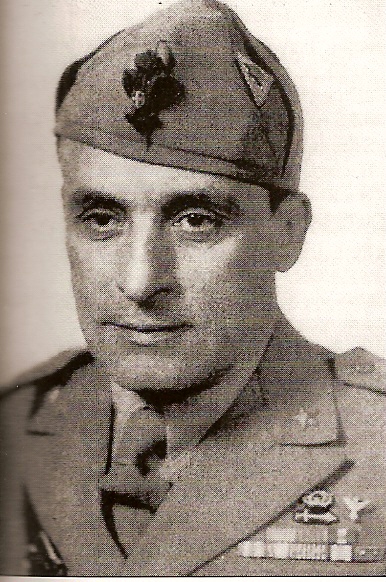

The appointment of Marshal Pietro Badoglio as head of the government after the fall of Mussolini on July 25, 1943, was a disgrace for a country now brought to its knees.

He was authorized to govern the affairs of the state with the sole purpose of ending the war. However, he was mainly concerned with public order. He established police control of the territory, instituted a curfew, and forbade demonstrations and public meetings.

There were arrests, trials, and intimidation. He also imposed censorship of the press.

The peaceful demonstrations for the fall of the dictatorship in Turin, Milan, and Bari were tragically suppressed, further exacerbating the general situation.

He employed the army as part of the police and did not bother to block the borders, a move which would have caused the Germans difficulties in moving their tanks. He did not bother to recall any of the military units in the Balkans, Greece, USSR, and France to the homeland. Instead, he left them without supplies and air support.

He started the procedure for obtaining an armistice with the Allied Nations by arranging for his emissary to meet Allied representatives. The agreement was finalized on September 3, 1943, at Cassibile after long negotiations. Italy requested that less harsh conditions be imposed on it in return for ceasing all war activities.

The Allies required the withdrawal of troops, the transfer of military and merchant ships to a defined base, and the release of all prisoners. These conditions were accepted but General Castellano, an emissary of Badoglio, stated it was impossible to move the ships due to lack of fuel.

Castellano requested the intervention of at least 15 Allied divisions which should be landed north of Rome and north of Rimini. This would split Italy into two sections, with the southern part incorporating Rome in the liberated zone. He also wanted a guarantee that the king and the current government could move to the south of Italy.

General Eisenhower was prepared to authorize the use of an airborne division in defense of Rome against German retaliation at the same time as the mass landing on the peninsula, so long as military control of the two airports around the capital was ensured.

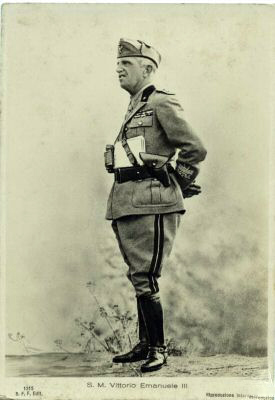

When he returned to Rome, Castellano reported on the results of the mission. He suggested the probable date of the landing would not be before September 12th. However, there was great concern when an Allied radio broadcast about the armistice went out on September 8, 1943. The King, Vittorio Emanuele III di Savoia, and the Council were worried about German reprisals.

The King summoned the Council. He placed responsibility for this dangerous confusion of dates on Badoglio. General Eisenhower’s phone call during the excited meeting worked to stir up the situation even further.

In fact, worried and exasperated by the delay in launching the announcement on the radio by the Italians, Eisenhower said: “To further delay in the observance of the commitments assumed… would follow, consequently, the dissolution of your Government and your Nation.”

But despite being stripped of his responsibilities, Badoglio was later reinstated. After that, he went to the broadcasting headquarters of the EIAR (Ente Italiano per le Audizioni Radiofoniche) to read a message to the nation which had been approved by the King.

“The Italian government, recognizing the impossibility of continuing the unequal struggle against the overwhelming enemy power… asked General Eisenhower for the armistice… the request was accepted… they [the Armed Forces] will react to any attacks from any other source.”

Marshal Badoglio did not specify from whom. He did not order the blockade of borders to avoid German divisions descending on Italy, nor did he declare war on Germany. Badoglio did this only on October 13, 81 days from his appointment and under instructions from Eisenhower.

This is why Italian soldiers who were captured by the Germans were considered traitors and treated as internees not covered by the clauses of the Geneva Convention. He was responsible for the massacres on Kefalonia island (22 September – 390 out of 525 officers) and Cos (on 3 October – 103 out of 148 officers). Badoglio feared the German reprisals that manifested violently against civilians (just to name one: Sant’Anna di Stazzema, Tuscany, 12 August 1944, 560 victims of which 130 were children) and soldiers.

General Maxwell Taylor and Colonel William Gardiner arrived in Rome on September 7 to agree on the arrival of the U.S. Army’s 82nd Airborne Division. They met General Carboni (commander of one of the three Army Corps in defense of the capital). Later in the evening, they met Marshal Badoglio.

He lied and painted the situation in such a dramatic way that he suggested postponing the American intervention and the notification of the armistice. He did not assure the defense of the Rome airports (Furbara, Cerveteri, Guidonia, and Centocelle) because the movements of troops would have alarmed the Germans.

Yet in the Rome area, there were eight divisions: one for the internal defense of the capital (Sassari), four for the perimeter defense (Granatieri, Piacenza, Lupi di Toscana, and Re) and three armored (Ariete, Centauro and Piave) with a Bersaglieri regiment as a maneuvering body.

The two Americans returned to Sicily with nothing.

Despite the adequate defenses in place, the King, the government, and other members of the royal family fearfully fled Rome on the night of the 8th of September. They went to Pescara, where the Navy corvette Baionetta was ready to take them to Brindisi, which had already been freed by the Allied forces.

A film by the director Luigi Comencini, entitled Tutti A Casa, paints a dramatic picture of what was happening in Italy during that dark period. Among other things, the presence of a comedian, Alberto Sordi, among the protagonists makes that terrible story even more tragic.

It represents an Italy divided into two: to the north, the Repubblichini, followers of Mussolini; to the south, the Repubblicani, faithful to the King and the scene of a ruthless civil war. The film shows the living conditions of the already exhausted population, suffering harassment, hunger, and seized by despair for long months.

It also mentions the actions of the partisans who counteracted German activities wherever possible and the violent reactions to the detriment of unarmed civilians. It lingers on the armed forces left without orders and at the mercy of their own destiny while dissolving to the cry of “at home.”

In one scene, the actor Sordi, who plays a lieutenant in command of a platoon, is going to replace another unit. The next moment, he comes under German fire. He then leaves a sergeant in command and rushes to a telephone post to ask his superiors for instructions.

“The Germans are now allied with the Americans. They shoot at us,” he says. He is ordered to reach another command and is abandoned by his soldiers along the way. He remains alone and decides to move away from the front.

After many ups and downs, he arrives in Naples while the population is engaged with “the four days “ struggle against the Germans.

He sees a group of boys in the rubble fumbling with a machine gun. He decides to join them. He picks up the weapon, begins to fire it, and takes part in the fight. Pride and honor find him at last.

Read another story from us: The Italian-Anglo-American Armistice – The Background

In August 2009, at San Mauro Pascoli, in Romagna, a historical process was held with a popular jury to establish Badoglio’s behavior as head of government. The judgment of the almost 300 people present came out as 219 for condemnation and 77 for acquittal.

The verdict took into account the fact that not enough time had passed for those present to reach a judgment that was free from personal resentment but nevertheless established that Marshal Pietro Badoglio was the wrong man, in the wrong place, at the wrong time.