines were named after fish or sea mammals, and their numerical designation was prefaced by the letters “SS”, for “steam screw”. SS-191 was the USS Sculpin, the first of three boats to carry the name.

The sculpin is an ugly deep-water fish with big bulging eyes to help it see in the depths. It also has specialized barbs in its fins and gills that not only allow it to anchor itself to the sea bottom, but also work to repel attackers. SS-191 very deservedly took its name from this tenacious deep-sea fish.

Commissioned in 1939, the Sculpin was an “S-class” submarine, of which there were ten. All of the subs in the class were named after fish or mammals whose name began with the letter “S”. The subs were powered by either direct-drive or diesel-electric engines/auxiliary battery and displaced 1450 tons surfaced and 2350 tons submerged.

https://youtu.be/MqllihZqzf4

They were 310 feet (about 94 meters) long and 26 feet (almost 8 meters) wide. They had a top speed of 21 knots surfaced and 8.75 knots submerged. The boats had an incredible 11,000 mile (17.7 kilometers) range and were able to remain submerged for forty-eight hours at two knots.

The subs were tested to 250 feet (76 meters), but sometimes were forced closer to 300 feet (91.4 meters). The crew consisted of 5 officers and 54 enlisted men manning eight 21-inch torpedo tubes and 24 torpedoes, one 3-inch deck gun, and a combination of .50 or .30 machine guns.

In 1943, the Sculpin was the chief boat in Submarine Division 43, a group of three submarines in the Central Pacific. They were stationed to defend the sea lanes approaching the Gilbert Islands, which was to be the site of the famous invasion of Tarawa in late November.

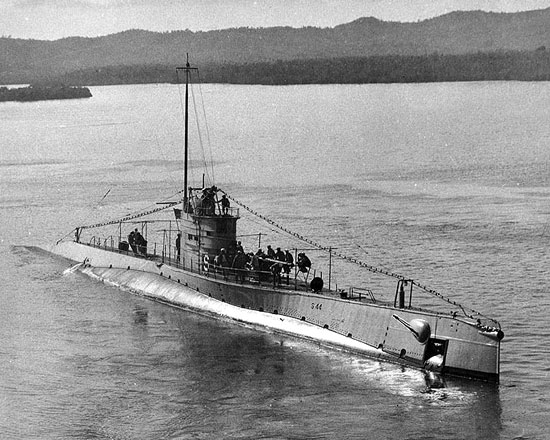

Commanding the 3-boat sub division was Captain John P. Cromwell. The captain of the Sculpin itself was Commander Fred Connaway. The two other boats with Sculpin were the Sargo-class boat Searaven and Balao-class sub Apagon.

Captain Cromwell, like many Navy men, was from a land-locked state: Illinois. Born in 1901, Cromwell graduated from Annapolis in 1924. He served in a variety of duties before the war, including on the battleship USS Maryland. In the pre-WWII Navy, a battleship was a desirable assignment, but Cromwell was drawn to the submarine force.

In 1936, Captain Cromwell was given command of his own sub, USS S-20. By the time war broke out in 1941, Cromwell had served not only as captain, but in a variety of staff positions in Washington as well as Engineer Officer for the submarines across the entire Pacific Fleet. He had fostered connections and was well-respected.

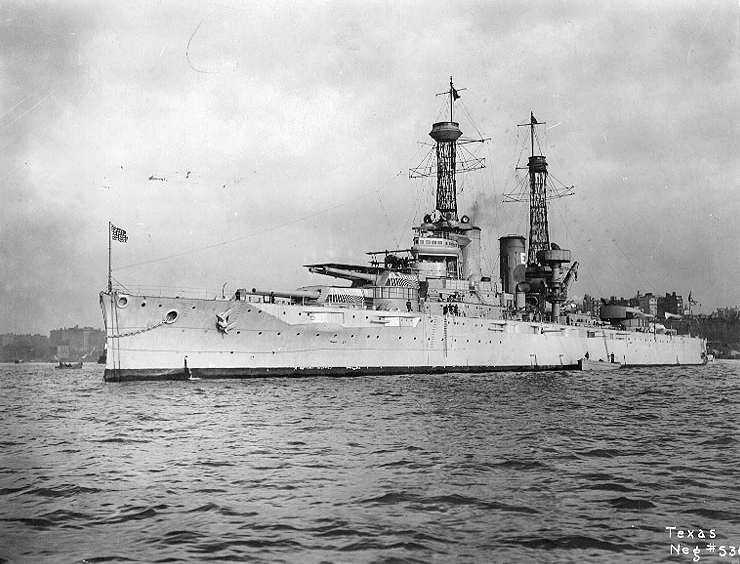

Commander Connaway was ten years Cromwell’s junior, but also from a land-locked state – New Mexico. After graduating from the Naval Academy, Cromwell served aboard the battleship Texas for two years, and then transferred to submarine school.

By 1939 he had commanded two subs, and at the start of the war was commanding sub S-48. In 1931 on a submarine voyage across the Atlantic, Connaway wrote to his mother, relating the conditions aboard the boat:

“For three weeks I am an engineer. Besides having two lectures a day and having to sketch the entire engineering plant and electrical system, and having to write up the lectures, and having to stand eight hours’ watch every day at the most unearthly hours in the fire room, temperature 130 degrees F, I don’t have very much to do except try to find time and a place to sleep.”

By November 1943, the Sculpin had undertaken eight war patrols. During those patrols, the men of the Sculpin had taken the fight to the enemy, consisting of eighteen Japanese ships, including one cruiser. Not all of the men aboard Sculpin had been on every mission, including Cromwell and Connaway, but many of them had some combat experience, and on the boats’ ninth war patrol.

This would be extremely important as both Commander Connaway and Captain Cromwell had not been on war patrol before. Both men had served on subs and the submarine fleet in a variety of ways, but neither had seen a war patrol in an active combat zone.

On November 16th, 1943, Sculpin, Searaven and Apagon took position near Truk, west of the Marshall and Gilbert Islands, protecting the sea lanes from any approaching Japanese ships.

The Americans had a number of serious advantages in the Pacific – and Commander Cromwell was in possession of some of them. He was privy to the knowledge that the Allies had broken both many of the German naval codes and the primary Japanese code (“JN-25” or “Purple”) as well.

He also knew the position of most of the subs in the Pacific and had detailed knowledge of the coming invasion of Tarawa. Additionally, the Americans, including Cromwell’s Submarine Division 43, knew where most of the Japanese fleet was, or was heading. The deployment of the three subs at Truk was intentional.

On the night of the 16th, Captain Connaway sighted a convoy of Japanese ships steaming at high speed in the direction of the Gilberts. In the darkness, Connaway drove Sculpin on the surface, parallel to the Japanese convoy, getting ahead of it in the early morning hours, then submerging in wait.

When dawn broke, Sculpin surfaced, but was spotted by a Japanese destroyer, which soon made right for it. Connaway ordered an emergency dive and took the boat as far down as possible. Inside the sub, Cromwell, Connaway and the crew of the Sculpin listened as the Japanese convoy passed overhead.

Believing they were clear, Connaway rose to periscope depth in the hope of catching the enemy convoy before it moved out of range. This time, another Japanese destroyer, the Yamagumo, was heading straight at him. Once again the Sculpin dove deep.

Many people have expressed the sentiment that war is “mostly boredom, punctuated by moments of terror”. Of all the moments experienced in war, perhaps none is more terrifying than being in a submarine while it is being depth-charged.

Unnaturally confined in a steel box in the first place, then sent under the waves, men in a sub are then subjected to oil-drum sized explosive charges on them in the hope that the explosions will crack open the hull of the submarine, and all aboard her will be sent into the deep ocean.

There are so many terrifying aspects to this that it is hard to single out just one, but many submariners who have been through a depth charge attack will tell you that among the worst things about it is the inability to shoot back – you are at the mercy of the enemy.

After hours of being attacked and searched for (the dreaded “ping” of sonar), Sculpin surfaced at noon. When the boat reached 125 feet, the depth gauge stuck. When the boat surfaced, it was rather abruptly, as no one aboard was quite sure how deep Sculpin was. In the conning tower, Connaway once again found himself staring at a Japanese destroyer heading right at him.

Screaming for an emergency dive, Connaway slammed the hatch behind him and the Sculpin descended once again. This time, eighteen depth charges fell near the boat in quick succession. One of the charges effected the subs’ ability to control its depth.

The boat rapidly dove past her maximum depth of 250 feet, heading to 300. Leaks appeared throughout the boat as rivets and seams began to give. Any deeper and Sculpin would crush – the water pressure of the ocean around her would simply cave in her hull like a paper bag.

Connaway and his crew managed to stop their descent, but only by powering through the water at full-power. This in turn gave the Japanese sonar-men above more noise with which to target the Americans. Eventually, one of two things was going to happen – neither of them good.

One, the sub could continue to try to make way under full power, but eventually fuel would run out, or the engines would be damaged beyond repair. Then the boat would stop, sink, and everyone in it would be crushed by the deep. Second, the enemy could easily score a fatal hit. The probability of either happening was very high.

That left one possibility: surface and fight it out as long as possible. That’s what Commander Cromwell and Captain Connaway agreed to do. When Sculpin blew her ballast tanks and surfaced, Captain Connaway and the gun crew ran out onto the deck to man the boats’ 3-inch gun. The first Japanese shell hit the American sub, killing Connaway in the conning tower and all of the men of the gun crew.

The boats’ second in command took over, and he ordered the boat scuttled – primed with explosives and sunk. The crew would abandon ship as best they could before their boat exploded. As difficult as that order was to give, one man had a worse decision to make.

Below deck, Commander Cromwell was faced with a choice – be captured and likely give up the secrets he held under torture, or…die in the ocean’s depths. Cromwell informed those around him of his decision and ordered them to abandon ship.

The dive officer, Ensign W.M. Fielder, elected to remain behind with Cromwell to help make sure the boat did indeed sink. A number of severely wounded men, knowing what treatment they would receive at the hands of the Japanese, also elected to stay behind.

Forty-two other men abandoned ship. Immediately they realized the stories about Japanese treatment of prisoners they had heard were true – one wounded man was thrown back into the sea to drown as the rest were brought into captivity.

Read another story from us: The End of the Rising Sun – The Japanese Surrender in Color

Eventually put aboard the Japanese carrier Chuyo for transport to a POW camp, the men of the Sculpin and others were torpedoed by the USS Sailfish, whose captain and crew were unaware of the POW’s aboard the enemy ship. Ironically, four years before, the crew of the Sculpin had rescued the crew of the Sailfish after an accident off the New England coast.

Only twenty-one men from the Sculpin survived the war. Cromwell was awarded the Medal of Honor, Connaway the Silver Star.