I began colourising black and white photos professionally in 2014, coinciding with the centenary of the outbreak of WW1 in 1914. Around the world there was a renewed interest in a war that had not been fresh in the public memory for many years.

Since 2014, I have been very fortunate to have been able to work with some high profile clients around the world on exhibitions, press articles and books commemorating significant WW1 anniversaries. And I have also been honored to work on clients’ personal family photos, which all have unique insights into what was truly the first global conflict.

To mark the centenary of the end of the First World War, I have decided to collate 100 images I’ve colorized in tribute to the men and women who lived through the war, and those who lost their lives.

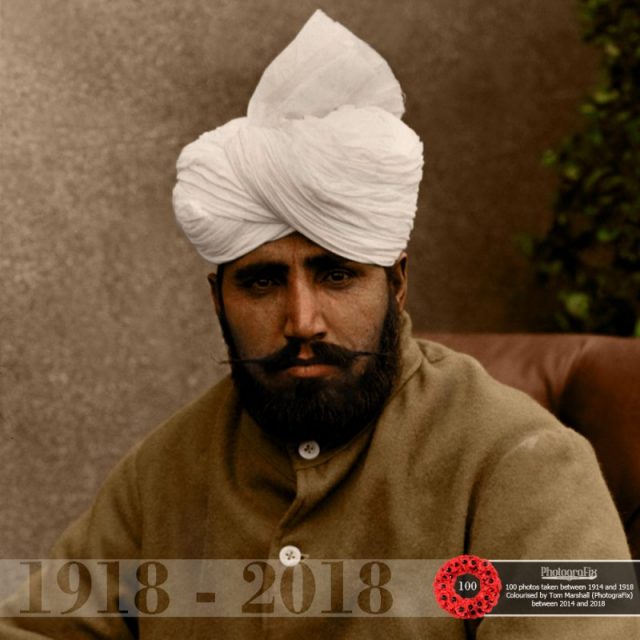

I have chosen to include men and women of several nationalities, races and religions, as the entire world was affected by the war, and I hope the photos will show an insight into the lesser known stories and events.

Some of the images you may be familiar with, but many have never been published before.

I have tried where possible to give credit to the original photographers, and the owners/custodians of the original photographs. Where no credit is given, this is due to a lack of information and I would be happy to amend details if they come to light in future.

My thanks goes to the Facebook page WW1 Colourised Photos, a group of fellow friends and colorizers have provided me with helpful advice. It’s impossible to know everything, as hard as I try!

I would especially like to thank my loyal clients and friends who have given me permission to include their personal family photos in this collection as they are by far the most touching images, and they are the most satisfying to ‘bring to life’ in color.

All colorized images are © Tom Marshall (PhotograFix) 2014-2018. Original image credits are given after each photo.

Please consider making a donation to the Royal British Legion’s Poppy Appeal, or to a local memorial appeal in your home country.

Lest we forget.

A man, possibly an official French war photographer is shown behind them, holding a camera and tripod. The derogatory term for a German, ‘Boche’ or ‘Bosch’, originates from the French slang ‘alboche’, which was two words ‘Allemand’ (German) and ‘caboche’ (pate, head) put together. Original image courtesy of the National Library of Scotland.

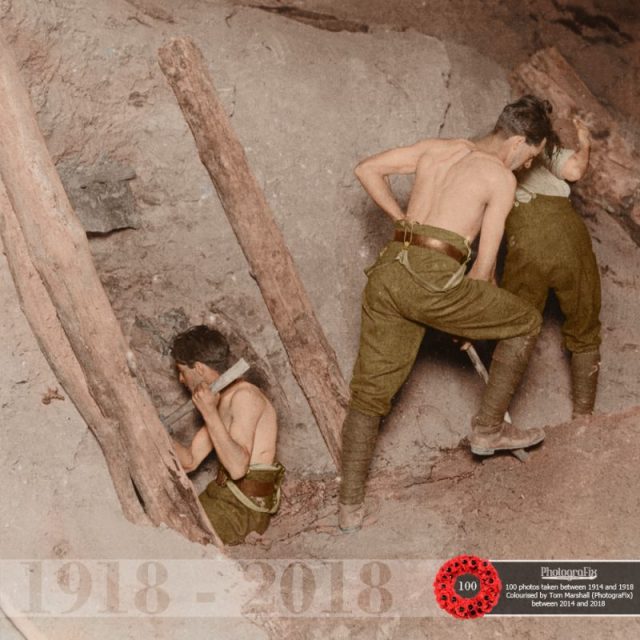

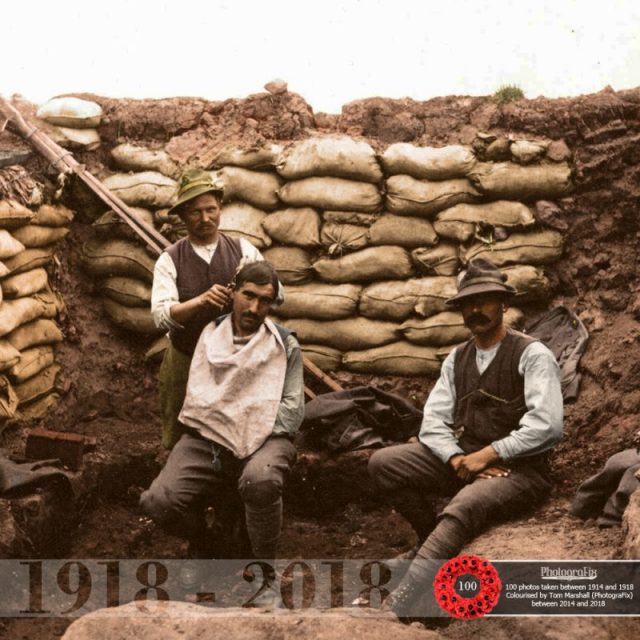

The image comes from an album donated to the National Museum of Ireland by Dr. Horne’s two daughters, Patricia and Margaret. Taking personal photographs at the time was technically difficult and also illegal, unless taken by officers. Dr. Horne went on to survive Gallipoli and the War. He later wrote “Nobody can believe we had such a time and came through it alive, but here we are”. Original image © The National Museum of Ireland.

On 31st January 1916 nine airships, including L20, left Germany and Denmark in order to attack the docks at Liverpool, which would have shocked the British public due to the long range of the attack.

The airships never reached Liverpool and, due to a miscalculation, instead dropped their bombs on several towns including Tipton, Wednesbury, Walsall, Burton upon Trent, Nottingham, Derby, and Loughborough. L20 killed an estimated 10 people in Loughborough including Mary Anne Page and two of her children, whose names can be seen on a plaque in Loughborough Carillon Tower & War Memorial Museum.

On 2nd May 1916, L20 began its second bombing raid on Britain with the intention of attacking factories and railways in Middlesbrough, Stockton-on-Tees and Hartlepool, and targeting enemy warships near Edinburgh. However, engine problems and strong winds led the airship to veer off course.

High winds blew her out into the North Sea and to neutral Norway where she crash landed into Hafrsfjord near Stavanger, Norway. Original image by Hans Henriksen / Stavanger City Archive.

His son Peter Francis Langran served with the same regiment during the Second World War. Thanks to Richard Langran, the grandson of AJ Langran, and son of Peter, who gave me permission to include this photo.

In 1912, he went to Toronto, Canada, where he became the captain of the Devonian Football Club in the Toronto District Football League. When war broke out Ernest enlisted with the 19th Battalion, Canadian Expeditionary Force.

He fought with the Canadian Corps at the battles of the Somme and Arras and was twice-wounded in trench warfare. Thank you to Ernest’s grandson, G.E. Benton for permission to include this photo.

Albert attended Reading University College from 1912-1915 where he took intermediate science and graduated with BSc in 1915. After graduating, he signed up to fight in France, and died on his 23rd birthday, on the 27th February 1917.

Original Image courtesy of the University of Reading archives. Included with the kind permission of Chris Smith.

The book takes its name from a WW1 recruitment poster, which promoted the cycle corps for those men whose bad teeth would deem them unfit for general service. The book is published by Uniform Press.

The ASC later became the RASC and was responsible for land, coastal and lake transport, air dispatch, barracks administration. Also the Army Fire Service, staffing headquarters’ units, supply of food, water, fuel and domestic materials such as clothing, furniture and stationery and the supply of technical and military equipment.

Photographed at Vignacourt, France. Original image courtesy of Ross Coulthart, author of ‘The Lost Tommies’ & The Kerry Stokes Collection – Louis & Antoinette Thuillier.

Robert was a keen pigeoner along with his brothers, and was a husband and father of two young daughters. He joined the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) in 1916 during a recruitment drive following the Gallipoli tragedy in 1915.

Robert died in unknown circumstances in France on 3rd May 1917. Thank you to Glenn Poolen for allowing me to include this photo.

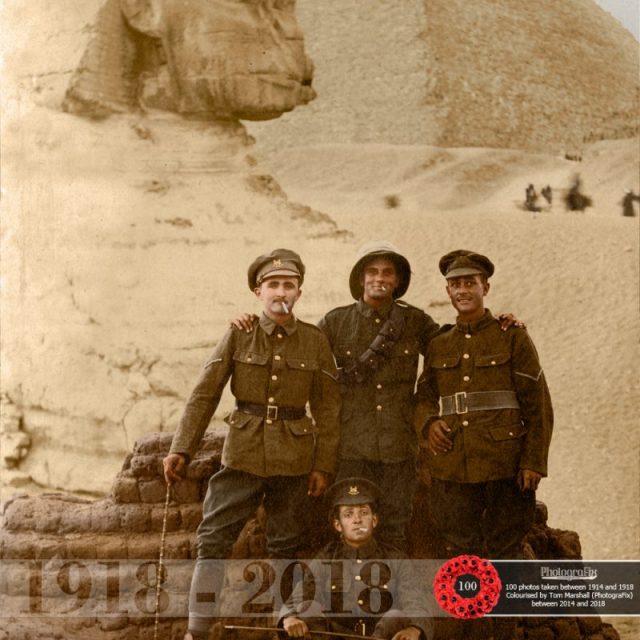

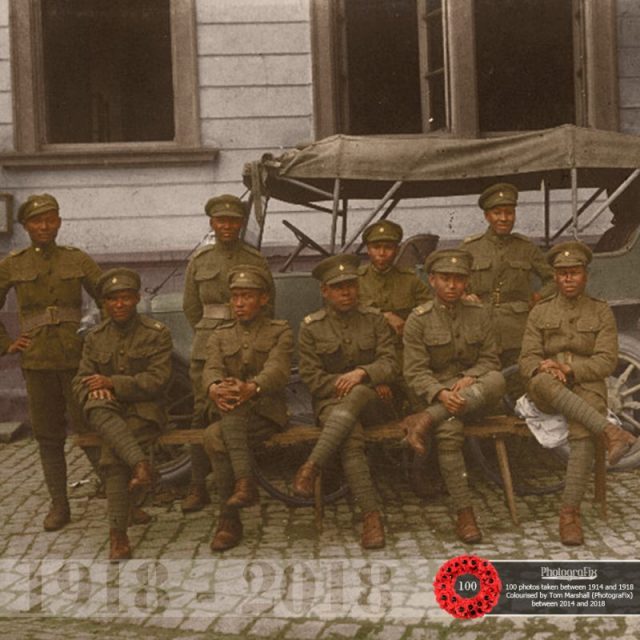

The Kingdom of Siam (now Thailand) is a relatively unknown member of the allied forces during WW1, but after joining the war on the side of Britain and France, Siam sent an Expeditionary Force to France to serve on the Western Front.

Despite the huge amount of damage caused by the bomb, the whole family – mother, father and three children – escaped with their lives. Next door, however, three of the four occupants suffered injury but only one needed hospital treatment.

Thank you to Ian Castle, author of ‘Zeppelin Onslaught’ for the above information. Original photo by H.D. Girdwood, courtesy of the British Library.

Two Zeppelins appeared over East Anglia. Zeppelin L 3 bombed Great Yarmouth and later Zeppelin L 4 appeared over King’s Lynn. This photo is reported to show Mr Fayers who lived at 11 Bentinck Street, King’s Lynn.

A bomb exploded on 12 Bentinck Street, killing 14-year-old Percy Goate. His parents and 4-year-old sister survived. Next door at No. 11, Mr and Mrs Fayers had spent the evening with Alice Gazley who lived nearby.

When they heard explosions, Alice ran out of No. 11 and was killed; although buried in the rubble, Mr and Mrs Fayers sustained only minor injuries, Mr Fayers was ‘cut on head’.

Thank you to Ian Castle, author of ‘Zeppelin Onslaught’ for the above information. Original photo by H.D. Girdwood, courtesy of the British Library.

The path is inches deep in wet mud discernible by the deep imprint round the soldiers boot and the fact that the horses hooves are no longer visible. Rather than cloth puttees though he is wearing long lace-up boots.

The horse is absolutely laden with rubber trench waders. Horses, due to their reliability and ability to travel over most terrains were crucial to transportation during WW1. Original image courtesy of the National Library of Scotland.

The bomb landed in the back garden of 41 Butt Road, the home of Quartermaster-Sergeant Rabjohn of 20th Hussars and his family. Rabjohn, his wife and their child escaped injury.

Thank you to Ian Castle, author of ‘Zeppelin Onslaught’ for the above information. Original photo by H.D. Girdwood, courtesy of the British Library.

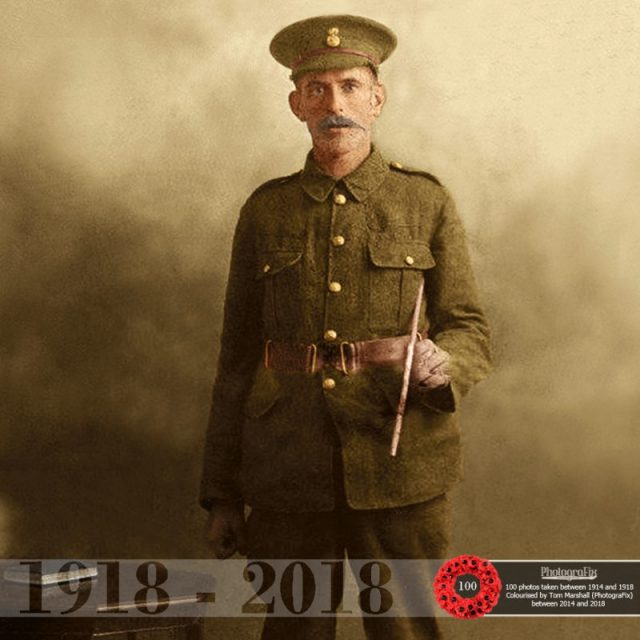

From his cap badge I’ve been able to find out that Frank served with the Loyal North Lancashire Regiment 1914-1918 in the British Army.

Sadly, I also found out that Frank was killed on 28th August 1918, aged 21 and is buried at the Reninghelst New Military Cemerery in Belgium.

He was the son of Joe Lister Sheard and Alice Sheard of 5 Brick Bank, Almondbury, Huddersfield, West Riding of Yorkshire.

From his shoulder badge I’ve worked out that he served with the Lincolnshire Yeomanry, the same as my Great Grandad, and by searching online have found a record for John Arthur Lovell.

Thank you to Ian Castle, author of ‘Zeppelin Onslaught’ for the above information. Original photo by H.D. Girdwood, courtesy of the British Library.

He is sporting the ribbon of the Military Cross and may well have been a well known man, photographed at Vignacourt, France.

Original image courtesy of Ross Coulthart, author of ‘The Lost Tommies’ & The Kerry Stokes Collection – Louis & Antoinette Thuillier.

During WW1 tirailleurs from North African territories served on the Western Front as well as at Gallipoli, incurring heavy losses. Note the “dog tag” on his wrist – two were issued one for the wrist, the other was worn around the neck.

The Great Mosque of Paris was constructed afterwards in honour of the Muslim tirailleurs who had fought for France. This photo is included with the permission of Moucan’s grandson Andre Chissel.

According to the photograph’s original caption these soldiers are the first to have crossed the River Somme. Some of them are clambering up a temporary walkway. Others in the background manage to scramble up the embankment. The foreground is littered with debris.

Scenes such as this were commonly used as propaganda, intended to boost morale amongst the troops. Original image courtesy of the National Library of Scotland.

It seems to have been made of a mixture of corrugated iron, wood and canvas or tar-paper. As it is built above ground, this must have been well away from the front-line trenches.

This is one of a number of photographs which illustrate the degree to which shelter was left to the individual soldier. For officers this was, however, relieved by their greater freedom off-duty to go to nearby towns and villages, or on longer leave to visit Paris.

When billets were available in civilian houses, officers again had the better conditions. Original image courtesy of the National Library of Scotland.

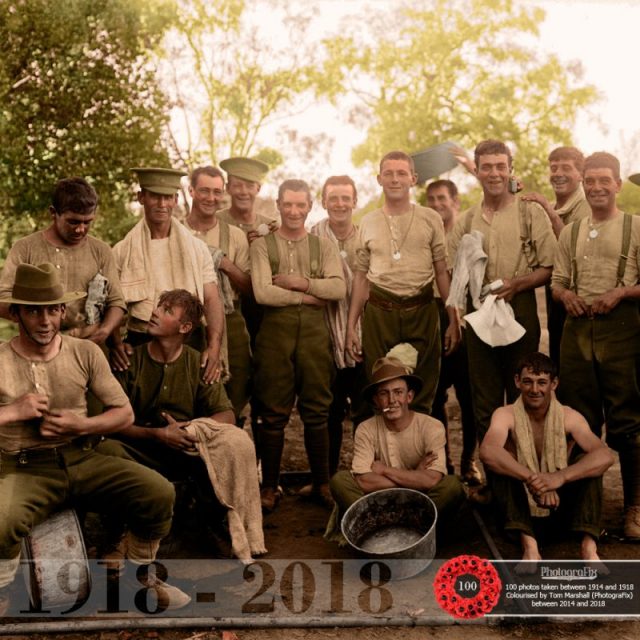

Other men are outside, standing beside a washing line with towels on it. A pot is steaming on a brazier made of a tin drum.

The cap and collar badges of the men are not distinct but appear to vary, suggesting they are from more than one unit. This rather domestic scene appears well removed from the reality of the trenches at the Front.

It may have been intended to counter criticism of the campaign by implying that it was better organised than was the case. Original image courtesy of the National Library of Scotland.

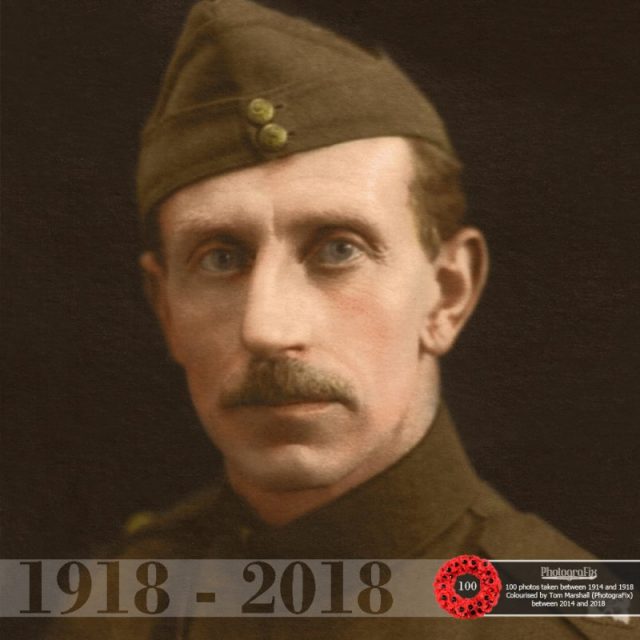

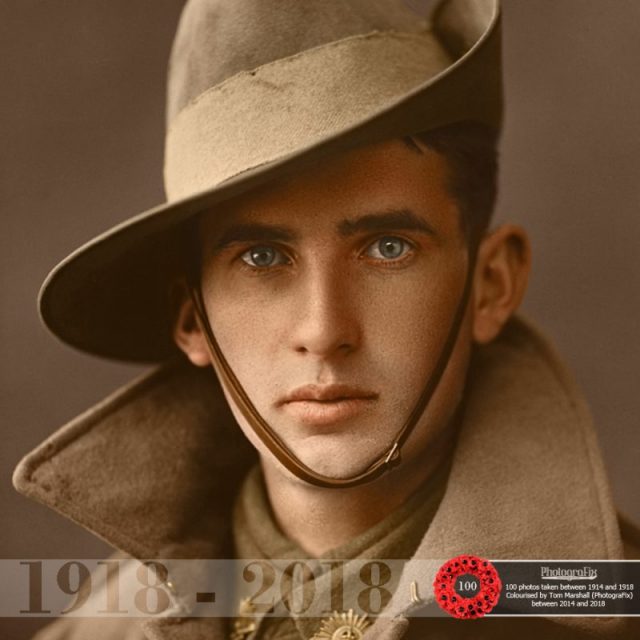

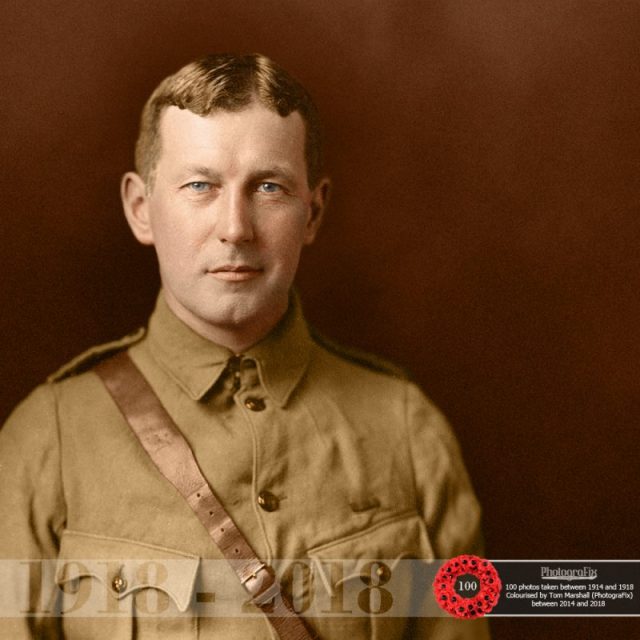

I was drawn to the eyes in this photograph. They look like the eyes of a man who has seen too much. When colourising the images it’s impossible to know the subject’s eye colour from the black & white image.

As his hair is light and fair, blue eyes are a guess, and in turn make the image more striking. Original image courtesy of Ross Coulthart, author of ‘The Lost Tommies’ & The Kerry Stokes Collection – Louis & Antoinette Thuillier.

The other-worldliness of this ravaged landscape at Courcelette, shrouded in clouds of dust or smoke, leaves a lasting impression.

The foreground is littered with many objects, including an abandoned carriage and a sign stating ‘pack transport this way.’ Original image courtesy of the National Library of Scotland.

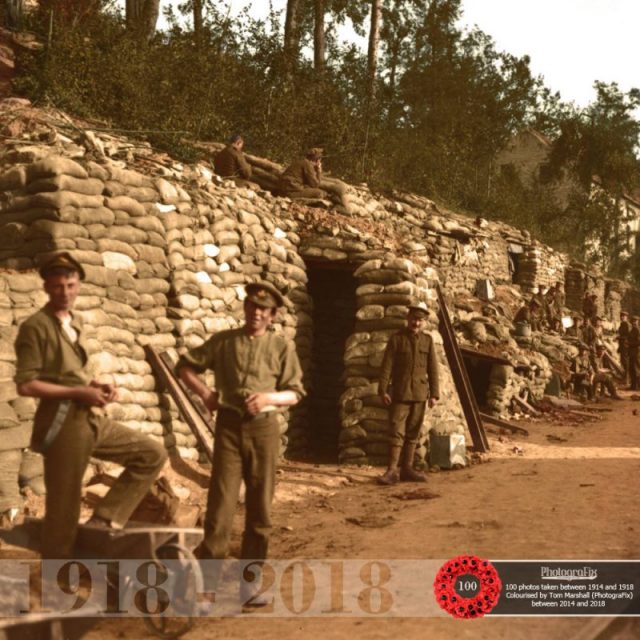

Three officers stand outside the mouth of the trench whilst one sits on top of it and one stands inside it.

They all appear happy or relaxed, presumably as they have just captured a German trench and all the supplies in it. Original image courtesy of the National Library of Scotland.

According to the existing caption it is a controlled explosion set up by the Royal Engineers, to clear the way for the advance. A uniformed soldier, possibly a member of the Royal Engineers, sits on a wooden post watching the explosion.

A retreating army often laid obstacles and sabotaged any equipment or weapons they left behind, in an attempt to hinder any advance.

Royal Engineers, as well as taking part in the fighting, were also responsible for ‘combat engineering’; finding solutions to engineering problems on the battlefield. Original image courtesy of the National Library of Scotland.

A group of men from the Royal Regiment of Artillery, photographed alongside a long-barreled field gun, 1916. For the occasion, they have chalked the words, ‘Somme gun’ on the side of the barrel.

The men are well wrapped with non-uniform scarves, gloves and a balaclava. In purely military terms, the heavy artillery of both sides was in many ways more important than any other weapon.

It could fire into the opposing trenches with little risk to their own side and could effectively keep the enemy in the trenches. Original image courtesy of the National Library of Scotland.

He served in the South African Constabulary as a 3rd Class Trooper between 1901 and 1903, fighting in the Boer War for which he was awarded the Queen’s South Africa Medal.

When WW1 broke, having emigrated to Canada, Forrest enlisted in Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry and in December 1914 embarked with the Canadian Expeditionary Force to France, where he fought in the frontline trenches, and was promoted to Sergeant.

After being granted a commission to the British Army, Forrest spent 1916 serving in Northern Egypt, and in August 1916, he transferred to the Royal Flying Corps as a Flying Officer (Observer) attached to 14 Squadron, 5th Wing.

He performed reconnaissance in the Hejaz region of Western Arabia in support of Lawrence of Arabia during the early stages of the Arab Revolt.

In May 1917, having been promoted to Lieutenant and attached to 57 Reserve Squadron, 20th Reserve Wing, Forrest took part in a Special Duty Service Flight performing reconnaissance in the Northern Sinai region of Egypt.

For the remainder of 1917, he was Recording Officer for 111 Squadron, 5th (later 40th) Wing, stationed in the Suez. Returning to Britain in December 1917, Forrest was attached to Home Defence Wing, initially in 39 Squadron whose duties were to intercept Zeppelin bombers attacking London.

He was subsequently attached to 189 Night Training Squadron and then 153 Squadron shortly before relinquishing his commission in January 1919.

For his services during World War 1 Lieutenant Forrest was awarded the 1914-15 Star, British War Medal, and Victory Medal.

Thank you to Guy’s Great Grandson Giles Forrest for permission to include his photograph and story here.

The army commander to his right is pointing into the distance and, according to the original caption, recounting the capture of Thiepval.

This photograph was taken by John Warwick Brooke during one of the King’s many visits to the Western Front. The village of Thiepval was completely destroyed during the Somme Offensive of 1916.

A memorial to the missing of the Somme, with no known grave, now stands near where Thiepval Chateau once stood. Original image courtesy of the National Library of Scotland.

Identified, left of the gun, left to right: Gunner (Gnr) W E Drummond Gnr J Brannon (to Drummond’s right) Gnr C V Cox (in front of Brannon) two men unidentified behind Cox 34401 Gnr A Hewitt (in front of Cox) Dvr A C Sampson (standing on wheel, back to camera) Gnr G G Dowling (foreground, pulling rope on front wheel).

Right side of gun, left to right: Dvr Hughes Dvr F Peace unidentified unidentified Bombardier T (R ?) Garniss Sergeant W Reynolds (extreme right, standing back).

Istvan was chosen to be a bodyguard as he was the strongest man in his county. Throughout the Great War he served in the 69th Imperial and Royal Infantry Regiment.

During his service on the Eastern Front, Istvan fell ill for a short period but returned successfully to his farms in Hungary and to his two sons.

This photo was taken in 1918 and shows him wearing his Charles cross medal. Thank you to Istvan’s Great Grandson Peter Kovacs for allowing me to include his photo and story here.

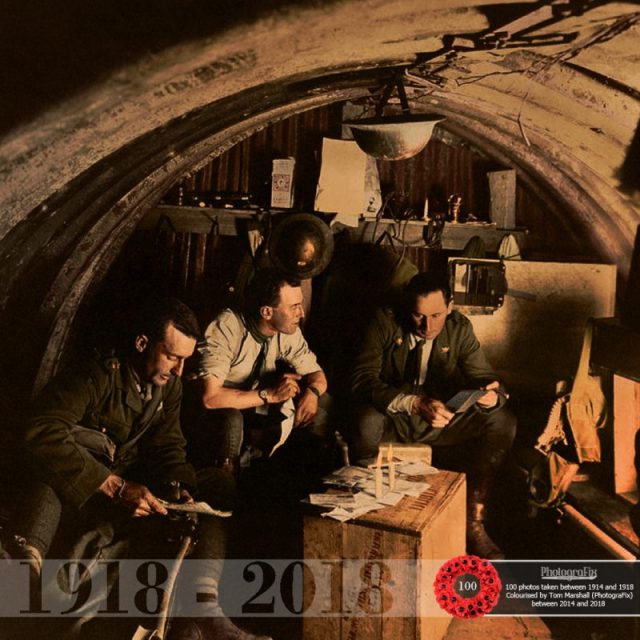

Three officers making themselves comfortable, during the Battle of the Somme, 1916. Steel helmets had many more uses than the War Office might have intended. Original image courtesy of the National Library of Scotland.

A YMCA NZ stall just behind the lines allowed the men to get something to drink. Original image courtesy of the National Library of Scotland.

At the outbreak of the First World War, Colebourn returned to England as a veterinarian and soldier with the Royal Canadian Army Veterinary Corps.

As he was heading across Canada by train to embark for England, Colebourn came across a hunter in White River, Ontario who had a female black bear cub for sale, having killed the cub’s mother.

Colebourn purchased the cub for $20, named her “Winnie” after his adopted home town, and took her across the Atlantic with him to Salisbury Plain where she became the unofficial mascot of the CAVC.

When Colebourn shipped out to France, he kept Winnie the bear at London Zoo. It was at London Zoo that the author A. A. Milne and his son Christopher Robin encountered Winnie. Christopher was so taken with her that he named his teddy bear after her, which became the inspiration for Milne’s fictional character in the books Winnie-the-Pooh (1926) and The House at Pooh Corner (1928).

Left to right: Captain Leslie Russell Blake MC Polar Medal (died of wounds on 3rd October 1918); Lieutenant David Ballantyne Ikin; Major Herbert Norman Morris, Officer Commanding.

Australian photographer and adventurer Frank Hurley was a master of light and shadow. He participated in a number of expeditions to Antarctica and served as an official photographer with Australian forces during both world wars.

In WW1 Kálmán served in the Royal Hungarian Hussars and on the 1st November 1915 was promoted to the rank of Főhadnagy (Lieutenant).

He was awarded the Bronze Medal for Bravery and Karl Troop Cross, in 1917 & 1918 respectively serving in the Serbian Campaign. Thank you to Kalman’s grandson Andrew Gerencser for permission to include the photo here.

The photograph was taken on the 13th May 1918 by Henry Armytage Sanders. The sign above the entrance reads; “The Diggers rest. Board and residence. Cold showers when it is wet. Herr Fritz’s Orchestra plays at frequent intervals.”

And a Good Conduct (Three Years) chevron on his left sleeve, photographed at Vignacourt, France. Original image courtesy of Ross Coulthart, author of ‘The Lost Tommies’ & The Kerry Stokes Collection – Louis & Antoinette Thuillier.

He is wearing the Military Cross medal ribbon, but I have not been able to work out the other ribbons.

Based on his age, rank and the shades of grey, I have painted these as Boer War campaign medals, though this is merely speculation as I don’t know his identity.

Original image courtesy of Ross Coulthart, author of ‘The Lost Tommies’ & The Kerry Stokes Collection – Louis & Antoinette Thuillier.

He was inspired to write “In Flanders Fields” on the 3rd of May, 1915, after presiding over the funeral of friend and fellow soldier Alexis Helmer, who died in the Second Battle of Ypres.

Its reference to poppies that grew over the graves of fallen soldiers led to the rise of remembrance poppies issued by the Royal British Legion, the Royal Canadian Legion, the American Legion Auxiliary and other associations around the world. Lest we forget.

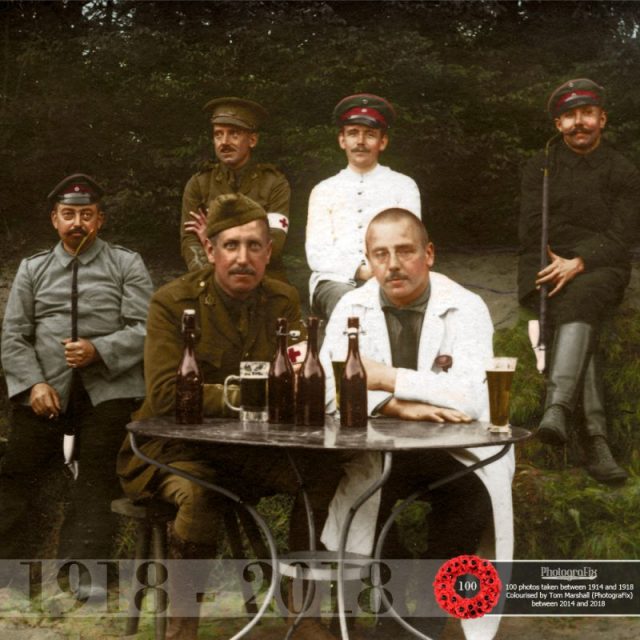

This is most likely a staged propaganda photograph, although reports do show that officers were treated better than enlisted men.

According to one prisoner’s account of Sennelager camp in September 1914, “it was an open field enclosed with wire… there were no tents or coverings in it of any kind. There were about 2,000 prisoners in it – all British.

We lay on the ground with only one blanket for three men.” Seated at the left of the table is Major William Egan DSO OBE, of the Royal Army Medical Corps. The above info is thanks to his granddaughter Patricia Harty, editor-in chief of the Irish America Magazine. Original image © The National Museum of Ireland.

Pictured are two different nursing organisations, the Territorial Force Nursing Service (TFNS) and the Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service (QAIMNS).

The TFNS wore a blue grey cape with a scarlet trim, and just visible on the uniforms of the nurses to the left of the image is a small silver ‘T’ which defines them as such.

The nurses to the right of the picture are QAIMNS with scarlet cuff bands and a scarlet cape. They are wearing the QAIMNS cape badge (or medal) (which differentiates her from the QAIMNS Reserve who had a different type of badge.)

The badge or medal was part of the uniform and was to be worn at all times. The two scarlet bands on the cuff show them to be a nursing sisters rather than matrons. Original image © The National Museum of Ireland.

Charles Martin King is dressed in a fusilier uniform, and later went on to join the Royal Flying Corps and was promoted to 2nd Lt. In the RAF in April 1920.

In the Second World War he was given a chaplaincy in the Royal Army Chaplains’ Dept on 6th November 1943 and was one of the first to enter Bergen Belsen prison camp after liberation.

Maurice (seated) was a Private 528 in the 33rd Battalion, B Company of the First Australian Imperial Force, (marked by the small green & black disk on his shoulder).

His unit embarked from Sydney, new South Wales on 4th May 1916 with the intention of heading to Egypt, but en route they were directed (via Durban, Cape Town and Dakar) to England, arriving on 9th July 1916.

As this photo is dated 1916, and was taken in the village of Long Buckby, Northamptonshire, it leads me to believe that this photo was taken that summer when the brothers had a brief chance to meet up (during Maurice’s training period), before his battalion went on to fight in France in November 1916.

Charles would go on to be awarded the medals Croix de Guerre and Croix du Combattant and was called up again in WW2 aged 45 in the pay corps.

The lanyard or “fourragere” is in the colour of the Legion of Honour – In order to receive such a lanyard, a Regiment had to receive six unit citations and only 11 French Regiments received six unit citations during the war.

This photo is included with the permission of Moucan’s grandson Andre Chissel.

Prior to the war Alfred had served with the British Red Cross Society during the First Balkan War in 1913. During WW1 he served 1 year with the 5th Sutherland Highland Rifle Volunteers in France and Flanders, obtained a commission and was promoted to Lieut.

Special Lists (Interpreter) in July 1917. Alfred married Marion Sutherland on 3rd May 1917 and they had a daughter, Margaret on 11th February 1918. In 1918 Alfred was attached as interpreter to the South Persian Rifles where he was promoted to captain and awarded the Military Cross.

He was killed in an uprising on 25th May 1918. The medal ribbon shown in the photo is his Red Cross Medal. Thanks to Alfred’s Great Great Nephew Alasdair Will for his story and permission to include the photo here.

The Siamese saw front line action in the middle of September 1918, shortly before the end of the war. When this photo was taken, Siamese troops were contributing to the occupation of the Rhineland, and took over control of the town of Neustadt.

Original images kindly provided from the old collections of Geinsheim families by Norbert Kästel of Geinsheim Heimatverein.

Thank you to Stephen Martin who commissioned the colourised version for the upcoming book ‘Soldiers of Siam’ by Khwan Phusrisom and Stephen Martin, being published by Silkworm Books.

More than 1.6 million women took on traditionally male jobs during the war as male workers flooded into recruiting offices and were shipped to the front line in France.

950,000 women worked in dangerous munitions factories such as this, producing 80% of the UK’s armaments and were known as ‘Munitionettes’ or canaries, due to the yellowing effects that working with sulphur had on the skin.

Poor working conditions and inadequate safety equipment resulted in around 400 deaths, including an incident in January 1917 when 73 people were killed by an explosion in a London munitions factory that also flattened 900 surrounding homes.

The ship sank off the coast of Ireland, killing approximately 1,200 people, including 94 children. The sinking of the ‘Lusi’, one of the largest, fastest and most luxurious passenger liners of its day, caused widespread shock and outrage.

The anti-German sentiment it provoked was used as a recruitment tool in the British war effort and helped to shift public opinion in the United States against Germany, leading them to enter the war in 1917.

The German government claimed that Lusitania was a legitimate target due to the war supplies she was carrying – as were many other British ships. However, British and American enquiries later declared the sinking to have been unlawful.

The colour scheme shown was from an earlier voyage as reports suggest that on her fateful voyage, the funnels had been painted black as a form of wartime camouflage.

They were sweethearts who later married and became farmers in New Brunswick, Canada and Down East Maine. Thank you to Diana Haynes for permission to include the photo here.

The crash, which involved five trains, killed a probable 226 and injured 246 and remains the worst rail crash in British history in terms of loss of life.

Those killed were mainly Territorial soldiers from the 1/7th (Leith) Battalion, the Royal Scots heading for Gallipoli. The precise death toll was never established with confidence as the roll list of the regiment was destroyed by the fire.

The crash occurred when a troop train travelling from Larbert, Stirlingshire to Liverpool, Lancashire collided with a local passenger train that had been shunted on to the main line, to then be hit by an express train to Glasgow which crashed into the wreckage a minute later.

Gas from the lighting system of the old wooden carriages of the troop train ignited, starting a fire which soon engulfed the three passenger trains and also two goods trains standing on nearby passing loops.

The Battle of Guillemont was part of the Battle of the Somme, the largest battle of the First World War, with over 1,000,000 men wounded or killed over both sides.

German writer and philosopher Ernst Jünger’s account of Guillemont in his memoir ‘Storm of Steel’, may well sum up how many were feeling at the time. “All was swathed in black smoke, which was in the ominous under lighting of coloured flares.

Because of racking pains in our heads and ears, communication was possible only by odd, shouted words… When day dawned we were astonished to see, by degrees, what a sight surrounded us.”

Original photo © The Welsh Guards Archives, colourised for the book ‘Bearskins, Bayonets and Body Armour’.

Sidney was also an unknown soldier for 100 years, until the BBC’s The One Show shared the images and he was identified by his grandson Geoff Spicer.

I was asked to colourise this image by the One Show’s production team. Original image courtesy of Ross Coulthart, author of ‘The Lost Tommies’ & The Kerry Stokes Collection – Louis & Antoinette Thuillier.

All colorized images © Tom Marshall (PhotograFix) 2014-2018.

You can also follow PhotograFix on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

If you managed to get this far, well done and thank you. If you’d like to support my colorizing work, several prints are available to purchase here. Please share this blog post with friends and family, as 90% of my work comes from word of mouth.