“One night I was sitting looking at a blank, unpainted wall. To pass the time I wrote four pages of dialogue between a second lieutenant and an Army mule”

Mules have a long history with warfare. Hardy and stubborn yet loyal to those who earn their trust, mules have served as pack animals for army supply trains since mankind first learned how to breed them.

As societies advanced, it wasn’t long before the mules in early civilization’s armies had two legs instead of four. Roman Legionnaires started calling themselves Marius’s Mules after the military reforms instituted by Gaius Marius required the troops to carry more supplies to speed up its marches.

Ever since, army men and army mules have been synonymous to many in and out of the service.

Rarely have the four-legged versions been able to talk. Yet sometime before Mister Ed hit the screens, one young Army captain wrote of a talking mule.

David Stern III, born in 1909, joined the war effort in 1943. As he described it: “I had been publishing a couple of newspapers. I told this to the classification interviewer, who dutifully recorded my civilian background on a large card. They say the Army always finds the job to fit the man. I was assigned as an assistant on a garbage truck.”

While serving, Stern found himself an officer stationed in Hawaii working for an Army newspaper. Far from combat, Stern, like many soldiers not in the process of fighting for their lives, got bored.

In Sterns own words, “One night I was sitting looking at a blank, unpainted wall. To pass the time I wrote four pages of dialogue between a second lieutenant and an Army mule. I had no intention of writing more. But that little runt of a mule kept bothering me. With memories of OCS (Officer Candidate School) fresh in my mind, I thought I might rid myself of the creature by shipping him off to become a second lieutenant. Francis outwitted me. He refused to go.”

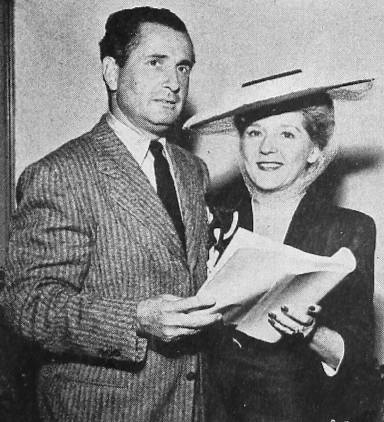

Writing under a pen name, Stern submitted several stories to Esquire magazine about a young second lieutenant fighting in the Pacific and befriending a talking mule. After the war, he combined the stories into a novel aptly called Francis, about the lieutenant and his talking mule companion that only he could hear.

A few years later, Stern managed to get the stories made into a series of movies by the future director of Mister Ed himself, Arthur Lubin.

The movies proved a comedic success. An early precursor to the Golden Globe, the first Annual Patsy Award was awarded to Francis in the American Humane Association category in 1950. He won second place in 1952, 1954, 1955, and 1956. He came third in 1957 and won the award again in 1953.

Seven movies in total were made chronicling the adventures of the Army mule Francis and his human companion through their various escapades. Though Mister Ed would eventually eclipse the duo, their effect on both post-war morale and Stern’s career cannot be overlooked.

In literature, comic books, and the silver screen, Stern’s creation entertained people in troubled times.

The adventures of Francis and his human compatriot started as the bored scribbling of an American Army officer far from home and farther from the front. With his wit and knowledge, he wove a tale of two Army mules cooperating to lead a life of adventure and fulfillment.

Read another story from us: The Horses, Mules and Donkeys That Fought in World War One

Though Stern never saw combat in Burma like his characters, his works provided entertainment following the troubling times of the early Cold War. Whether man or animal, the mules of the Army would do their duty, and, whether talking or not, their tales would live on in story and screen thanks to the like of Stern.