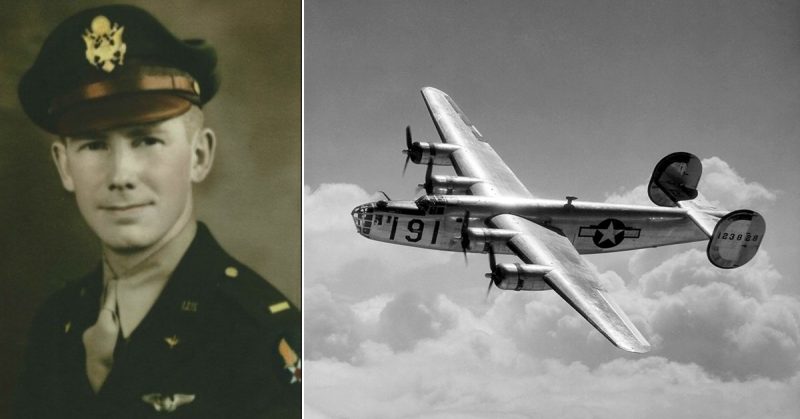

During my twelve years of association with the National Museum of the Mighty Eighth Air Force in Pooler, Georgia, I have had the opportunity to meet many WWII Eighth Air Force veterans. One of the most interesting personalities was a country boy from Toccoa, Georgia, who was drafted out of college in February of 1943, and graduated from the United States Army Air Force’s officer candidate program as a navigator in April of 1944.

This man, Farish C. “Hap” Chandler went on to fly 35 missions with the 489th and 491st Bomb Groups of the Eighth Air Force during WWII, and later, 50 night-intruder missions in B-26 medium bombers in Korea. Hap retired from the USAF in 1970 as a Lt. Colonel and had a successful civilian career as a contract administrator.

He also became a well-known leader of veterans affairs in the Atlanta, Georgia, area. His involvement in the veteran community led him to become a founding member, on the Board of Trustees, of what is now the National Museum of the Mighty Eighth Air Force.

It was my pleasure to talk with Hap when he came to Pooler to attend museum board meetings.

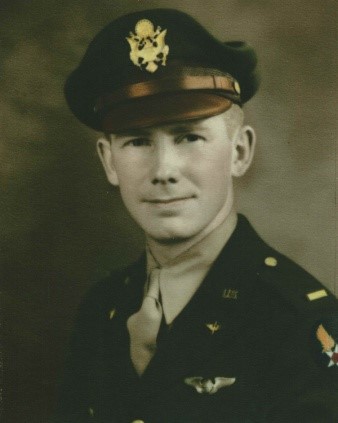

Our friendship developed over the years, and finally, when his health was failing in 2015, at age 94, I was honored when he called to say that he wanted me to help him complete his memoir in the time he had left on earth. During the following months we talked on an almost daily basis as I read material that he, and others, had prepared over the years – mostly regarding his time in the military.

Developing new material and combining it with what had been put together previously was a challenge. The revised manuscript was e-mailed, by chapter, to Hap’s family, who read the material to him for his final approval. We arranged for a publisher to put Hap’s work into book form and he approved the final manuscript in September of 2016.

Hap didn’t live to hold a copy of the memoir in his hands and present it to his family as he had hoped to do, and he and I did not get to do a book signing together as he had planned, but when he made his last flight on October 10, 2016, he knew that his words had been recorded to mark forever his place in the history of his family and our country.

During more than a decade of listening to Eighth Air Force veterans describe the anxiety of young men fighting a war with the dichotomy of facing death during the day and sleeping in warm beds after drinking beer with comrades at night, each veteran had a unique view of how that situation had affected him.

Hap often spoke of the stress and fear he felt from the minute he was awakened by a shouting messenger on days he would be flying a mission and how the many challenges of the hours that followed would at times become overwhelming for him.

In the months since Hap’s passing I have been compelled, on several occasions, to look through my copy of his memoir. Several of the pages have always stood out to me because of the powerful emotions they send to the reader, describing, in Hap’s own words, a “mission day” for a bomber crew in the 8th Air Force in late 1944. What follows are Haps own words:

“We would be awakened around 4:00 AM and report to the mess hall for breakfast at 5:00 AM, followed by the mission briefing at 6:00 AM. The general Group briefing for all flight crew was often followed by a second briefing for pilots and navigators. After the briefings, we were driven in the backs of trucks to the flight line, where we would begin our preparations for the mission based upon our role in the crew.

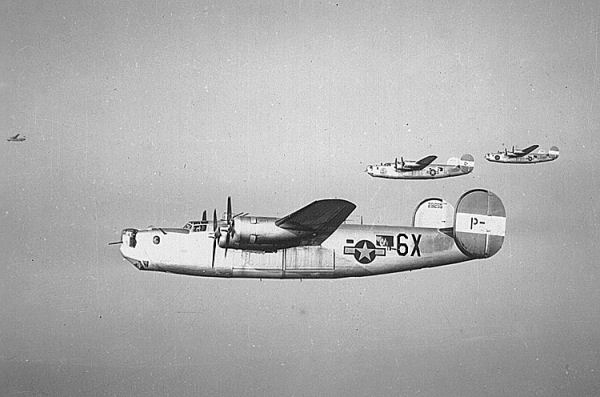

There was a signal, usually a flare fired from the control tower, to start our engines, and then another flare would signal that we should start to taxi to the takeoff runway. More often than not there would be fog or cloud cover over the base. (Clouds or fog in England would not cancel a mission – clouds over the target would!) Each takeoff of a mission was scary, regardless of the weather. The B-24s were overloaded with four tons of bombs and 2,600 gallons of highly flammable aviation gasoline!

After turning to face the runway, the pilots (who were under pressure from the long line of airplanes behind them to get down the runway as soon as possible) stood on the brakes and firewalled the throttles of the four Pratt & Whitney engines. The airplane began vibrating. When the engines were at maximum power, the pilots released the brakes and we began to roll down the runway, which was only 5,600 feet long, 1,500 feet shorter than the minimum length standards in stateside bases.

We were instructed to be only 30 seconds behind the B-24 in front of us, and we could expect that there would be another B-24 30 seconds behind us. At this point, everyone was holding their breath. At what appeared to be almost the end of the runway the nose wheel lifted off the ground, followed by the two main gear wheels under the wings. This was a touchy moment because when we reached 100 feet the pilot had to lower the nose in order to pick up speed to 160 miles per hour, which was necessary to keep us in the air.

We all had lost friends in airplanes that failed for some reason during the liftoff from the runway, causing a fiery crash at the end of the runway that very seldom left survivors. The pilots worked to attain a climb rate of 300 feet per minute. Many times the cloud cover or fog over our base would be only several hundred feet off the ground. Under those conditions, we would enter the clouds, or fog, without being able to see the B-24s in front of and behind us.

After the challenge of the takeoff, the pilots had to fly the airplane using only instruments for guidance and hope that there was not another B-24 near us in the cloud or fog that had somehow changed their position after takeoff. On several occasions during my tour, we were frightened beyond belief when we would witness a bright flash and rumble that indicated 20 of our friends had just perished when two bombers collided in the heavy clouds.

At no specific altitude, we would emerge from the mist – sometimes only temporarily – and then finally to the most welcome sight of all, bright sunshine! When we finally did emerge from the top cover, we immediately searched the skies in order to determine our location with regard to our group’s aircraft. We would also see B-24s from surrounding bases emerging from the clouds and forming their formations.

Each group had a beacon signal coming from their control tower and each circled that beacon’s signal forming the Group’s four Squadrons into the formation that was briefed before takeoff. We all gathered on the multi-colored Group Forming Ship. There would be three levels of our Group formation, by squadron: Lead, High and Low, broken out into elements of three aircraft in a “V” formation.

As all of this was occurring, I would leave my takeoff station on the flight deck and move forward to the nose section of the B-24. This involved crawling through a tunnel and getting past the nose wheel while dragging a bag full of my navigator’s gear. Once in the nose, I set up my station or, when flying lead, as I did later in the war, climbed into the nose turret for a good view of the territory in front of the formation. All of this was an exercise in gymnastics which got more difficult as the air became thinner.

After our squadron and the group were formed in proper order we would then form up with the nearby Groups, using the same formation of Lead, High and Low Groups forming a Wing. When this amazing organization was completed we would turn and head for the continent. As we crossed the North Sea our formations would often, in 1945, be 100 miles long. A marvel of power and accomplishment!

The first leg of our journey passed over the North Sea. I developed a fear during my time in the 8th Air Force of coming down in the North Sea, a fear equal to my fear of the German Luftwaffe and flak gunners. The B-24 had a terrible reputation for breaking apart when it hit the water, and leaving few survivors. Because of its high wing, the fuselage almost always collapsed, making survival chances poor, at best.

Despite the relief that we would not have to ditch, it was hard to breathe a sigh of relief as we approached the coast of Holland due to the Kammelhuber Line (an intense wall of German anti-aircraft artillery that stretched from Norway to Switzerland).

Further, because the Germans knew we were coming they would be assembling their fighter aircraft, including the new Messerschmitt-262 jets, over Dummer Lake. We felt fairly safe from the Luftwaffe as we were surrounded by hundreds of P-51 fighters escorting us all the way to the target.

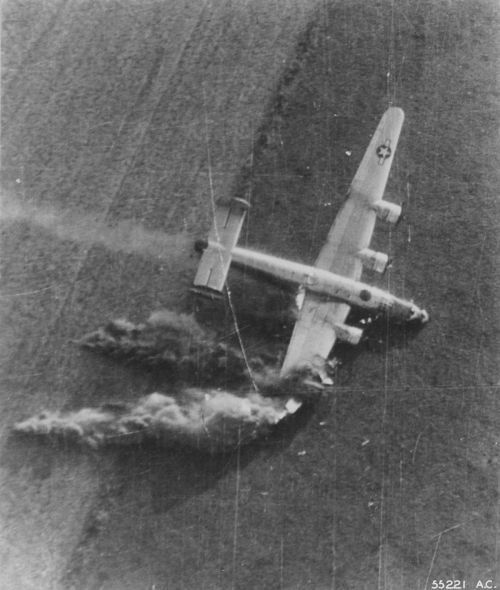

There was nothing, however, we could do about flak. You just hoped you were not on the receiving end of one of the thousands of shells being hurled into the sky as we flew towards our target. Flak over the targets was the most intense. Then, on the trip home we would have to, once more, pass over the Kammelhuber Line, many times with the airplane having already suffered damage during the mission.

One time we returned with only two functioning engines. After crossing the Dutch coast, we would begin our letdown from bombing altitude, eventually arriving at 10,000 feet, where we no longer needed our oxygen masks. Removing the masks was always a welcome moment. I liked to celebrate by taking the Hershey bar from my flight suit that was there for just this occasion and tasting the pure joy of the chocolate.

Then came the second trip over the North Sea before arriving over our base and having to do the letdown through the clouds for a landing, a task that was often almost as difficult as the takeoff. We dropped down through the clouds and, hopefully, lined up on the runway. The tires squealed as we touched the tarmac. As the brakes and flaps slowed the airplane, we reached the end of the runway and taxied to our hardstand, where the ground crew guided us into our parking place.

There was much to do while flying a mission, and it was easy to suppress anxiety, but when we came home my fears began to surface and had to be dealt with in the hours that followed. Even an “easy” mission was a very tough day! After the entire crew had climbed out of the airplane, we were taken by truck to post-mission interrogation. The intelligence officers repeated “time, place, altitude” as we attempted to reconstruct incidents occurring during the mission.

When we were done with the interrogation, the mission was complete. We returned, exhausted, to our quarters and welcomed the luxury of our warm bunks. That was the story of a day in the life of a bomber crew in the 8th Air Force in late 1944.”

God bless Hap Chandler, and may he rest in peace.