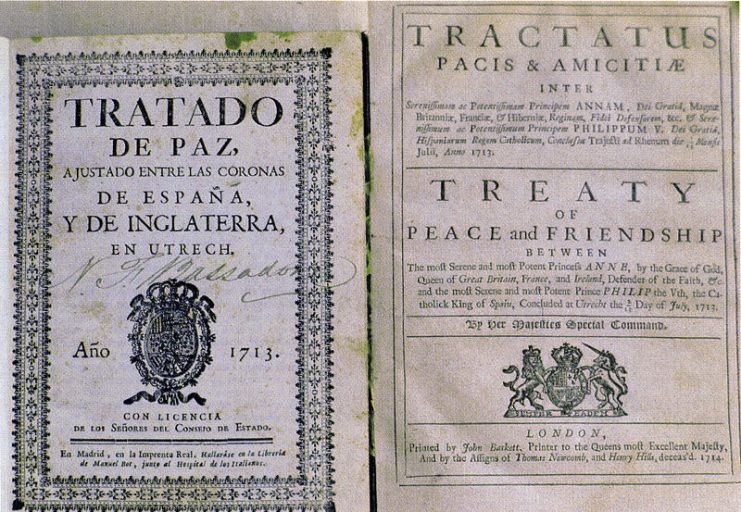

Despite the so-called Peace of Utrecht at the end of the War of the Spanish Succession, Britain and Spain frequently found themselves in conflict between 1713 and 1739.

Master Mariner Robert Jenkins seemed to have a prosperous and secure career ahead of him. The Welshman was engaged in lucrative trade with the Spanish Caribbean, aided by the Asiento contract that the British extracted from Spain after the War of the Spanish Succession.

The Asiento allowed British merchants to trade a limited number of slaves in the Spanish colonies. However, Jenkins’s luck was about to change.

In 1729, the British agreed to grant Spanish warships “visitation” rights on British vessels operating in their waters as a result of the Anglo-Spanish War. Jenkins’s vessel was subject to such a visitation in 1731.

At this point, there are two slightly different versions of events – either the captain himself or one of his lieutenants cut off Jenkins’s ear. Whoever did the deed, what is certain is that Jenkins was separated from his ear by a Spaniard.

The Spaniards told Jenkins to report the event back to his king, and war eventually followed.

Rising Tensions

Despite the so-called Peace of Utrecht at the end of the War of the Spanish Succession, Britain and Spain frequently found themselves in conflict between 1713 and 1739.

These conflicts included the War of the Quadruple Alliance (1718–20) and the Blockade of Porto Bello in 1726 that led into the larger Anglo-Spanish War (1727–1729).

Jenkins’s ear was cut off only two years after the Anglo-Spanish War ended, so it is clear that relations never truly recovered.

It did not help that Spanish captain Juan de León Fandiño allegedly told Jenkins to “Go, and tell your King that I will do the same, if he dares to do the same.”

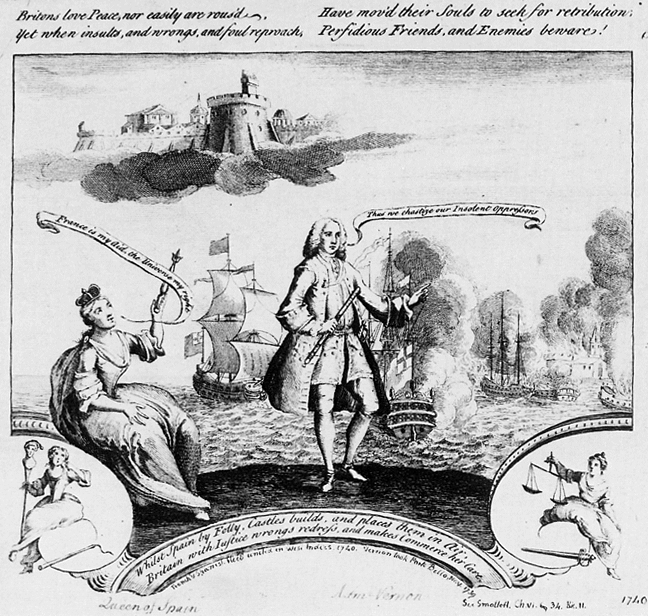

Although a slave-trader is hardly a sympathetic figure by modern standards, the British public at the time was outraged. Many of them felt that they should not stand by and allow one of their countrymen to be maimed by an enemy. It was an insult to their nation as much as to one man.

The Last Chance for Peace

However, neither side was necessarily enthusiastic for war at that time. Both governments sent delegations to El Pardo palace in Madrid to try and de-escalate the situation in 1738.

There, they addressed reparations for the damages to British ships (including the damage to Jenkins’s ear), non-payment of Asiento fees by the British, limits on where the Spanish could search British ships, and a boundary dispute between the Spanish colony of Florida and the British colony of Georgia.

Although the agreement was signed in January 1739, it was unpopular among the British merchants since it compromised on reparations for their losses. Both sides soon violated the treaty, and war seemed inevitable.

Although the popular belief that Jenkins presented his carefully preserved ear before Parliament is probably false, he was called to testify before Parliament in 1738. Regardless of whether the ear was presented, the British public was chomping at the bit for war, and Parliament, in a 257 to 209 vote, obliged.

Parliament sent a formal address to King George II asking him to demand reparations from Spain. On July 20, 1739, Vice Admiral Edward Vernon set sail for the Caribbean to attack Spanish possessions. War was declared in October.

The War Breaks Out

The conflict began poorly for the British, and they suffered from several underlying challenges going into the conflict.

For example, they expected the French to join in on the Spanish side. This would give the Franco-Spanish alliance an overall advantage on the high seas, and made an invasion of the British Isles a real threat.

Therefore, despite the fact that the French never actually entered the war, the British government decided to hold many of its forces in Southern England and refused to launch major assaults in the Americas.

In August 1739, before war was officially declared, Admiral Vernon was ordered to attempt to capture two Spanish treasure ships. The ships’ capture was expected to partially cover the cost of the war.

However, the ships, with their cargo of over seven million British pounds worth of treasure, easily evaded the British fleet.

An early battle went poorly in October when a part of Vernon’s command under Captain Thomas Waterhouse attempted to sneak into the Spanish port of La Guaira disguised as Spanish ships.

The garrison was not fooled and waited for the British to come into range of the shore batteries before opening up simultaneous fire, badly damaging the fleet.

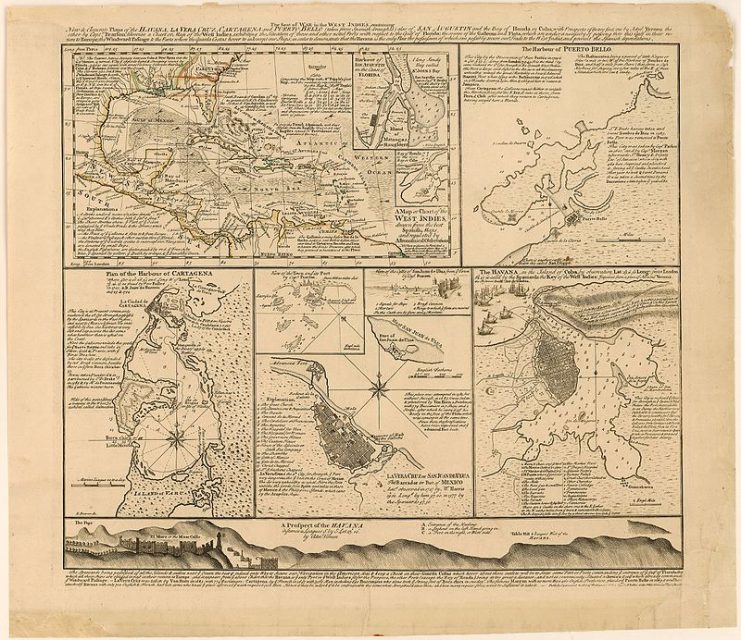

However, British fortunes changed when Vernon launched a successful naval attack against Porto Bello in modern Panama. The silver export hub fell easily, despite widespread doubts that Vernon could take it with only six ships.

Vernon’s men destroyed the town’s major structures, dealing a severe long-term blow to the Spaniards.

Vernon’s victory was widely celebrated in Britain, where the song Rule Britannia was performed in public for the first time at a feast in his honor. George Washington would later name his plantation Mount Vernon after the admiral’s success.

Cartagena de Indias

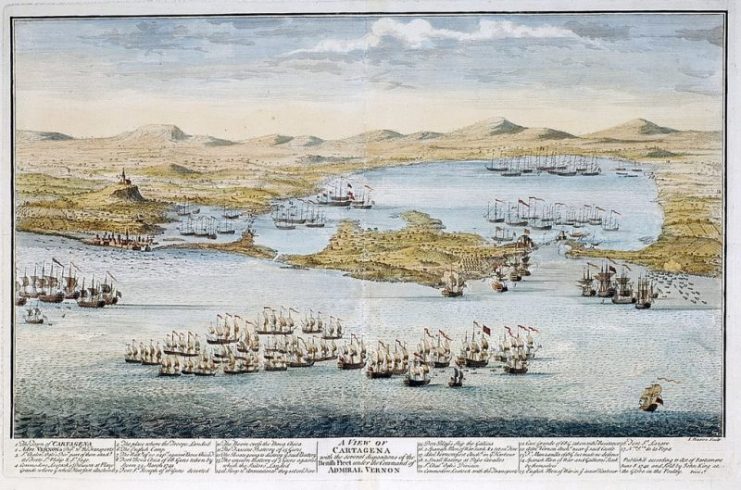

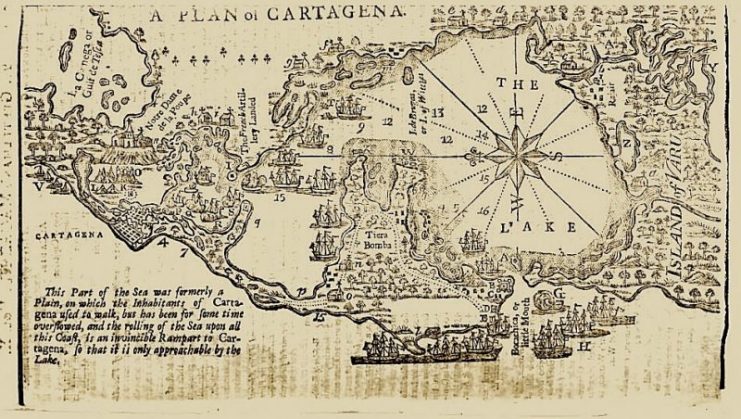

Vernon’s campaign continued with several failed attacks on Cartagena de Indias, the largest trading port in Columbia and one of the largest in Spanish possession. The biggest battle took place between March and May of 1741.

The British force consisted of 186 ships (dwarfing the famed Spanish Armada), 10,000 soldiers, and over 27,000 men in total.

Although Vernon commanded the naval forces, the land forces were commanded by General Thomas Wentworth. Unfortunately for the British, there was a deep rivalry between the two, and they could not cooperate. On the other side stood the legendary Spanish Admiral Blas de Lezo.

The assault on Cartagena de Indias seemed to have a good chance of success at first. De Lezo commanded only around 4,000 men. However, the Spanish fortifications were strong, and British ranks were ravaged by disease throughout the siege.

Although the attackers managed to take several fortifications on the island, the Spanish stronghold at Fort Lazaro still stood in their way. The British assault on the fort would become one of their worst military defeats in the 18th century.

As the Spaniards retreated to consolidate their forces, Vernon encouraged Wentworth to launch a nighttime assault on the fort.

Unfortunately for the British, their only siege engineer had perished in earlier fighting, so they had no way of setting up a proper cannon battery. Consequently, an assault with more primitive siege weapons was necessary.

After landing the previous day, the poorly planned assault on Lazaro began around 4 am.

A group of Americans was in charge of carrying ladders to climb the walls and wool to fill in the trench around the fort. However, the attacking force was misled by a couple of Spanish deserters who claimed to be leading them to a weak point in the walls.

As a result, the British column was greeted with a close-range volley with lethal effect. Most of the unarmed Americans dropped their ladders and ran. However, this did not matter much since the operation was so badly thought out that their ladders were too short for the walls anyway.

As the sun rose, the remaining British soldiers were subjected to cannon bombardment from the fort and the nearby city of Cartagena. When the Spaniards sallied forth, the British had to retreat or risk being cut off.

Ultimately, by the end of the siege, the British had suffered around 18,000 casualties, mostly from disease. The Spanish suffered around two thousand.

Austria and Peace

The British government, which had been told to expect a victory, was shattered by the defeat.

Prime Minister Sir Robert Walpole’s government collapsed, and King George II, feeling his military was too depleted, withdrew his offer to support Austria militarily in their border dispute with Prussia.

As a result, Prussia saw an opportunity to attack Austria, and the War of Jenkins’s Ear became a front in the War of the Austrian Succession.

All powers involved in the war prioritized fighting in Europe, and Spanish America faced little threat for the rest of the war.

The conflict officially ended with the end of the War of the Austrian Succession in 1748. The British lost over 20,000 men and 400 ships for no gain whatsoever. The Spaniards lost over 9,000 men.

In a later treaty, Britain gave up the Asiento in exchange for a payment of £100,000.

Aftermath

So, did nearly 30,000 men really perish because a guy got his ear cut off? Although Jenkins’s loss was a direct cause of the war, it was more of an excuse to settle a pre-existing conflict.

There were also behind-the-scenes domestic reasons for the war in Britain. Robert Walpole, a Whig, was opposed by the Tories and some dissident Whigs. The opposition supported the war and used it as an opportunity to attack Walpole for supposed weakness.

The conflict is remembered more fondly in parts of the United States. Although a minor front in the war, the conflict had significant repercussions for the Georgia colony.

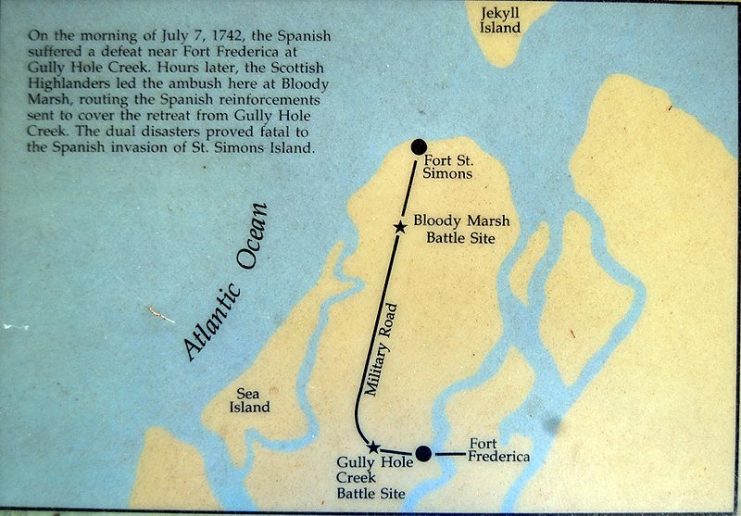

After British assaults on Spanish Florida failed in 1740, the Spanish struck back with a land invasion against Georgia in 1742. Georgia Governor James Oglethorpe rallied local settlers and Native American allies, routing the Spaniards in the battles of Gully Hole Creek and Bloody Marsh.

As a result, the Georgia colony established control over St. Simons Island, which remains part of the state to this day.

Read another story from us: The End of a Catholic Dream: The Jacobite Uprising of 1745

The creation of Oglethorpe’s regiment was the first occasion upon which British colonial troops were made “regulars” in the British army. The war was also the first time colonial troops fought outside of North America, as around 4,000 Virginians took part in the third attack on Cartagena de Indias.

Ultimately, the War of Jenkins’s Ear was a badly botched attempt by the British to seize Spanish lands in the Americas, for which the British paid dearly.