How does a conquering army overcome resistance from the local population? For the United States, the answer has often taken the form of the somewhat nebulous concept of “winning hearts and minds.”

Essentially, the United States tried to convince the native population that they have been liberated and that their quality of life has been improved by a benevolent American invasion.

One of the earliest efforts the United States made to win hearts and minds was really only carried out by half of the United States — or rather, two separate halves simultaneously.

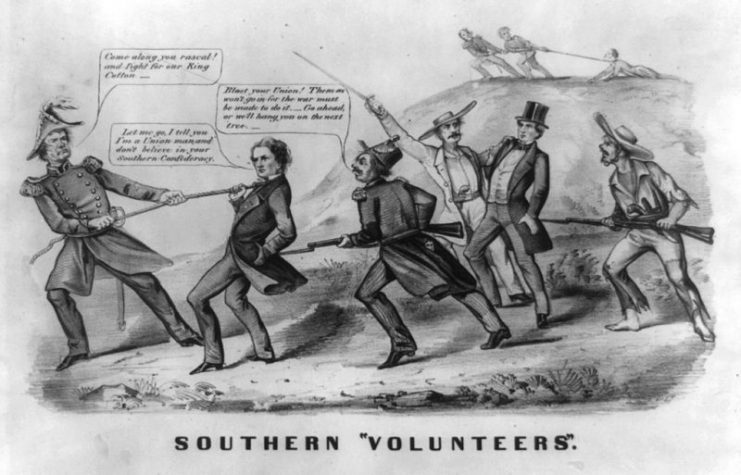

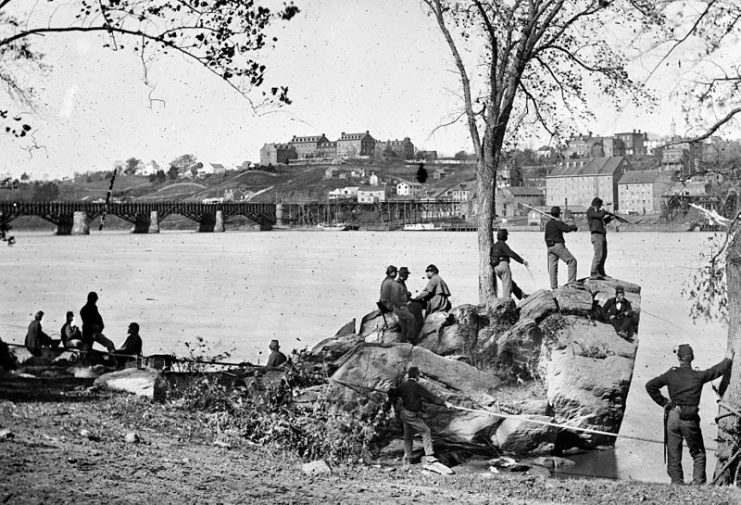

Both the North and the South during the Civil War expected to find massive numbers of friendly faces and new recruits when they entered the other’s territory. They expected to be able to approach the native population and win over many of those who were skeptical of their cause. In both instances, this strategy would utterly fail.

The Confederacy

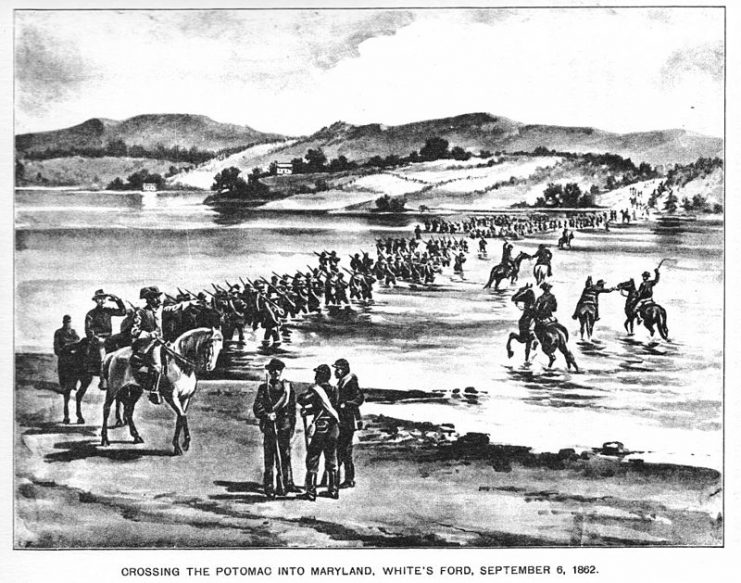

When Robert E. Lee invaded Maryland in 1862, he remarked to Jefferson Davis that “If it is ever desired to give material aid to Maryland and afford her an opportunity of throwing off the oppression to which she is now subject, this would seem the most favorable.”

On the assumption that citizens of the slave state would rise up to support him, Lee was less concerned than he should have been about his small numbers, insufficient ammunition, and difficult supply lines.

This assumption may have seemed reasonable given pro-confederate riots that took place in Baltimore only a year earlier. However, Western Maryland was far less friendly to the Confederacy. Despite Lee’s instructions to his men to pay for supplies instead of looting and to act amicably, he found little support either in terms of supplies or manpower.

The Southern pitch to pro-slavery and anti-war sentiments among Marylanders, combined with their attempt to show hospitality, simply did not convince civilians who now found themselves in the middle of the war thanks to the Southern advance.

The Union

The Union fared only somewhat better when it came to white Southerners in the Confederacy. The supposition that secession was the product of a few plantation-owning elite families while the average Southerner remained loyal proved to be entirely false.

The only major exception to this would be in the area that would become West Virginia, and in other Appalachian regions to a degree. When Union armies occupied central Tennessee and Northern Virginia early in the war, they expected to be joined by loyal locals but were instead treated to a hostile response.

Citizens in those areas continued to join the Confederacy and even raided behind Union lines.

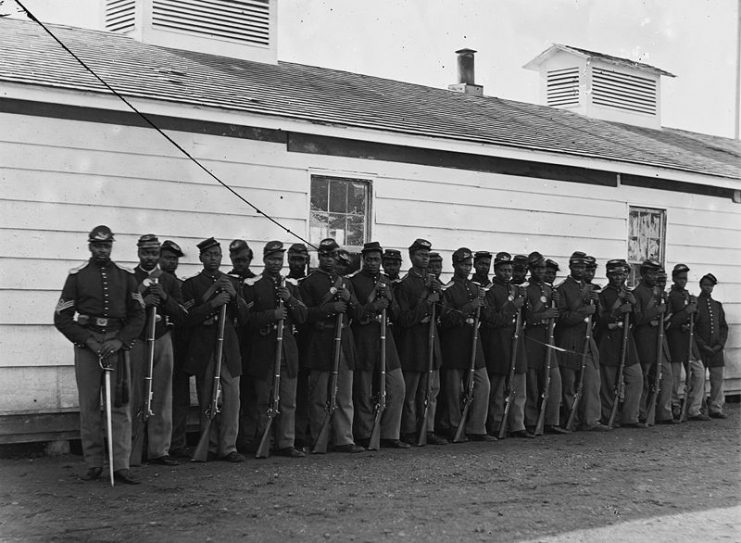

The only major group of Southerners to support the Union was, unsurprisingly, slaves and former slaves. However, even their support was tempered by the decision of many generals early in the war – before the Emancipation Proclamation – to return escaped slaves to their masters since slavery was still legally protected in those states.

Even in the Border States, Lincoln’s strategy was to place Unionists in positions of power in state legislatures, rather than counting on winning over the average citizen.

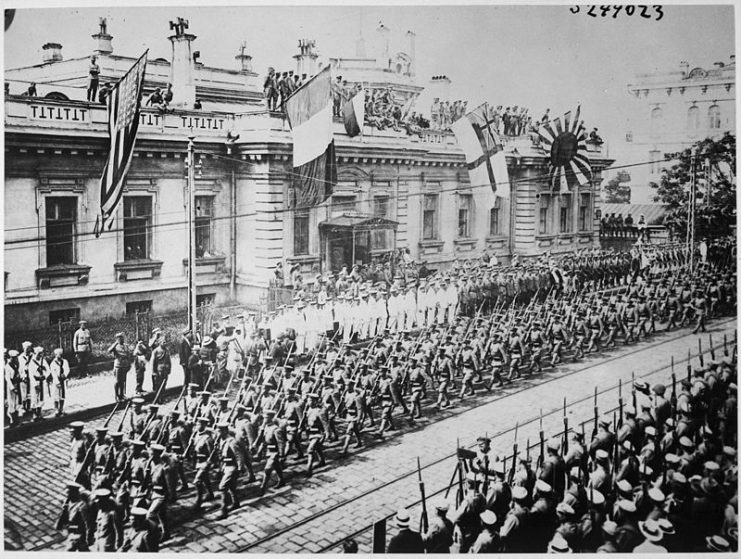

The “Polar Bear” Expedition

The Polar Bear Expedition was a little-known American intervention in the Russian Civil War. Ostensibly this intervention was designed to bring Russia back into the war by removing the Bolshevik government and saving a group of soldiers loyal to the Tsarist government.

At first, the English General, Frederick Poole, supported a more “moderate” anti-Bolshevik Leftist government in Northwestern Russia where the Americans landed.

However, he then decided that he wanted to establish a reactionary monarchist government instead. This decision immediately alienated any Leftist anti-Bolshevik supporters the Allied invasion might have found.

Making matters worse, another British commander remarked that he “saw no purpose for a government here anyway,” and Poole became known for “his colonial approach to Russians,” according to historian Robert Willett. Given this arrogance, condescension, and flip-flopping between anti-Bolshevik factions, it is no surprise that the Allied forces found little local support.

Even when individual soldiers gained the respect of locals, incompetence from their commanders soon erased all progress. On one occasion, Allied forces torched part of a village in retaliation for sniper attacks. By the end, they had lost what support greeted them upon their arrival.

Vietnam

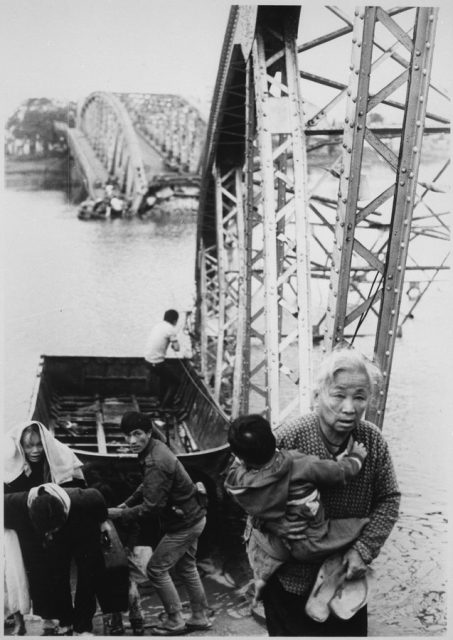

The most (in)famous use of a “hearts and minds” campaign by the United States came during Vietnam, and it failed as utterly as any other. Crucial factors were the disorganized nature of the war, local support for the Viet-Cong, and the difficulty in telling apart friend and foe.

President Lyndon Johnson declared that “ultimate victory will depend upon the hearts and the minds of the people who actually live out there.”

The strategy involved providing security to villages, expanding access to services like electricity, and a propaganda campaign showing the Viet-Cong as merciless aggressors. However, the idea of providing security and denouncing the Viet-Cong was undermined by the behavior of American command, which often resorted to using extreme firepower to put down resistance.

Historian and author, George Herring, notes that “American firepower destroyed homes, villages, and crops, and alienated those whose hearts and minds were to be won.

American commanders declared entire areas free-fire zones. Troops would round up villagers, burn their hooches and relocate them from their ancestral lands into squalid refugee camps.” Unsurprisingly, hearts and minds were not won.

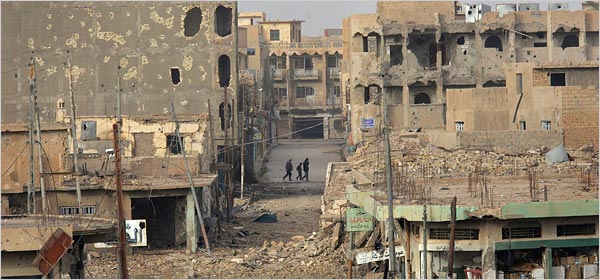

Iraq

The latest example of a largely failed hearts and minds campaign is the ongoing war in Iraq. During testimony before Congress in the lead up to the wars, several absurd claims were made. These included that Iraqis would readily accept US occupation, and that they would come forth with candies, kites, boom boxes, and smiles to greet the American liberators.

In reality, a massive insurgency erupted because, as Samer Shehata succinctly explained, “One of the many problems with such naively optimistic predictions is that they failed to recognize that Iraqis, while welcoming the end of Saddam’s regime, simultaneously disdained the idea of foreign troops in their country.”

As the United States pursued plans to rebuild or expand infrastructure in a bid to win over civilians, distrust in the occupying forces increased due to the growing length of the occupation. By 2005, when asked if Americans were “occupiers” or “liberators,” 71% of Iraqis answered occupiers.

Soon, many began to question the motivation of the occupation, and old sectarian divides started to reemerge under the newly installed democracy.

Even American efforts to rebuild infrastructure fell flat, as it often took years to repair the damage, and corruption was common. Ultimately, the attempt to win hearts and minds in Iraq ended up a complete failure.

So what can the American government learn from these failures?

It is clear that any good-will generated from removing the previous regime does not last long. Consequently, the possibility of winning hearts and minds in any extended conflict should not be taken seriously. When it comes to operations like expanding infrastructure and education, Americans also seem to significantly overestimate their abilities in this area.

In reality, due to insufficient funding, poor planning, and corruption in the organizations responsible for carrying out these plans, such efforts have never truly been successful. Americans need to realize that they can be seen as an oppressor by native populations just as easily as the regimes they are replacing.