In the space of just over a century, fighter aircraft have gone from non-existent to a vital part of modern warfare. Here are 11 key developments in that journey.

Biplanes and Triplanes

At the start of WWI, some of the planes fielded as scouts and then fighters were single-winged planes or monoplanes. Both sides soon discovered those planes lacked the speed, stability, and maneuverability needed to win in the air. Emerging air forces instead used biplanes and even triplanes, the additional wings adding to their lift and maneuverability.

Mounted Guns

The first fight between planes involved two Mexican pilots shooting at each other with pistols in 1913. Early in WWI, pilots, and spotters carried pistols, rifles, and other weapons into the air.

The mounting of guns onto planes, initially on the passenger’s seat, turned them into combat vehicles. There was now a stable place from which to fire. Spotters became gunners.

Interrupter Gears

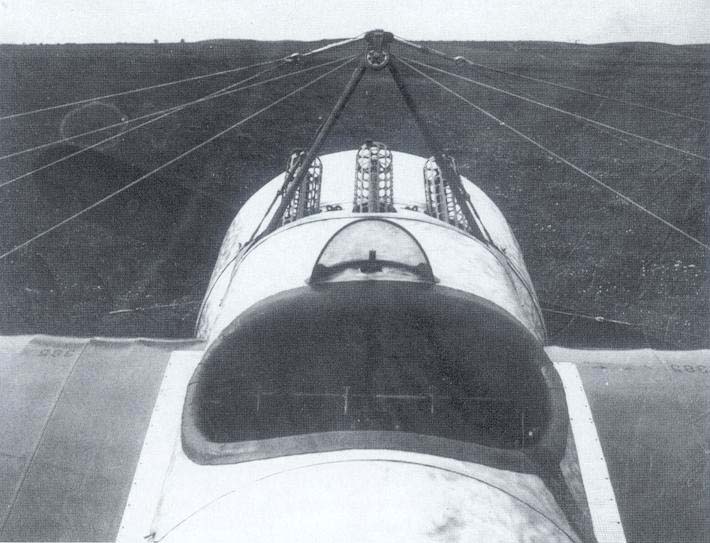

While the gun required to be used separately from piloting the plane, fighters needed a crew of two, between whom coordination could be challenging in the air. The answer was to mount a gun in line with the pilot’s sight so he could aim his weapon by pointing the plane.

The problem was that the propeller got in the way. The solution was the interrupter gear, first perfected by Dutch engineer Anthony Fokker, who mounted it on German planes. It stopped the gun from firing while the propeller was in front of it, allowing it to fire in the gaps in between.

The pilot was now the gunner too.

Back to Monoplanes

The inter-war years saw a growing understanding of aerodynamics and improvements in how to make a plane fly. Developments in design led to a shift back to monoplanes. As the new machines outclassed the biplanes, many air forces still clung to the old technology out of habit and concern that something might go wrong with the new models.

Metal Cladding

The shift toward monoplanes was accompanied by a change in the materials from which planes were made.

WWI planes were made from canvas stretched over wooden frames. The covering made them aerodynamic while keeping them light. It offered no protection to the pilot, who could quite easily have been shot through the canvas of his plane.

More powerful engines allowed engineers to make metal aircraft, which were sturdier both in resisting bullets and in the forces they could withstand as they sped through the skies. Gone were the days when the canvas might rip off a Fokker triplane as it went into a dive.

Cannons

Tougher bodies made fighters harder to shoot down. In the classic pattern of military development, an improvement in defensive technology was swiftly followed by an improvement in offensive technology.

As well as adding extra guns, often mounted in the wings, engineers added cannons. There were a few experiments during WWI, sometimes with unfortunate results. By WWII, many planes were armed with cannon firing explosive shells.

A balance had to be struck, as cannons were slower firing than machine-guns. The top British planes ended up carrying both cannons and machine-guns, to combine quality and quantity.

Electric Reflector Targeting

The 1930s also saw the development of electric reflector targeting. It replaced the crude scopes used since WWI. It provided more sophisticated aiming for more advanced weapons. It also allowed pilots to target their weapons while paying attention to what else was going on around them, an important factor in fast-moving dogfights.

Jet Engines

By the end of WWII, both sides had begun fielding jet planes. With their powerful engines, jets had the potential to seriously outperform their rivals. The very first jet fighter, the Messerschmitt Me262, had a maximum speed of 540mph, 170mph faster than the Supermarine Spitfire, and could climb to 20,000 feet in two-thirds of the time taken by that famous British fighter.

The Me262 arrived too late to make a significant difference in WWII, but it showed the way forward. In the decades following that war, jets became standard, and the first jet versus jet fights took place during the Korean War.

The shapes of planes changed in response to jet engines. With more power, higher speeds, and continuing understanding of aerodynamics, a now familiar swept-back shape became the norm.

Ejector Seats

With higher speeds came greater risks. Just giving fighter pilots parachutes was no longer enough to get them out of a damaged aircraft. The Germans, at the cutting edge of jet technology in the early 1940s, found the solution.

The first compressed air ejector seats were fitted to the Heinkel He219A-0. In January 1942, long before jets would become a battlefield presence, the first life was saved by one. Flugkapitan Otto Schenk lost control of his Heinkel during a test flight and survived after ejecting.

Air-to-Air Missiles

Another experiment later in the war was the air-to-air missile.

Soviet Russia experimented with firing rockets from one plane against another in the late 1930s, but it was in the final years of WWII that they made their presence felt. The Germans, again at the leading edge of rocket technology, deployed planes equipped with 24 rockets which they could fire at enemy bombers in a devastating salvo. They provided an even more destructive weapon than cannons.

Guided Missiles

Early air-to-air missiles had impact fuses, which relied on a direct hit, or timer fuses, which might go off before or after passing their target.

Guided missiles with proximity fuses turned air-to-air missiles into truly deadly weapons. They could zero in using radar or heat-seeking technology. They then exploded close to the plane, enough to do destructive damage.