Late in the afternoon of September 17, roughly an hour before the sunset that would mark the close of the bloodiest day in U.S. history, a Maine regiment met with a wholly unnecessary fate.

Just when the regiments’ soldiers thought they’d made it through the battle relatively unscathed, they got pulled back in with disastrous consequences.

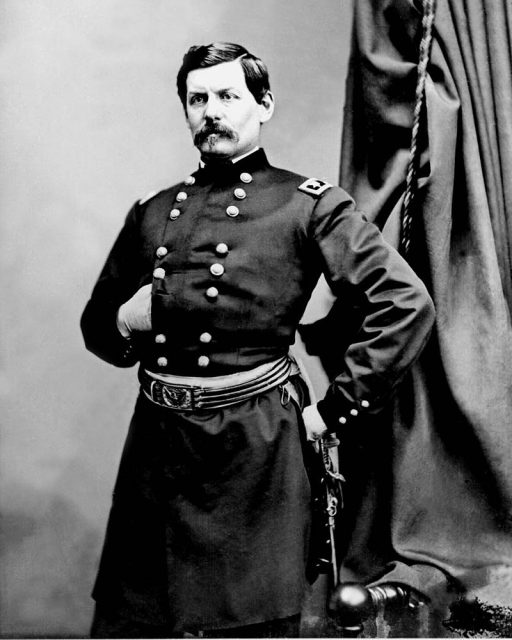

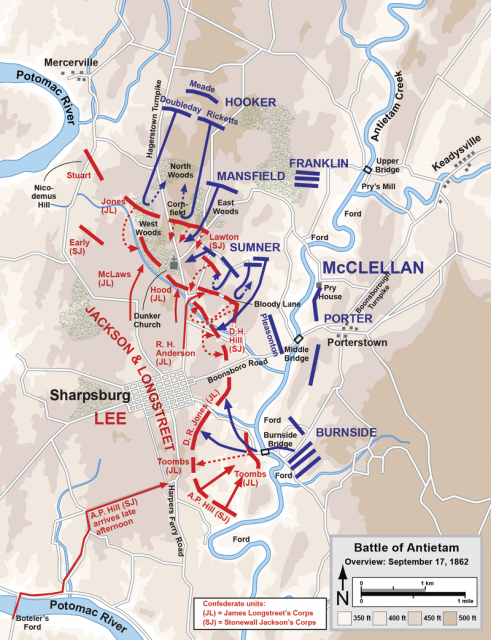

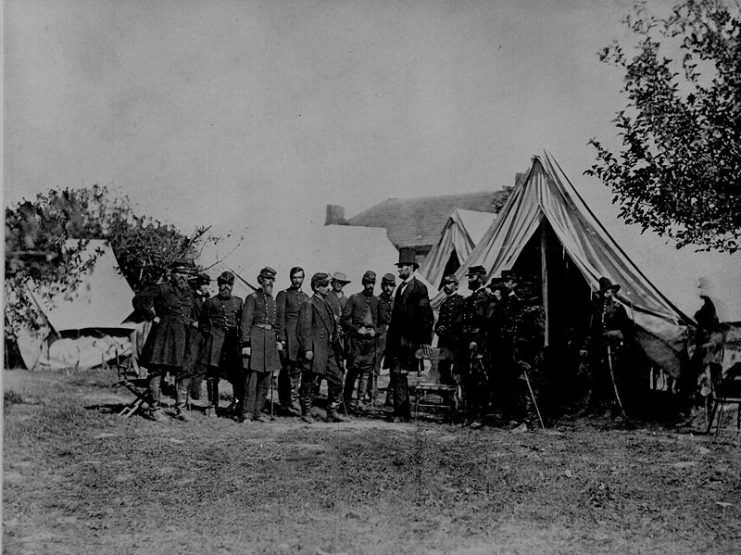

At Antietam, due to Union commander George McClellan’s piecemeal strategy, the fighting was conducted sector by sector. (General Phil Kearny once described McClellan as “fighting by driblets.”) The severe topography of the Antietam Valley, featuring a field carved into discrete sections, contributed further to the situation.

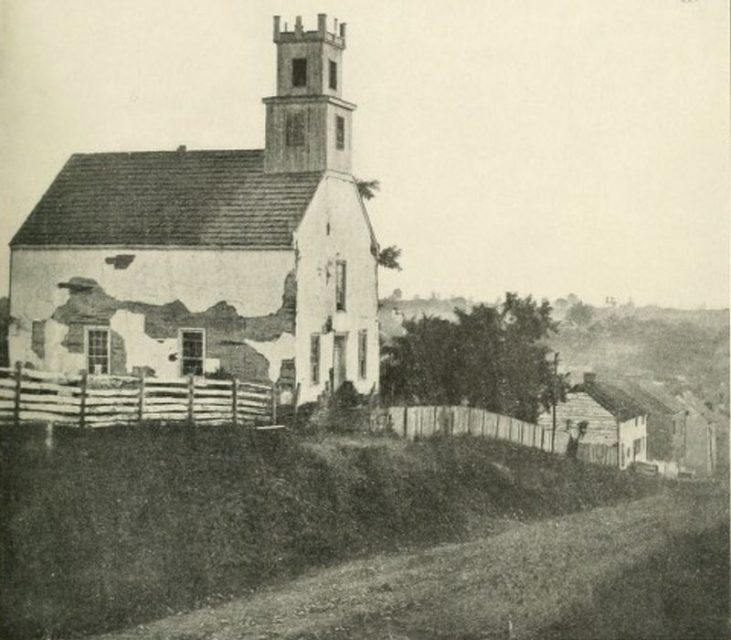

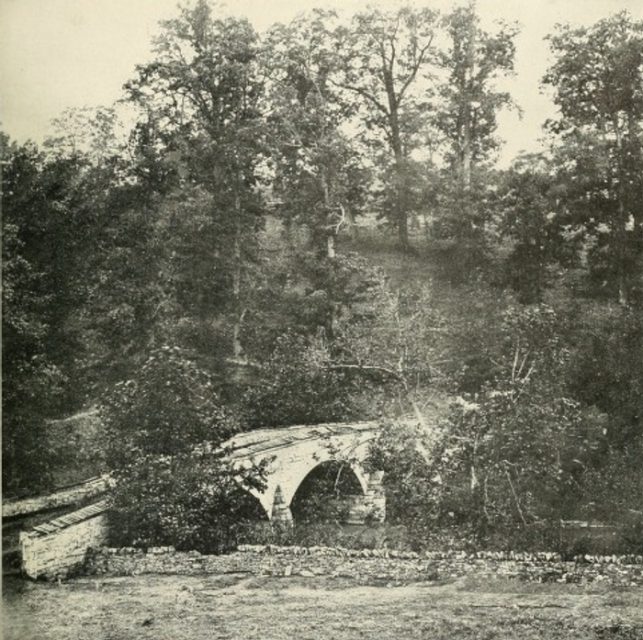

Essentially, the fight shifted over the course of the day, moving from the Cornfield (northern part of the battleground) to the Bloody Lane (center) to the Burnside Bridge (southern section). Although the battle lasted for twelve hours, many soldiers only spent a small portion of that time actively engaged. They fought until the battle died out in their sector, or until their ammo ran out. Then they retreated to safe spots such as a stand of woods, say, or the far side of a hill.

That’s what the men of the 7th Maine believed to be their situation. Back around noon, the regiment had participated in a brief engagement near the Bloody Lane. Afterwards, the soldiers had hunkered down in a choice spot among some boulders, protected from stray shells and shots.

For the past several hours, the Down Easters had been methodically picking off enemy artillerists, and sniping at Rebel officers that wandered into range. They expected that their day was about to come to a close.

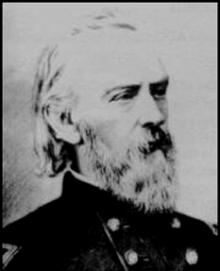

But then—seemingly apropos of nothing—Colonel William Irwin, commander of the brigade that included the 7th Maine, demanded that the regiment storm the Piper Farm. This was a spot where Confederates had retreated after being routed at the Bloody Lane. Just as the Maine boys were whiling away the hours in the relative safety of an outcropping of boulders, many Rebels had sought cover on the farm.

However, this had the potential to be quite a mismatch. The 7th Maine was down to 181 combat-ready men. By contrast, a large number of Confederate soldiers were believed to have fallen back to the Piper Farm.

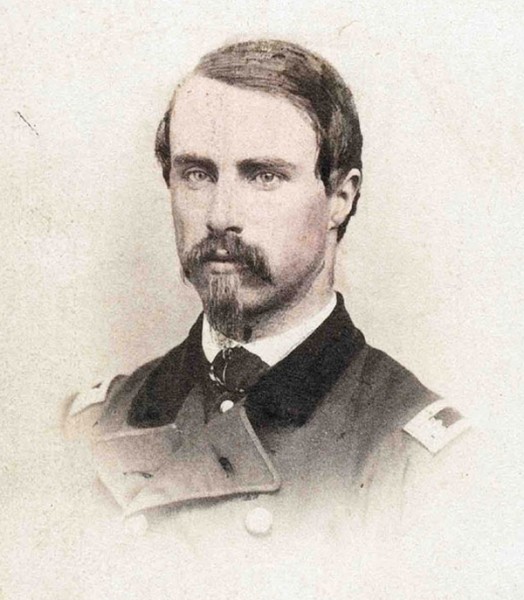

A heated argument ensued between Colonel Irwin and Major Thomas Hyde. Hyde was 21-years-old, a native of Bath; the 7th Maine, his regiment—he felt a deep responsibility to his boys. The proposed mission was absurd, certain suicide. But Colonel Irwin commanded the entire brigade; he ranked above regimental leader Hyde.

“Colonel,” protested Major Hyde, “I have seen a large force of Rebels go in there, I should think two brigades.”

Irwin insisted, saying, “Are you afraid to go, sir?”

So go they did: 181 men lit off for the farm. Hyde led his men down into and up out of the notorious sunken road that would come to be known as the Bloody Lane. Hyde would recall that it was “so filled with the dead and wounded of the enemy that my horse had to step on them to get over.”

Once they’d cleared this grisly impediment, Hyde ordered his men to charge up the gently sloping ground at the edge of the Piper Farm. At this point, the Maine boys encountered their first fire from Rebels hiding behind a stone wall that ran along a portion of the Hagerstown Pike.

As Hyde crested the ridge on horseback, he saw to his horror what awaited his Maine boys on the Piper Farm. The place was crawling with Rebels: Texans, Georgians, Louisianans, and Mississippians—too many to estimate in the moment, certainly enough to dwarf the 7th Maine’s paltry number

Hyde shifted course, leading his men into an apple orchard, a place that might offer some cover. But the orchard turned out to be fenced in on three sides, a fatal trap. The Maine boys fell under fire from muskets and canister. They were driven back against the far fence. William Crosby of the 7th Maine would later write: “bullets, men, and apples were dropping on all sides.”

Major Hyde’s horse was shot in the hip and mouth, and the wounded animal couldn’t jump the fence. Hyde dismounted, and led his boys in a wild dash to safety.

The 7th Maine retreated back to the same spot from which they’d set out. Only now the regiment was down many men: 12 were dead, 63 injured (another 13 of whom would soon die), and 20 were missing. Major Hyde and the survivors lay on the ground, sobbing like children.

Why this senseless sortie? It turned out that Col. Irwin was driven by nothing more than the “inspiration of John Barleycorn,” as Major Hyde put it. That’s right: late in the day, a drunken commander had sent the Maine boys to their demise, and for nothing.

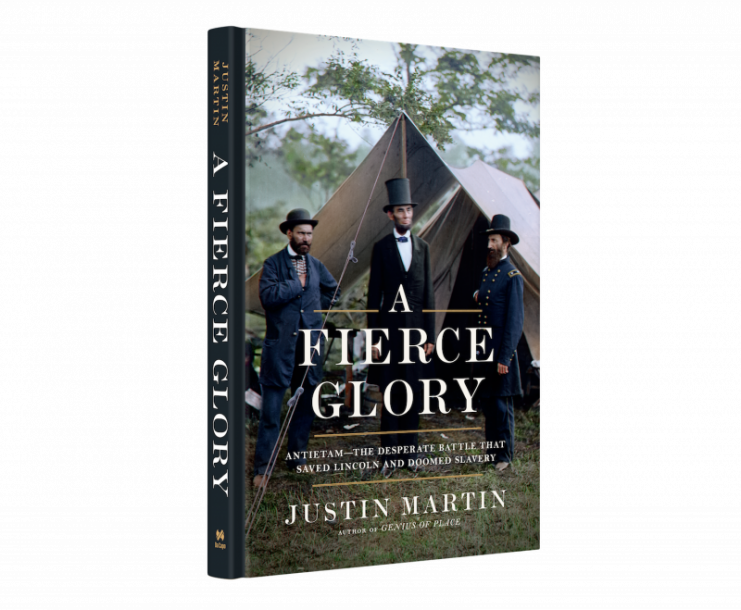

This is one in a series of posts, as guest blogger Justin Martin counts down to the September 17 anniversary of Antietam, still America’s bloodiest day. Martin’s posts will feature little-known episodes he learned about while researching his new book, A Fierce Glory: Antietam—The Desperate Battle That Saved Lincoln and Doomed Slavery (Da Capo Press).

You can order the book here.

Read another article from us – 2 Hour Break At Antietam – Suddenly Both Sides Stopped Fighting

Justin Martin will continue to share some special and insightful stories about the Battle of Antietam throughout the week. Please stop by tomorrow to catch the next installment.